Marjorie Perloff: leading scholar of avant-garde and modernist poetry

Marjorie Perloff, Florence Scott Professor of English Emerita at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences championed modernist, avant-garde and experimental poetry.

Her book, Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters (The University of Chicago Press, 1977), published a year after her arrival at USC, helped bring the New York poet O’Hara his first serious critical attention.

More books would follow, and using largely jargon-free language, Perloff aimed to convey her subject matter to both scholars and the public. She believed that poetry’s value lay not necessarily in the moral message of a poem or in parsing a poet’s intent, but in the enjoyment and analysis of the language that made up the poem itself.

She would go on to author or contribute to a wide range of books throughout her long career, and she became a sought-after critic who wrote hundreds of reviews for literary magazines and journals.

Perloff died March 24. She was 92.

After fleeing Nazis, Perloff thrives in America

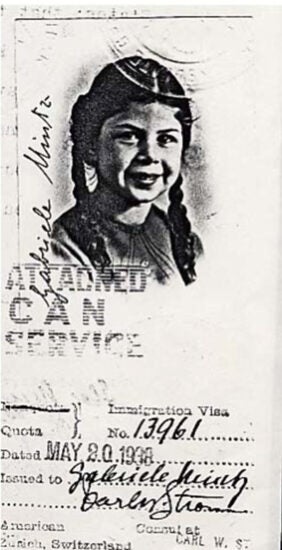

Perloff was born Gabrielle Schuller Mintz in 1931 in Vienna, Austria, into a family of secular Jewish intellectuals. Days after the Nazi-annexation of Austria in 1938, the family fled the country with just four suitcases.

They eventually settled in New York City’s Bronx borough, where Perloff took to her adopted country with enthusiasm. As a teen, she changed her name to “Marjorie” because she felt it seemed more American. She recounted her family’s escape from Vienna in her book The Vienna Paradox: A Memoir (New Directions, 2004).

She completed her undergraduate degree at Barnard College in 1953. That same year, she married Joseph Perloff, a cardiologist who helped pioneer the study of congenital heart disease in adults. They were together until his death in 2014. They had two children, Nancy and Carey, who survive her.

In 1965, she received her PhD from the Catholic University of America (CUA). She began teaching, first at CUA then at University of College Park, Maryland (UMCP) before accepting an invitation to join the English department at USC Dornsife in 1976.

Unfazed by other critics’ concerns

Perloff’s books often examined art and poetry from a macro-view, offering fresh perspectives on cultural movements. In The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage (Northwestern University Press, 1984), she made the case for a distinct line of artistic influence in modernist poetry, one she dubbed “anti-symbolist,” stretching from French poet Arthur Rimbaud to the composer John Cage. In The Futurist Moment (The University of Chicago Press, 2004), Perloff presented one of the first sweeping explorations of futurist aesthetics.

She was intrigued by the way changing modes of communication and media platforms influenced poetry, and vice versa. Her book Radical Artifice: Writing Poetry in the Age of Media (The University of Chicago Press, 1992) investigated this symbiotic relationship. She was an enthusiast of poets like Kenneth Goldsmith, whose poetry is largely a collage of other printed material like traffic reports, dubbing them “unoriginal geniuses” in her book Unoriginal Genius: Poetry by Other Means in the New Century (The University of Chicago Press, 2010).

The fact that many other critics disliked this literary style didn’t faze Perloff. She was accustomed to holding opinions that didn’t always conform with her peers. For instance, she remained an advocate of “close reading,” in which a reader parses a text’s meaning line by line, even when other scholars began to criticize this technique for not prioritizing a work’s social and political context.

John Rowe, USC Associates Chair in Humanities and professor of English, American studies and ethnicity and comparative literature, met Perloff at his first teaching position at UMCP, where Perloff was then a tenured professor. “As a more senior professor, she was very kind to me, mentoring me when there were no mentors in higher education,” says Rowe.

Although they were both specialists in avant-garde modernism, their viewpoints on theory diverged considerably over the years. Perloff was suspicious of critical theory, an approach to cultural analysis that focuses on underlying power structures. Rowe, on the other hand, helped to found The Critical Theory Institute while at the University of California, Irvine.

Academic disagreements didn’t get in the way of their enduring friendship, however. “Even as we parted ways as scholars, we shared the sort of collegiality that one finds only in the academy: a respect for proponents of other approaches who do their work rigorously and passionately. She exemplified that scholarly spirit,” says Rowe.

Perloff maintained her “verve” always

In 1986, Perloff joined Stanford University, where she served as the Sadie Dernham Patek Professor of Humanities until 2000. After her retirement, she returned to USC Dornsife to teach graduate students.

She loved her USC students and often held dinners at her home for the graduate students who attended her seminars on Beckett or contemporary poetics, say her daughters, Carey and Nancy Perloff. Even their cardiologist father participated in the “always lively and rigorous” debates, they say.

Perloff cultivated a devoted following at USC, says Susan McCabe, professor of English. “Marjorie was indefatigable — precise and rigorous yet willing to change her mind. She loved the art of conversation, enjoying the swerves of give and take. I feel honored to have known Marjorie: she was a loyal, generous friend.”

Parties at Perloff’s home in Los Angeles’ Pacific Palisades over the years were “legendary,” filled with people from all walks of life, says McCabe. Her web of friends was international, hailing from locales like France, Israel, Brazil, Sweden and China, where Perloff’s work was widely translated and read.

Perloff continued writing into her 90s. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she finished an acclaimed English translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s private notebooks, which the Austrian philosopher had written in code during World War I. Her most recent work was an introduction to a new edition of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, published earlier this year.

“When I met her in the final years of her life, Marjorie had not lost any of her verve or acumen. Her mind was luminous, discoursing on everything from Duchamp and Eliot to Sacher Torte, the latter a favorite Viennese dessert,” says Steven Minas, lecturer in English. “In our last correspondence a few days before she passed, she quoted Wittgenstein’s final words, saying that ‘I’ve had a wonderful life.’ I will always remember her indefatigable brilliance and her quick wit. You will be missed, Marjorie.”

A private memorial for Marjorie Perloff will be held June 9 at Town and Gown on USC’s University Park Campus. For further information, please contact Carey Perloff at careyperloff@gmail.com.