#LastSeen: Searching for forgotten photographs of Nazi deportations

Bundled up against the winter chill, the two little girls gaze out of the black-and-white photograph with contrasting expressions. The younger child at right offers a rueful smile. But it is the solemn little girl on the left, wearing a fur scarf and hat, her mournful gaze directed straight at the camera, who holds our attention. Her beauty and sadness alone are enough to haunt our dreams. But when you add the Stars of David stitched to both children’s coats, branding them as Jewish under Nazi rule, and then note the photograph’s date — Nov. 11, 1941 — the image becomes unforgettable.

The two children shown in the photo, along with nearly 1,000 other German Jews, were deported from Munich on Nov. 20, 1941 — then murdered days later in the Kovno Ghetto of Nazi-occupied Lithuania.

Through the study of more photographs depicting Nazi deportations, like this rare image — one of only a few hundred known to exist worldwide — participants in a groundbreaking new initiative hope to improve their understanding of these events and piece together the untold stories of both victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust. For assistance, they’re turning to the public.

“Photographs of these tragic events are rare, but with the public’s help, we hope more, currently unknown, images will be discovered — not only in archives and museums, but also in private attics and basements,” says Wolf Gruner, founding director of the Center for Advanced Genocide Research (CAGR) at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Shapell-Guerin Chair of Jewish Studies and professor of history.

CAGR is currently the only institution outside Germany supporting the #LastSeen Project — Pictures of Nazi Deportations, which was launched late last year. Funded by the German government, its goal is to gather, analyze and digitally publish pictures of Nazi mass deportations of Jews, Romani people and people with disabilities from the German Reich between 1938 and 1945.

“Who knows how many photographs like the one of the two little girls above are lying forgotten in the homes of survivors and their descendants?” says Gruner. “As the only North American organization involved in the project, we need the English-speaking public’s help to search for these images, so we can analyze them to build a more detailed picture of what happened during Nazi deportations.”

The project is a collaboration between the Arolsen Archives, the City of Munich Archives, the Center for Research on Antisemitism at the Technical University Berlin, the House of the Wannsee Conference memorial site, and CAGR.

“Usually, we see photographs of deportations as just a group of people dragged through a city by uniformed perpetrators,” says Gruner. “But with this project, we want to illuminate who these people were and what happened to them. Who were the victims, the perpetrators and the onlookers?”

Gruner says the first step to answering these questions is to gather existing photographs. The second is to find more images. The third is to analyze them and uncover their stories.

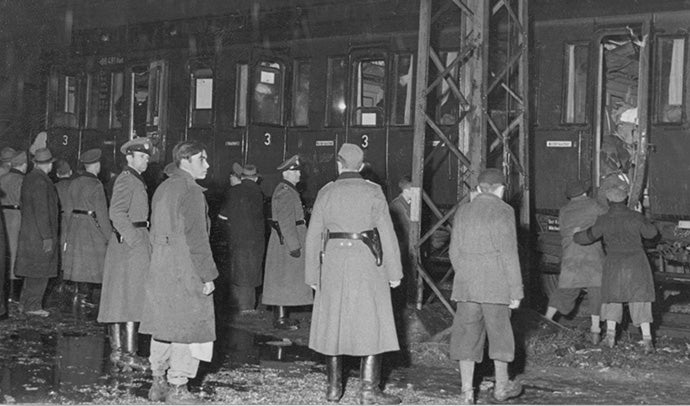

While not a single photograph has been found so far of the Nazi deportation of more than 50,000 Jewish residents of Berlin, Munich is different. The City of Munich Archives hold 14, including this one showing the first deportation — one of the few to take place at night — from Munich to the Kovno Ghetto in Lithuania on Nov. 20, 1941. (Photo: Courtesy of the City of Munich Archives.)

First-of-its kind project

“Photos of Nazi mass deportations have never before been brought together, made available as a digital collection, and analyzed collectively in any systematic way,” says Alina Bothe, #LastSeen project manager in Berlin. “Nor has there been a concerted effort to search for more photos.”

