Where is Amarna?

(El) Amarna is a city in Middle Egypt between Cairo and Luxor. The archaeological site near the modern city, called Tell El-Amarna (The hill at El-Amarna) is the remains of the ancient Egyptian capital Akhetaten which thrived for a brief period in the 1300s BCE. It was the new capital of the famous religious reformer (or “heretic king,” depending on your stance), Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenophis/Amenhotep/Amenhotpe IV, 1350-1334 BCE) and his father Amenophis/Amenhotep/Amenhotpe III (1386-49 BCE). Akhenaten’s wife was the beautiful Nefertiti. Akhetaten was the Washington or Berlin of its era, involved in international diplomacy far beyond the borders of Ancient Egypt, especially with weaker kingdoms in the Levant that were vassals of powerful Egypt. The city came to an end within a dozen years after the death of Akhenaten in 1334 or so, although his successors Smenkhkareand Tutankhamun (“King Tut”) lived there for a short time before returning the capital to Luxor.

The building where the tablets were housed lay behind the Pharaoh’s palace and was called “the place of the letters of the Pharaoh.” In addition to this relatively small library of “foreign” documents, the archive housed a larger number of Egyptian texts.

Description

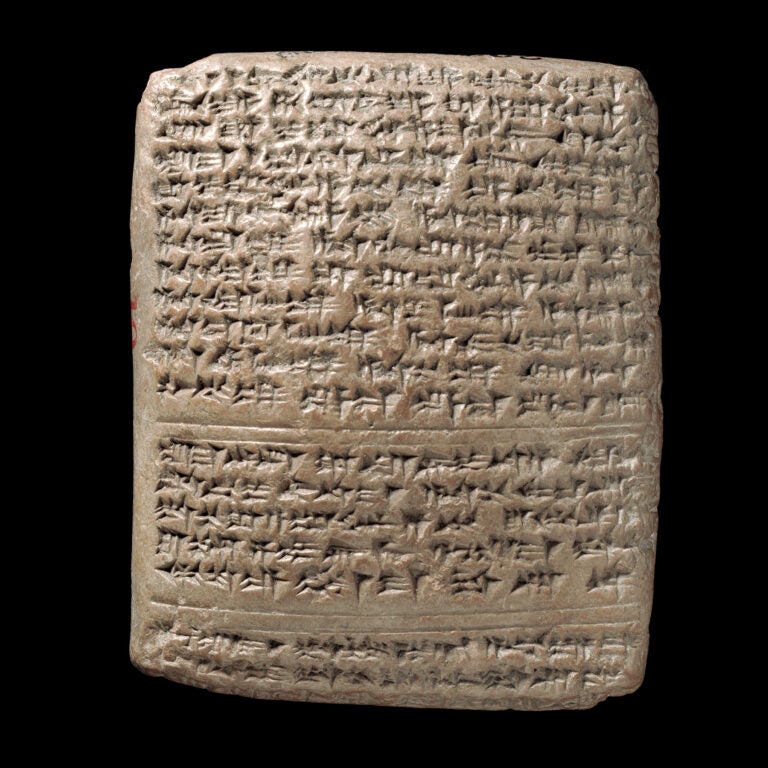

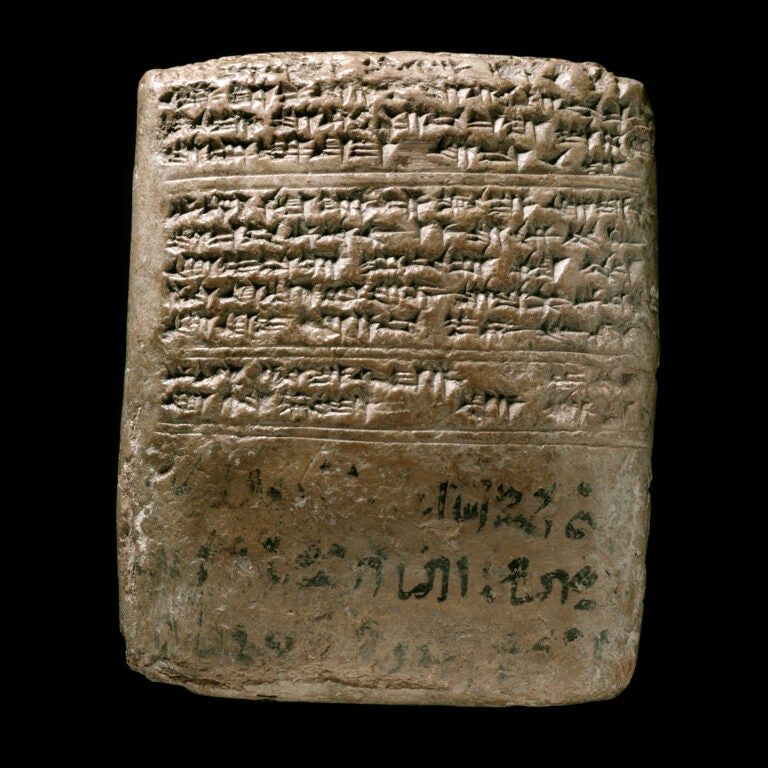

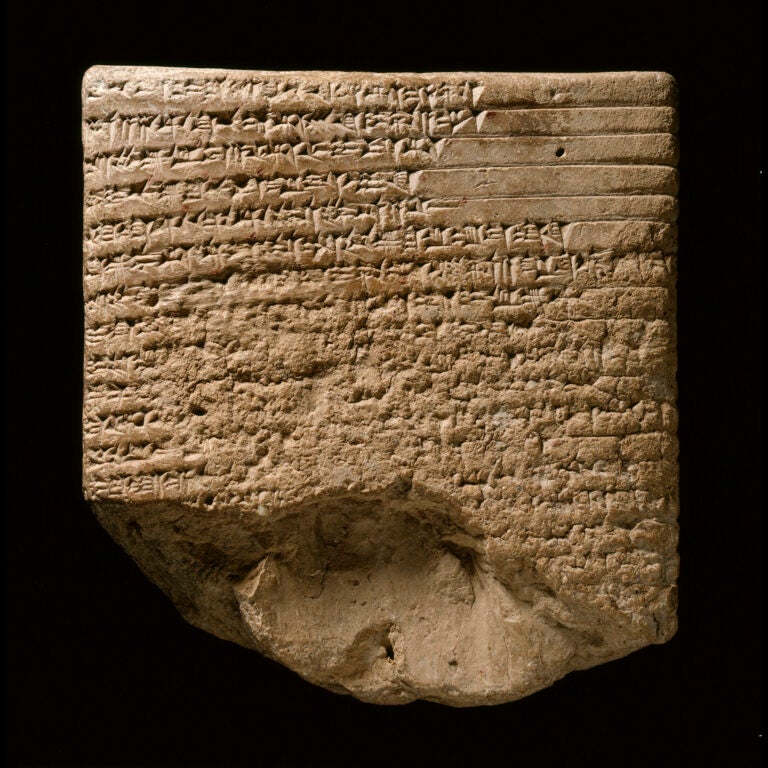

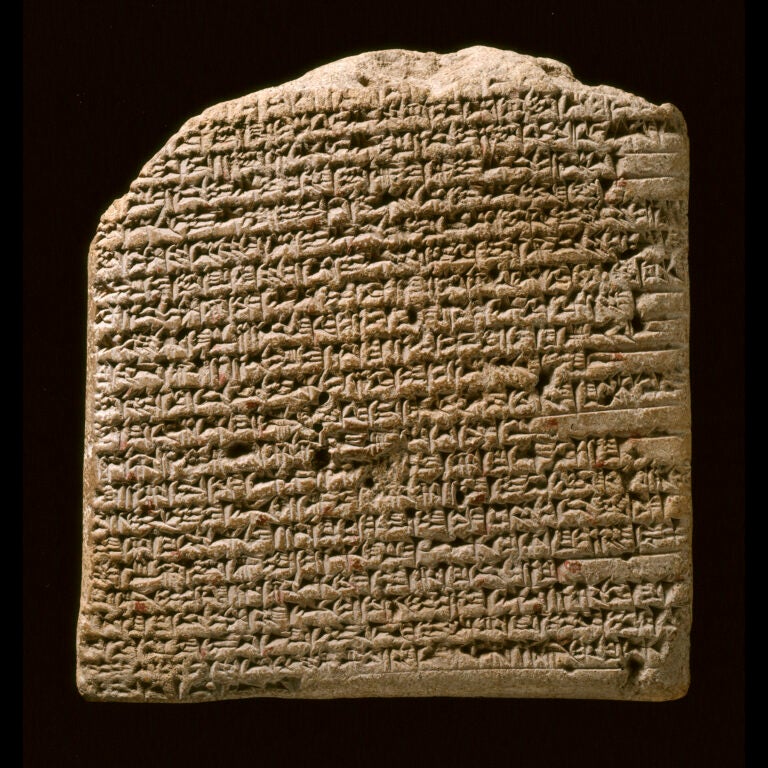

The clay tablets are mainly diplomatic letters (with a few myths and epics) written in cuneiform script (wedge prints made in wet clay then baked), often covering both sides of a tablet for efficiency. From the side view, they often resemble fat hamburger patties! They were originally part of a court archival office.

The El-Amarna tablets were written during a very brief period historically: the second half of the fourteenth century BCE (1400-1300 BCE), the “New Kingdom” period in Ancient Egypt and late Bronze Age in Palestine. The actual duration of the correspondence is likely not much more than 25 years total. The tablets take us intimately into one of the most popularly recognized periods in ancient Egypt with connections to Nefertiti and her husband Akhenaten, sometimes credited with being one of the first monotheists.

They first came to light In 1887, when local Egyptian peasants found a few tablets buried in the ruins of the Akhetaten palace complex and sold them to antiquities dealers. Later excavations recovered the rest, beginning with the work of English Egyptologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie in 1891-92.

