In 1949, Kathy Fiscus fell down a well. What happened next is breaking news

On the afternoon of April 8, 1949, three-year-old Kathy Fiscus ran across an expansive field of spring grass with her sister, Barbara, and cousin, Gus. She and her family lived in the Los Angeles suburb of San Marino, at the base of the San Gabriel foothills.

High above them winked the newly installed KTLA transmission tower on the tip of Mt. Wilson. It was now broadcasting sports and shows into televisions across the Los Angeles basin, although TV was still so new many people didn’t quite know what to think of it.

Kathy’s mother, Alice, worked in the kitchen, glancing out of the window occasionally as the children played. Suddenly, she noticed Kathy was no longer among the group.

Alice went outside to look and eventually stumbled across a 14-inch-wide hole in the weeds. Kathy’s cries radiated up from the dark mouth. Somehow, the toddler had tumbled nine stories into an uncovered well.

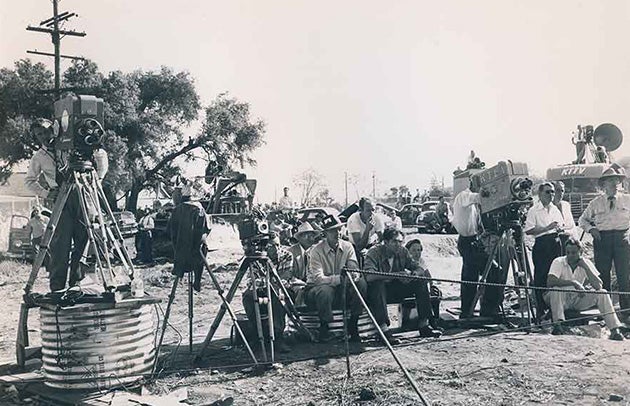

Within hours, the little plot of land would erupt into a frenzy of activity as rescue workers and neighbors worked to retrieve Kathy. Cranes, bulldozers, drills and trucks arrived. Groups of gawkers gathered to observe and pray.

Drawn to the excitement, TV and radio reporters showed up. For the final 24 hours of the two-day rescue operation, the scene was broadcast to TVs across Los Angeles and on radio waves around the nation, thanks to the towers on the mountain above. The phenomenon of live, breaking TV news coverage was born.

A historian’s obsession

Bill Deverell, professor of history, spatial sciences and environmental studies at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and author of the new book Kathy Fiscus: A Tragedy That Transfixed the Nation, professes to a near obsession with this event. Deverell lives in nearby Pasadena and has visited the site of Kathy’s well dozens of times.

The well has been bulldozed and is unmarked, but GIS tracking by researchers at USC Dornsife’s Spatial Sciences Institute helped Deverell pinpoint the exact location. Buried under San Marino High School’s football field lies the infamous site.

Aside from proximity, Deverell’s interest grew partly because of his own daughter, who was a toddler like Kathy when he first began his research. Honoring the trauma and poignancy of Kathy’s own story, while also tackling the larger impact of the event on the nation was a challenge that took him over a decade to complete.

“I knew there was a lot of misinformation out there about it, so I wanted to get the story right. It’s a very dramatic, very unusual event,” says Deverell. “It’s the hardest book I’ve ever written and it’s also the shortest book I’ve ever written.”

Rescuers — and spectacle — arrive

For 48 hours, the area around Kathy’s well felt like the center of the world. Firemen and police arrived first, who then called in heavy equipment and workmen to attempt to dig their way to Kathy. No one was quite sure how to rescue her. At one point they lowered a rope, carefully instructing her to slip the knot around her waist, but the effort failed, and she likely fell even lower down the shaft.

Despite the tragic circumstances, the scene near Kathy’s well soon resembled something akin to a movie set. Jockeys from the nearby race track, a sideshow thin man and skinny children volunteered to go in after her. Johnny Roventini, the spokesman for Phillip Morris cigarettes and who stood less than 4 feet tall, arrived at the scene decked out in his signature bellhop uniform to offer his services.

“Someone thought that maybe they should go get the munchkin actors from The Wizard of Oz,” says Deverell. “It just gets weird, and I think that’s part of the newsworthiness.”

Thousands of onlookers streamed in, pressing against the fence for a glimpse of the action and calling out suggestions. Snack vendors roamed the grounds peddling food. Illuminating the scene were bright klieg lights that the 20th Century Fox studio had sent over.

Lights, camera, action

Furthering the impression of a film set, two KTLA TV reporters and their crew pushed through the crowds, broadcasting everything to viewers at home. Earlier that day, Klaus Landsberg, KTLA’s station manager, had made the innovative decision to bring a news crew to the scene itself — something it had never tried before. Another news station, KTTV followed suit.

Nearly 30 hours of the ordeal were thus broadcast live on television. They interviewed bystanders and workmen and filmed the digging. “A lot of it is just focused on the hole, in hopes that she’s going to pop out in the arms of a rescuer,” says Deverell.

Televisions were still relatively rare in the area. Only 20,000 or so residents had them at home and viewers had been a little unsure what this new medium could offer that radio didn’t.

The Fiscus tragedy revealed TV’s draw. For two days, Los Angeles residents were glued to their sets. Hundreds gathered in front of department store windows filled with TV displays, while others raced over to their neighbors’ houses to tune in.

The cameras were still on when Paul Hanson, the physician that had delivered Kathy at birth, announced over a crackling P.A. that Kathy had not survived the fall. Rescuers and bystanders began to cry. Viewers at home wept alongside them, miles away but still present thanks to KTLA’s coverage.

The Nation’s Child

The Kathy Fiscus tragedy cemented television as a vital source of information and entertainment, says Deverell.

“After this event, the number of TV sets sold in greater L.A. goes through the roof,” says Deverell. “I think there’s probably about 20,000 TVs in 1949 in greater Los Angeles County and within a handful years I think it’s 300,000.”

Live news coverage became the new norm in America, with millions tuning in just 20 years later to watch a man take the first steps on the moon in 1969.

The event also changed laws. In a horrible twist of irony, Kathy’s father was a water company superintendent who had been in Sacramento, testifying for the need to cap abandoned wells due to pollution concerns, the very day she fell in. Laws ordering the sealing of wells quickly passed in numerous states, many named the “Kathy Fiscus Law.”

The event became lodged in the nation’s collective memory. Timmy never actually falls in a well during the classic television show Lassie; the iconic line “Timmy fell down a well!” arose from the country’s recollection of Kathy’s fall instead.

It had a very personal effect on women, says Deverell. “I knew about the creation of live television news out of this story. What I didn’t know was that it would change naming patterns for little girls during that baby boom. The number of babies named Kathy skyrocketed in the 1950s.

“Thousands of women, either pregnant or those who were going to be pregnant soon, wrote to Kathy’s mom and said: ‘If I have a little girl, I’m going to name her Kathy.’”

KTLA’s cameras and the radio reporters dashing between the crowds had briefly made Kathy the nation’s child, her story shimmering out on transmission waves from those newly minted towers miles above the little grassy field.