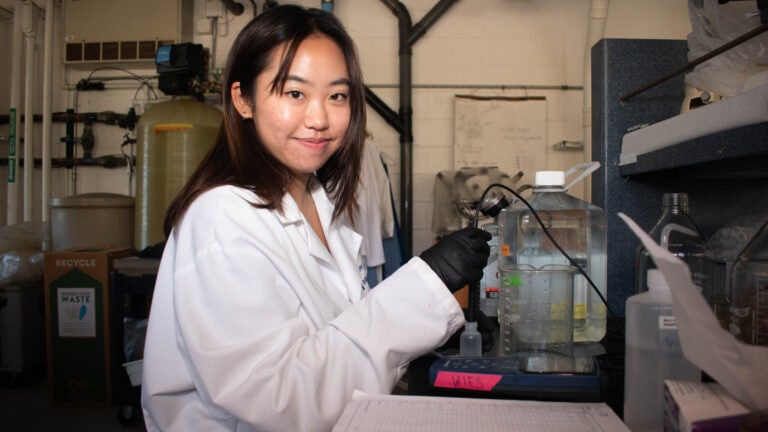

2023 Zinsmeyer Summer Research Program student Esther Lim helps to illuminate how accelerated weathering of limestone, an ocean carbon sequestration method, may affect marine ecosystems. (Jason Goode/USC Wrigley Institute)

Exploring the potential for carbon sequestration through ocean alkalinity enhancement and the accelerated weathering of limestone

Hauling liters of seawater up steep hills. Calibrating and recalibrating finicky equipment. Standing rooted in front of a machine for entire work days, running the same test on dozens upon dozens of samples. A lot of the work I’ve done might seem like the most menial of tasks, but I’ve never felt so much purpose in my undergraduate career as I have this past summer.

I’m Esther Lim, a rising senior at USC, majoring in environmental studies with a minor in cinematic arts. I’ve had the privilege of participating in the Zinsmeyer Summer Research Program at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island, working with my mentor and PhD student Rucha Wani in Dr. Will Berelson’s lab on carbon sequestration.

This is actually my third time at the Wrigley Marine Science Center within the past school year, and looking back, it seems like each trip to the island coincided with a different stage in my personal career journey. My first was through an environmental studies (ENST) cohort trip in the fall, where I got to know fellow environmental studies students through a weekend of exploring the island, participating in fun activities like snorkeling and hiking, and getting excited about the different ways to get involved with the Wrigley Institute.

The second time was to close out the Spring Break Climate Careers trip, a week-long program of tours and panels with environmental industry professionals. While it was incredible to learn so much about all the possible careers in sustainability, I couldn’t help but feel a bit of panic at the realization that my junior year was coming to a close, and I still didn’t exactly know what I wanted to do with my major for a living.

This led me to my current time on Catalina Island. I happened across the Zinsmeyer Summer Research Program application sharing a research position specifically for those interested in work that would contribute to protecting our planet. Having no previous experience in research and academia, but very interested in saving the world from climate change, I applied and found myself headed back to the Wrigley Institute for a 10 week long project on carbon sequestration.

Carbon sequestration, also known as carbon capture and storage, actively addresses the ever-growing threat of climate change by capturing the excess carbon dioxide warming our atmosphere and storing it away in “sinks”. The method of sequestration we’ve been working with is called ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE), utilizing the ocean, the largest natural sink, to store carbon. There are also different methods of OAE, but Calcarea, a carbon sequestration start-up partnered with the Berelson lab, utilizes the accelerated weathering of limestone (AWL) to achieve OAE. While carbon dioxide reacting with water normally results in carbonic acid and ocean acidification, adding calcium carbonate, more commonly known as limestone, essentially neutralizes this acid into bicarbonate and results in a highly alkaline effluent product. It’s a lot of chemistry, but Rucha best explained this to me as “TUMS for the ocean.”

Immense potential for sequestration and fighting climate change lie in ocean alkalinity enhancement and the accelerated weathering of limestone. However, we haven’t seen any large-scale deployment of these strategies because of the equally immense biogeochemical uncertainties that have yet to be figured out. How does the release of this effluent product affect marine life? Does the carbon stay sequestered? What amounts and what concentrations of effluent are best and/or safest? We need answers to these questions, and this is where our research comes in.

My project in particular examines the partitioning of carbon between two different batches of the Calcarea water – whether it stays dissolved in water as bicarbonate, precipitates out into particulate matter, or if it outgasses and returns to atmospheric carbon dioxide. Comparing the two batches of Calcarea water also allows us to study the variation in the reactor’s effluent product. We do this by collecting seawater samples off of the Wrigley dock, adding various concentrations of Calcarea water to the seawater bottles, letting them incubate, and sampling and filtering them to run various tests, including alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, DNA, and of course, their carbon content.

It’s admittedly a lot of work, but joining the program opened my eyes to the world of academia, and for lack of a better word, the “science” side of environmental studies. It’s been thrilling to find myself behind the scenes of the science that we base our policy work off of, the material I’d spent years studying, and to literally be part of advancing that science with my own hands! Being at the Wrigley Institute and around other people equally curious, excited, and passionate about their work has also been incredibly inspiring, and also just so much fun.

Not only has it been sweet to see the island change over the seasons – from the hyper-green hillsides that sprung from the extreme rainfall over the winter, to seeing baby quails hatch and chase around their parents in the earlier summer months – I feel proud and grateful observing my own development in just a year as I was able to explore my interests and passions within the environmental field.

I can’t say with certainty that research is the answer I’ve been looking for to my career woes and search for meaning. However, I will say that I’m very excited to continue working with Rucha and the Berelson lab through the rest of my senior year. I’m beyond grateful for the opportunity to have participated in this program, and look forward to continuing on in this field that is the effort of so many people working to save the world.