Life on the Rez

In the 1950s in the small village of Ball Club, Minn., a school lunch program created a nasty rift.

The area was mostly populated by Indians, recounted David Treuer. Students who resided on tribal land were entitled to a free lunch at school. Those who did not received nothing.

“It was creating a weird kind of class conflict in a community where every member was poorer than dirt,” writes Treuer in his new book Rez Life: An Indian’s Journey Through Reservation Life (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2012). “This division was tearing the community apart.”

Treuer’s father, Robert, who at the time worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), decided he would use a tactic from his union days to get all students the same benefit, which had been put in place to combat malnutrition. He got the parties involved — the BIA, the county, reservation leadership, the state board of education, the all-Indian parents’ organization — in one room with a tape recorder. Someone would be obliged to take responsibility with everything on the record, he figured.

The approach worked: all students received free lunches. Even more important, perhaps, was that the community members, who had been disenfranchised for so long by the bureaucracy surrounding them, realized they could effect change.

“‘Hey, we’ve got the power. We did this,’” was their response, recalled Treuer’s father.

Treuer fuses historical facts, reportage and memoir in Rez Life to give a detailed history of reservations in the United States, from their conception up through the modern day. While much of the history of Native Americans on the North American continent is often appalling and unjust, Treuer not only reports the injustice but the ways in which Indians resolved to turn those offenses around, as in the school lunch situation in Ball Club.

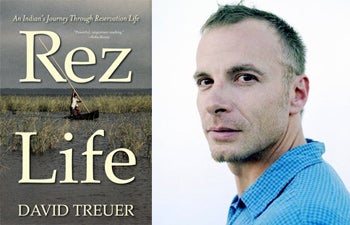

David Treuer, professor of English in USC Dornsife, is an Ojibwe Indian who grew up on Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota. In his novel Rez Life: An Indian’s Journey Through Reservation Life, he shows how Native Americans living on reservations are actively, creatively and intelligently engaged with modern life. Portrait photo by Jean-Luc Bertini.

For Treuer, the book is an opportunity to inform while offering an insider’s perspective on what it means to be Native American. Treuer, professor of English in USC Dornsife, is an Ojibwe Indian who grew up on Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota.

Oftentimes, he said, Indian life is portrayed through rhetoric of tragedy, a focus that does not offer an accurate picture of what life is like for Native Americans.

“Going into this book, I felt that our lives were usually described as poor and deficient. But what I think we’re dealing with isn’t deficit as much as surplus,” Treuer explained.

“There may be more hardship or pain, but there’s more humor,” he said. “There’s more inequality, but maybe more opportunity. I want people to take away a way of thinking about us that does not resort to the same old tragic scripts.”

Treuer’s text covers a wide swath of Native American history and reservation life from the thorny interactions with the U.S. government as the nation developed to the rise of Indian casinos and efforts at indigenous language revitalization.

When it comes to gritty details he does not pull any punches, either.

In 1778, the Treaty of Fort Pitt recognized the Delaware tribe as a sovereign nation, a first for any Native American tribe at the time. However, the compact was not made in good faith and the Delaware were betrayed almost immediately. One of the chiefs who had signed the document was murdered by his allies within a month, Treuer relayed.

“So much for the first formal, written treaty between the United States and an Indian tribe,” he writes.

Treuer reports that many years of government practices meant to extinguish tribal identities have been successful — Indian children were sent to boarding schools or adopted by non-native families to strip them of their cultures. Now a number of indigenous language schools have cropped up within reservations to teach children Indian languages and reconnect them with their heritage, a pursuit Treuer is taking part in.

Treuer, his brother and other language activists are recording and cataloging the Ojibwe language. They have been traveling to towns throughout Minnesota to record, transcribe and translate the speech of Ojibwe speakers. Their goal is to create the first Ojibwe language grammar guide.

“The U.S. government has spent millions of dollars trying to take our language away from us,” says Treuer’s brother Anton, professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University, in Rez Life. “Why would we expect the government to give it back? It’s up to us to give it back to ourselves.”

Above all, Treuer maintains that reservations are not remote, but connected to the contemporary world, a theme readers will find between the personal narratives and historical accounts in Rez Life.

“Reservations are not some tattered remnant of what was before, but places that are actively, creatively and intelligently engaged with modern life,” he said.

Rez Life is Treuer’s fifth book. He is the author of three novels — Little (Picador, 2000), The Hiawatha (Picador, 2000) and The Translation of Dr Apelles (Graywolf, 2006) — and a book of literary criticism, Native American Fiction: A User’s Manual (Graywolf, 2006).

Treuer is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, the 1996 Minnesota Book Award and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Bush Foundation and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

This summer, Treuer will be teaching a Maymester course through USC Dornsife called “Writing on the Rez.” Students will spend a month at Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota collaborating with Native American students from Bemidji State University. The course is in part a writing immersion experience and a study of Native American life with native people. Students will also create a documentary on contemporary Native American life to be screened on Leech Lake Reservation and at USC.

The course is designed to collapse the distance between what people imagine Native American life is like and how life is actually expressed on the ground. USC students will interact directly with their Native peers, and vice versa, to collectively and productively question the assumptions people share about culture and communication, and with the final documentary project, to share their discoveries with a wider audience.