Los Angeles: where the future happens first

Its urban landscape and iconic buildings have served time and again as backdrops for dystopian visions of the future. The long list of leading science fiction writers who have called the city home includes such stars of the genre as Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Robert Heinlein and Octavia Butler.

The place — of course — is Los Angeles, a city long hailed as one of the world’s great science fiction capitals.

“Science Fiction L.A.: Words and World Building in the City of Angels,” a two-day conference organized by William Deverell, professor of history and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW), and David Ulin, assistant professor of the practice of English, explored how Southern California’s particular blend of high and pop culture made L.A. an incubator of the form.

“Los Angeles can be seen as the ‘City of the Future’ because so much of the futurism of science fiction is set against the backdrop of the city, or written here,” Deverell said. “The sheer decentralization of Los Angeles sets it apart as unusual in the world lexicon of cities. Add to that its reputation for being at the cutting edge of popular culture and its iconic architectural landscape, and all those things suggest that Los Angeles is, and can be, a trendsetter.”

Sponsored by ICW, USC Dornsife and the USC Sidney Harman Academy for Polymathic Study, the conference began with a special screening of Spike Jonze’s critically acclaimed film Her at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Hollywood. The science fiction drama about a lonely writer who falls in love with an intuitive operating system was filmed against the backdrop of a futuristic version of L.A., with the Shanghai skyline standing in for a built-up City of Angels.

David Ulin, assistant professor of the practice of English, introduces a discussion about legendary science fiction author Philip K. Dick. Photo courtesy of Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

“While the movie offers a sobering critique of digital culture, it paints a remarkably rosy picture of where the city is headed, at least in terms of its architecture and design,” said Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, who gave an introductory talk prior to the screening.

L.A., he said, has always been a place of reinvention.

“It’s been a laboratory, or proving ground, for new ideas about architecture and, increasingly in recent decades, new ideas about urbanism, too. It’s a city that is trying to reinvent itself for the nth time, and that is the spirit that drives science fiction.”

L.A.: apocalyptic or bucolic?

Conference participants reconvened the following day at USC’s Doheny Library to hear panel discussions about “Artificial Intelligence, Science Fiction and the Future,” and “Los Angeles: The Capital of Science Fiction,” a discussion moderated by Ulin and featuring M.G. Lord, assistant professor of the practice of English.

“Even as we moved from the late 19th into the early 20th century, Los Angeles was seen as a place that invites a kind of apocalyptic future, so there’s a great deal of writing about L.A. falling into the ocean, or being taken over by hordes of rampaging animals or insects,” Deverell said. “That’s an old literature that Los Angeles seems to sustain, which is in many ways the flip-side of Los Angeles as a bucolic place of nature and harmony.”

As Deverell and Hawthorne noted, the physical features of the L.A. landscape lend themselves to settings for science fiction movies. The L.A. River has long featured as a site of destruction and apocalypse, while the California desert lends its eerie isolation to the depiction of alien planets. L.A. architectural monuments have also played key roles in science fiction films, among them Frank Lloyd Wright’s textile block Ennis House and the 19th-century Bradbury Building, both of which featured prominently in the movie Blade Runner’s vision of a ruined future.

The draw of L.A.

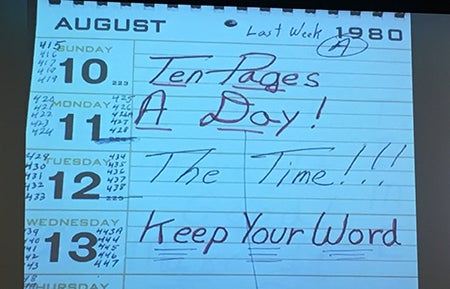

Madeleine Brand, host of KCRW’s Press Play, moderated a discussion about celebrated African-American science fiction novelist Octavia Butler, a Pasadena native whose archive is held at The Huntington Library. Despite the lack of role models and the handicaps of poverty, Butler’s determination to succeed as a sci-fi writer brought her significant acclaim, which Deverell believes is still growing today.

A page from the archive of acclaimed Los Angeles science fiction author Octavia Butler shows her determination to stick to her writing goals. Photo by Susan Bell.

Other sessions focused on sci-fi stars Bradbury and Dick and their relationship with L.A. By the time Bradbury was 17 years old, he was one of the youngest members of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, which met regularly during the Great Depression at Clifton’s Cafeteria in downtown L.A.

Ulin said Hollywood was undoubtedly a major draw for science fiction writers looking to make money from their work, particularly in the 1950s and ’60s when the mainstream publishing industry looked down its nose at genre fiction.

“Hollywood embraced science fiction storytelling in a less marginalized way than the publishing industry,” Ulin said, “so there were financial and creative opportunities for sci-fi writers in Los Angeles that didn’t exist elsewhere.”

Sophomore Julia Doherty, a double major in international relations (global business) and religion, was one of 20 students from the USC Sydney Harman Academy for Polymathic Study invited to participate in the conference.

“It was incredible to be able to hear panel discussions involving such diversely knowledgeable and involved people,” she said. “I very much enjoyed the conversation surrounding how depictions of L.A. in science fiction are beginning to shift from dystopian to utopian.”

To anyone expressing surprise at a historian’s interest in science fiction, Deverell noted that the genre frequently involves time travel. Asked which period he would visit if he had a time machine, he responded, “As an American historian, I would probably go to the period of Westward Expansion. I would try to be on the ground as the Civil War began to brew. I would be fascinated to visit Gold Rush San Francisco and late 19th-century New York City as it began its boom period of urbanization and immigration.”

“Historians are natural time travelers,” Deverell said. “We bring to the past the puzzles of our present and we bring to our present, the puzzles of our past.”