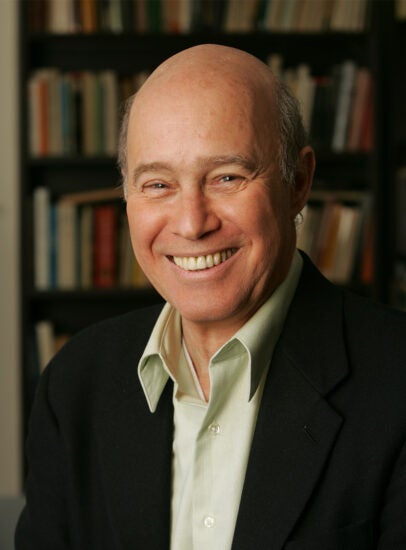

English professor whose influential courses elevated film studies in the US retires after four decades at USC

Most scholars of 18th-century English literature do not spend large stretches of time probing the cultural significance of the Hollywood sign. Or dissecting the meaning and history of celebrity, or of terrorism. Or delving into our obsession with zombies and vampires.

But then, most specialists in 18th-century literature are not Leo Braudy.

Widely recognized as one of America’s leading cultural historians and film critics, Braudy helped elevate cinema and popular culture into topics worthy of serious study.

This month, the University Professor Emeritus and Professor Emeritus of English and Art History retired after 41 years at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

From his book analyzing the films of legendary director and screenwriter Jean Renoir — which was a finalist for the National Book Award — to his work on the history of fame, to his courses on film and popular culture, beloved by generations of undergraduates, Braudy helped open the curtain to film at a moment when university departments, by and large, were slow to recognize movies as legitimate works of art.

Teenage Leo Braudy falls in love with film

Born in Philadelphia in 1941, Braudy was struck with polio at the age of four. Long stretches of forced bedrest transformed him into a voracious reader. “One thing that came out of my illness was that I learned to read very early,” says Braudy. “And that sent me down a literary path, towards academia — although my father always wanted me to be a businessman.”

Braudy whiled away his teenage years in soda shops and movie theatres. He and his friends strove to embody the evanescent quality of “coolness” that was the aspiration of most style-conscious teens in the 1950s. It was a time that Braudy documented and — wearing his cultural historian hat — analyzed in his 2013 memoir, Trying to Be Cool (Asahina & Wallace, 2013).

But as teenage Braudy was perfecting his image, he was also absorbing as many moving pictures as he could watch.

Films captured Braudy and shaped his understanding of stories. Later, as a young scholar, he would be fascinated by the relationship between historical narratives and fiction. But it was the cinema that first sparked his curiosity about what historical narratives share with invented stories.

“My view of fiction and nonfiction was nurtured by the movies,” he says.

As a young scholar, Braudy dives into “incoherent” literature

As an undergraduate at Swarthmore, Braudy fell for 17th- and 18th-century literature. Those two centuries “were very generative,” he says. “There were so many new things going on. I was attracted by its incoherence, and I wanted to find the through line.”

After his college graduation, Braudy went to Yale, where he completed an MA and PhD on the relationship between history and novel writing in the 18th century. His first academic publications set the tone for the rest of his career: a paper on Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary and an essay on Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Between the late 1960s and early ’80s, Braudy was playing “musical chairs,” as he puts it, up and down the East Coast, with tenure-track posts in the English departments at Yale, Columbia and Johns Hopkins. “It was an energetic time. Departments were trying to build themselves up in different subject areas by courting people,” he notes.

During that period, Braudy published his book on Jean Renoir, the first English-language study on the director, as well as The World in a Frame (Doubleday, 1976), his now-classic volume of film theory, still in print almost 50 years later. Meanwhile, he spent summers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he helped build a film studies program and developed a groundbreaking course on film and popular culture. The syllabus for that course became a model for similar ones around the country.

“It was a time of great ferment,” he says. “There was this effort to create film studies as its own field.” But Braudy didn’t just study film. He was in them, too, with roles in the John Waters satire Polyester and in Robert Kramer’s 1970 drama Ice.

USC and Southern California beckon Braudy

In 1983, Braudy accepted an offer from USC, and he and his wife, the painter Dorothy Braudy, moved to Los Angeles, where they bought a Spanish-style house on the edge of Griffith Park, where they still live. He was immediately struck by USC’s close-knit community, which compared favorably with the East Coast.

“When I arrived here, there was all this talk of the Trojan family, which I initially thought was just a branding thing,” he says. “But I quickly realized it was true. There’s a cohesiveness here, a way in which people look out for each other and take joy in relating to each other, both academically and personally.”

USC’s encouragement of interdisciplinary scholarship also attracted him, and Southern California was the perfect location for writing about movies. Plus, his wife hailed originally from L.A. “She always considered it appropriate for it to be warm at Christmas,” he says.

Across his four decades at USC Dornsife, Braudy taught courses and wrote a celebrated cultural history of fame and a book on the meaning of the Hollywood sign. His 2003 book, From Chivalry to Terrorism: War and the Changing Nature of Masculinity (Alfred A. Knopf, 2003),” a study of the changing nature of masculinity, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and listed as Best of the Best by the Los Angeles Times.

The Braudys support fellow Trojans

He remains dedicated to the USC Dornsife community, a commitment demonstrated by his many years of service, including four years as a member of the University Committee on Academic Review and five years as the chair of the University Committee on Appointments, Promotions and Tenure.

Braudy and his wife have also been generous donors.

In 2016, the couple wished to make a gift that would be as impactful as possible. Upon learning about food insecurity on campus, they started what became the Trojan Food Pantry, which offers fresh food and other urgently required supplies for students in need. “We are proud to have planted the first seeds to help students in this way,” says Braudy.

Braudy’s retirement will free up time to spend with his two sons and three grandsons, and his close-knit neighborhood community of friends. But scholarship will always be central to his life.

“A friend of mine once said that, in academia, retirement is redundant. By which he meant you end up doing very similar things you did before you retired — reading books and writing articles,” he says. “So, I’m not quite stepping into the dark. I have projects that I’ve had on the back burner for years that I’m looking forward to getting back to.”