These pictures tell many stories — of the deportees, the perpetrators and the spectators, says Bothe, who invites the public to help by finding photographs in museums, archives, private attics, basements, or even dusty photo albums.

In its first phase, the #LastSeen Project will cover Germany before branching out to also incorporate other territories once occupied by Nazi Germany, such as Austria, France and Poland. These stages include intensive research in archives and public outreach.

The project is also developing a digital platform to publish the pictures with information about their origins as well as the people and locations shown in the images.

Part of the project includes building educational tools on how to find, analyze and understand photos of Nazi deportations.

The project has already yielded exciting results.

At its launch, it was thought that pictures of mass deportations existed from approximately 30 German cities and towns.

“A few months into the project, after contacting more than 1,500 German archives, we have already identified pictures from more than 60 locations in Germany — a total of 525 images,” Gruner says. “Even for many of the places that were already known, we have discovered more photos than we previously knew existed.”

Project researchers identified two photos in the archives of the Center for Jewish Studies in New York, showing a deportation from Bad Homburg, Germany. “The German city and its archive had no idea that the Nazi deportation in their town had even been photographed,” Gruner says.

Gruner made an unexpected discovery of his own in the Visual History Archive of the USC Shoah Foundation — the Institute for Visual History and Education, which in addition to thousands of interviews with Holocaust survivors, also contains images of interviewees’ photographs — often cherished wedding photographs that had journeyed through the Holocaust with them.

“To my surprise, we actually had four photographs of Nazi deportations in the archive which I discovered after just a five-minute search,” he says. “None of the project researchers in Germany knew the photos existed.”

Gruner said his contribution to the project includes digging deeper into the USC Shoah Foundation archives to find more photographs and raising awareness of the project in the English-speaking world — especially the United States, but also Canada, Australia and South Africa — to encourage descendants of survivors and museums to share any photographs they may have or know of.

Almost 500 Romani families are marched through the streets of Asperg, a small town in south-west Germany on May 22, 1940 as they are deported. (Photo: “Research Office for Racial Hygiene,” photographer unknown.)

Why now? And why so few photos?

The initiative is particularly timely. This July marks the 80th anniversary of the first deportation of German Jews from Nazi Germany to Auschwitz. It is also the 80th anniversary of the largest mass roundup and detention of Jewish families in France by French police collaborating with their Nazi occupiers. For two days in July 1942, more than 13,000 Jews were arrested in France and deported to camps in Nazi occupied Eastern Europe.

The evident historic and commemorative value of the multi-institutional #LastSeen Project begs the question: Why has this never been attempted before?

Gruner says that while there has been tremendous interest in documenting the Holocaust, it is only in the last 20 years that historians began thinking of photographs as important primary sources rather than merely as illustrations.

Also, Gruner says, we now live in an era with few remaining survivors, so we need to think about different ways to tell the story of the Holocaust. And one way to do that is by using images.

This brings us to another question: Why are there so few surviving photographs of the deportations? Is it because very few were taken or because they are now lying, forgotten in archives, attics or family photo albums? Or is it a result of Nazi efforts to prohibit or confiscate and destroy any images of the persecution of the Jews?

The answer, Gruner says, is “all of the above.”

While the Nazis did not officially use photography to document the deportations, most of the surviving photographs were taken by individual perpetrators, such as members of the Nazi Party’s SS or Gestapo. Some were also taken by local officials. Police commanders or mayors ordered the pictures taken as a point of pride to document how well the local authorities had succeeded in clearing their town of Jews.

Gruner says they want to identify the people in these photographs to commemorate the victims, but also to create knowledge about the perpetrators.

“Every piece of knowledge is important to understand why mass violence emerges and is perpetrated in past societies, but this helps us also understand how it can emerge in current or future societies. So, creating this kind of knowledge to understand these processes better helps us also to find possible remedies to prevent such atrocities in the future.”

If you are interested in learning more about the #LastSeen Project and how you can get involved, CAGR is hosting an online event on Aug. 29 at noon. Find more information and RSVP on the event webpage.