382 tablets (350 of which were letters), now scattered among various museums but mainly found in:

- the British Museum in London

- the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

- the Vorderasiatishes Museum in Berlin

The tablets found in El-Amarna are mostly “letters received” from abroad, not letters written in Egypt. Letters from abroad came from other kings of Babylonia, Assyria, Hatti (Hittites in Eastern Asia Minor), Mittani (Hurrian, north of Assyria), and Cyprus (Alashiya), but the majority come from vassal rulers in Syria-Palestine (Canaan, Lebanon, Ugarit, and the eastern Mediterranean coastal lands). Letters from Egypt were written by scribes of the pharaohs and were sent out of Egypt and presumably lie in the ruins of the cities where they were received. Some draft letters by the pharaohs, however, stayed in Akhetaten. We can also assume that most copies of vital correspondence were archived locally in the Egyptian language, rather than in their Akkadian translations.

The topics they deal with include:

- Exchanges of gifts between rulers (e.g., fancy furniture, gold, linen, etc.)

- Diplomatic marriages (one letter from a Babylonian king asked for proof that his sister, one of Pharaoh’s earlier wives, is still alive before sending the Pharaoh his daughter as a new wife!)

- News about events in distant cities: Byblos, Tyre, etc.

- Requests for grain and other foodstuffs, lumber, ships, military aid, etc.

- Vassals’ concerns about the rising military threat of the Hittites on the northern borders of Egyptian influence and concern from Jerusalem and Gezer, too, about the military threat from the ‘Apiru.

- A few contain myths and legends.

Unexpectedly, when the tablets were discovered, they were written not in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, but in a foreign language, Akkadian, the language of Babylonia and the diplomatic lingua franca of the day used between different kingdoms to communicate. Two tablets are in Hittite (an Indo-European language) and one in Hurrian, spoken in the Mitanni kingdom north of Assyria.

Scholars of West Semitic languages are interested in the tablets because the Akkadian on the tablets sent from Canaan is heavily mixed with Canaanite dialects: scribes writing in “Akkadian as a Second Language”! One of the main translators of the tablets, William Moran, who made a vital breakthrough in recognizing the mixing in 1950, wondered whether this pidgin Akkadian “should be called Babylonian at all,” since it seems to be Babylonian vocabulary strung together according to West-Semitic grammar rules. Thus, the language on these tablets gives us insight into West Semitic languages of the second millennium BCE.

WSRP was given permission by the British Museum to photograph their entire Amarna collection beginning in 1999. The Near Eastern Museum (Vorderasiatisches Museum) in Berlin also allowed WSRP to photograph part of their collection of tablets, 53 of which were done in 2005. Moran calls the tablets “a kind of preface to biblical history,” and thus of import to scholars of West Semitic languages and history. They provide a vital source in helping linguists reconstruct older forms of West Semitic, including Proto-Hebrew.

The letters from Jerusalem (Urusalim) from ‘Abdi-Heba (EA 285-290) are full of dire news of invasions and desertions by local mayors to the Hapiru/’Apiru–“Lost are the lands of the king”–and imploring the king of Egypt for military rescue. “As the King (of Egypt) has placed his name in Jerusalem forever, he cannot abandon it!” (EA 287)

While conservative scholars immediately identified these Hapiru with the Hebrews, whose conquest of Canaan is mentioned in the Bible (e.g., the book of Joshua), other scholars have doubted the connection, since the term was used widely in the Ancient Near East for foreign marauders or mercenaries, some who were even part of the king of Babylon’s army. Carol Redmount describes the Apiru/Habiru as “a loosely defined, inferior social class composed of shifting and shifty population elements without secure ties to settled communities,” described as “outlaws, mercenaries, and slaves” in ancient texts.

A number of names of Canaanite (Kinahni) cities come up in the Tablets: Ashkelon (Asqaluna), Gaza (Hazzatu), Gezer (Gazru), Hazor (Hasura), Joppa (Yapu), Lachish (Lakisa), Megiddo (Magidda), Shunem (Sunama), and others.

Here is an example from from Moran’s translation of EA 213 “Preparations under way” from the British Museum:

“Say to the king, my lord, my Sun, my god: Message of Zitriyara, your servant, the dirt under your feet, and the mire you tread on. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, my Sun, my god, 7 times and 7 times, both on the stomach and on the back. I have heard the message of the king, my lord, my Sun, my god, to his servant. I herewith make the preparations in accordance with the command of the king, my lord, my Sun, my god.”

EA 23: Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman and Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research. Courtesy British Museum.

EA 357: Photograph by Bruce Zuckerman and Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research. Courtesy British Museum.

Article Categories

Non-Biblical Ancient Texts Relating to the Biblical World: Non-biblical inscriptions and documents from ancient times that improve our understanding of the world of the Bible.

Biblical Manuscripts: Images and commentary on ancient and medieval copies of the Bible.

Dead Sea Scrolls: Images and commentary on selected Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts.

USC Archaeology Research Center: Images of artifacts from the teaching collection of the University of Southern California.