L.A.’s urban trees absorb more carbon than expected, USC Dornsife study finds

Key points:

Researchers found that vegetation in a section of central L.A. offsets a surprising 60% of fossil fuel emissions (CO2), particularly during the growing season.

The first-of-its-kind study used a dense array of air-quality sensors to track carbon emissions and absorption in real time, providing a more detailed picture than traditional methods.

The findings suggest that expanding urban greenery could play a bigger role in reducing the city’s carbon footprint than previously thought.

The USC-led approach could serve as a model for other cities aiming to monitor and cut emissions.

Los Angeles’ trees are working harder than we thought.

Los Angeles’ trees are working harder than we thought.

A new study from Public Exchange and USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences finds that some trees in central L.A. absorb significantly more carbon dioxide than expected — offsetting a surprising share of fossil fuel emissions during the warmer months when trees are most active.

The research, recently published in Environmental Science & Technology, provides one of the most detailed measurements to date of how urban trees impact air quality. Researchers found that vegetation in the study area absorbed up to 60% of daytime fossil fuel CO₂ emissions in spring and summer and about 30% annually — placing Los Angeles among cities with the highest recorded CO2 uptake rates.

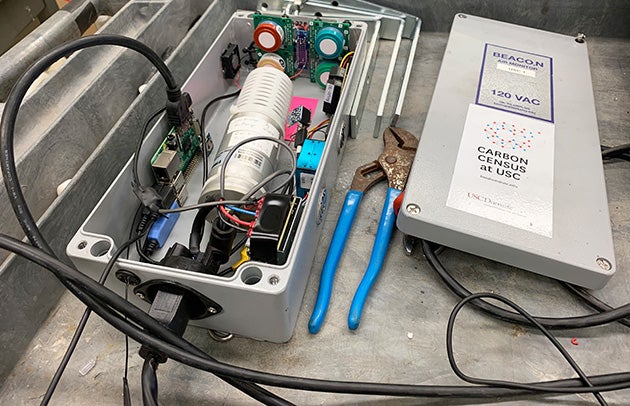

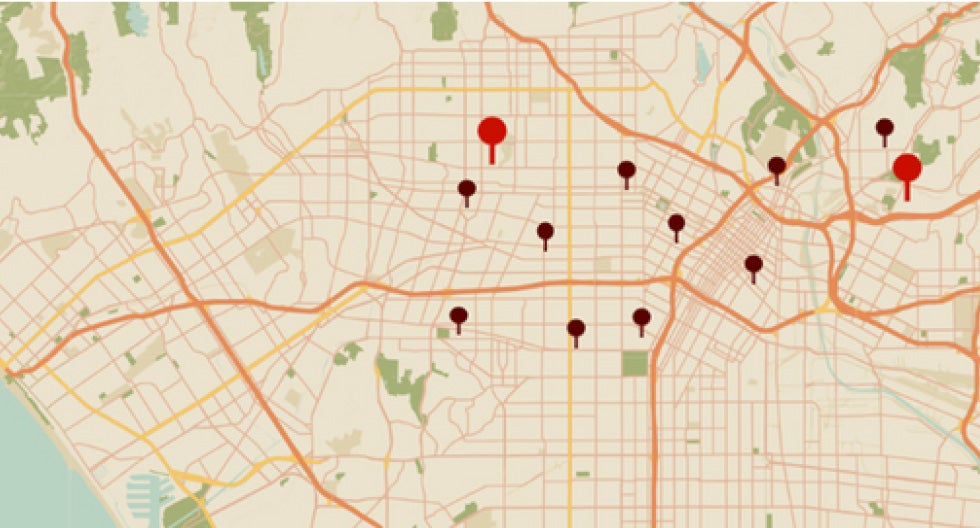

To track CO₂ in real time, the research team launched what they call the Carbon Census array, deploying 12 high-resolution BEACO₂N sensors across a 15-by-6-mile section of L.A.’s Mid-City. The sensors mapped how CO2 concentrations changed as air moved through the urban landscape, enabling researchers to factor in wind speed and direction and urban density to determine to what extent local greenery was offsetting emissions.

“You can think of emissions like passengers on a train,” said Will Berelson, who led the research and is professor of Earth sciences, environmental studies and spatial sciences at USC Dornsife. “As the wind moves pollution through the city, some gets picked up and some gets dropped off. These sensors let us see that process in real time.”

Unlike some models that estimate CO₂ levels based on fuel sales and traffic data and other models that assess the CO2 that lands on a particular sensor, this study, which ran from July 2021 to December 2022, measured CO2 directly, yielding a more precise and localized estimation of emissions.

To distinguish CO₂ emitted from fossil fuels versus natural sources, researchers tracked carbon monoxide, which behaves similarly in the atmosphere and is released when fossil fuels burn but not by plants or animals.

Although the study focused on a section of L.A., the findings provide valuable insights that could apply to other urban areas.

L.A. trees are helping — but they’re not enough

One of the study’s biggest surprises was that trees absorb the most CO₂ during summer, despite it being L.A.’s driest season. Satellite imagery shows L.A.’s urban greenery is remarkably verdant in summer, likely due to irrigation, groundwater access from leaky pipes and resilient tree species.

Still, trees can’t keep pace with emissions. As expected, CO₂ levels spiked during rush hour, reinforcing the fact that, while greenery helps, it can’t offset pollution from cars, buildings and industry on its own.

The study’s findings help inform the USC Urban Trees Initiative, a partnership between USC, the City of Los Angeles and community-based organizations focused on expanding urban greenery in communities that need it most. By identifying where trees absorb the most carbon, the research provides data-driven insights that could help guide future planting efforts.

“Nature is helping us,” Berelson said, “but we can’t rely on it to do all the work.” In fact, the study estimates that urban vegetation absorbs only about 30% of annual fossil fuel emissions in the study area, underscoring the urgent need for clean energy, improved public transit and broader emissions reductions.

Looking ahead to more carbon emissions tracking

Building on the study’s success, the USC team has expanded its sensor network, adding eight more of the BEACO₂N sensors to the east of the original study area and west into Santa Monica. These sensors, developed as part of the University of California, Berkeley’s BEACO₂N project, provide high-resolution emissions data rarely available in urban areas.

“Our goal is to monitor more areas of L.A. to define baseline values of CO2 emission and identify where vegetation is making the biggest impact and where more greenery is needed,” explained Berelson, who holds the Paxson H. Offield Professor in Coastal and Marine Systems.

He believes this real-time monitoring approach could serve as a blueprint for cities worldwide to track and reduce emissions more effectively.

Los Angeles has set a goal to become carbon-neutral by 2050, and while its urban greenery provides a natural boost, Berelson stresses that cutting fossil fuel use remains the most critical step in fighting climate change.