Casting cancer as a ‘war’ or ‘battle’ may harm health, study finds

Cancer is often cast as a “battle” or a “war” that should be fought and won to motivate patients to overcome the disease, or encourage people to make healthy choices that could prevent it.

However, psychologists at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Queen’s University have found that the battle and war metaphors for cancer may have the opposite effect.

“We found strong evidence that battle metaphors and war metaphors reduce your willingness to engage in these ‘soft’ prevention behaviors,” said Norbert Schwarz, Provost Professor of Psychology and Marketing at USC Dornsife.

Those soft preventive measures include healthy activities and lifestyle changes.

“It’s a mindset,” Schwarz added. “Doing the preventive stuff like eating healthy and sleeping enough don’t sound very appealing. People think, ‘That’s not how you beat bad odds. To beat the odds, you bring out the big weapons. You don’t eat salad.’”

The study is forthcoming in the journal Health Communication.

Schwarz and study co-author David Hauser of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, have been studying the war and battle metaphors of cancer in recent years because they noticed that the rhetoric seemed very common.

For this latest paper, they conducted four studies with about 1,000 people. Participants were given a story about a fictional cancer patient that either included words that cast cancer as a “journey” or words referring to the cancer as a “battle” or a “war.”

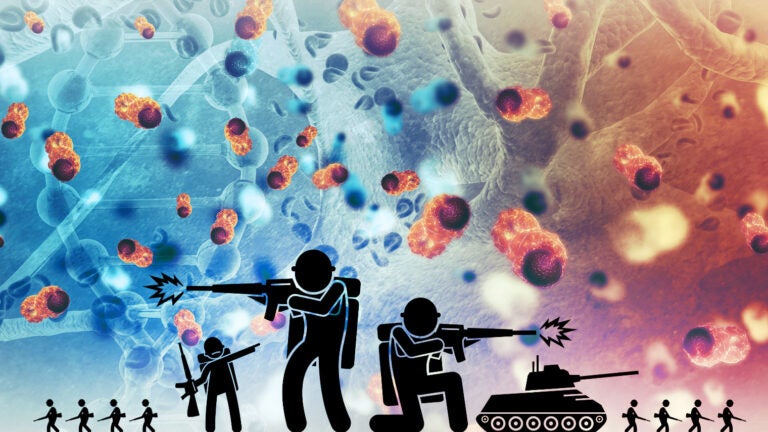

“Fight” and “battle” are among the top 10 verbs to appear within four words of the word “cancer,” and many organizations use these terms when fundraising for the disease. (Composite: Dennis Lan. Image source: iStock.)

Participants who received the story with war-like terms believed that the fictional patient’s treatment would be difficult. They also were more fatalistic about cancer treatment, perceiving the disease as something they might be destined to get. They also did not become more vigilant about prevention.

“Reading about a person’s ‘battle’ with cancer increased participants’ fatalistic beliefs about cancer and its controllability,” Hauser said. “This is especially concerning because high cancer fatalism is associated with numerous negative health behaviors.”

Schwarz and Hauser had thought that because battles involve vigilance, perhaps hearing the battle metaphor would motivate people to regularly check for the warning signs of cancer and adopt a healthier lifestyle that could possibly prevent the disease.

Instead, the idea of the war on cancer “increased fatalistic beliefs about prevention,” they wrote.

“People have thoughts like ‘I feel meant to have cancer,’” or they have a mindset of ‘if you get cancer, you know it’s very hard because you have to battle it,’” said Schwarz.

Schwarz and Hauser reported that prior research has found that “fight” and “battle” are among the top 10 verbs to appear within four words of the word “cancer.”

Schwarz noted that many cancer research fundraising organizations use these terms, and they seem to motivate people to donate funds.

“The metaphors we use to frame health and disease have the power to influence public health in beneficial or harmful ways,” Schwarz and Hauser wrote. “It is therefore important to investigate the inferences that metaphors promote before entering them into public discourse or making them a central theme in health communications.”