Feelings, Oh, Oh, Oh!

Even a cognoscente of the written word like Aimee Bender admits the difficulty in communicating feelings.

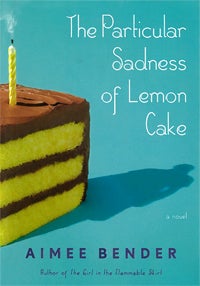

In her new novel, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake (Random House), the professor of English in USC College circumvents that mortal dilemma. On her 9th birthday, her protagonist and narrator Rose Edelstein bites into a lemon cake and is overpowered by aching hollowness. The emotions are coming from her mother who baked the cake from scratch.

It tastes empty, I said.

The cake? She laughed a little, startled. Is it that bad? Did I miss an ingredient?

No, I said. Not like that. Like you were away? You feel okay?

I kept shaking my head. The words, stupid words, which made no sense.

Rose’s strange sensor extends to every morsel of food she puts in her mouth. She tastes her father’s distraction in his butterscotch pudding. She feels a deli clerk’s desperate, “love me, love me,” in each bite of her ham-and-cheese sandwich. Her older brother Joseph’s toast with butter, jam and sugar sprinkles has such a rank taste of blankness and graininess — like a sea anemone — that she spits it into a napkin. Flooded with emotions, the young girl tries to rip her own mouth off her face:

I TASTED YOU, I said. GET OUT OF MY MOUTH.

“The food allowed me to write about feelings in a way that was super concrete,” Bender says. “So I can talk about lettuce leaves instead of having to talk about the kind of amorphous, ethereal, ephemeral world of emotions which are so — they can be hard to talk about.”

Although an avid traveler reared in West L.A., Bender lacks the world weariness seen in her characters. The author could have emerged from the Iowa cornfields. She has a generous smile and steady gaze that radiates natural warmth. No makeup, her dark, wavy hair falls around her shoulders. Lithe and wearing a delicate white, cotton blouse and black jeans, she leans forward when emphasizing a point, elbows and forearms extended on her desk.

Right now she’s making a point for her “frustrated readers.” Lemon Cake reviews have been stellar (Bender is “the master of quiet hysteria,” the Los Angeles Times said) and Oprah Winfrey placed the book on her 2010 summer reading list. But some have taken to Twitter and Amazon.com to express their confusion about what the story really means.

Rose’s extra-strength empathy is not the only extraordinary talent in the Edelstein family. Her emotionally absent father has what might be a gift but he’s too petrified to go near it. Her brilliant, troubled and possibly disturbed brother Joseph has a bizarre way of vanishing, and it’s not your typical teenage escapism. Or is it? Magical realism is at play here.

“I could never really discern between the fact and fantasy part of Joseph’s life,” cries Bookworm-Red Rock on Amazon.com. “Was he psychotic, autistic, or are we to believe that he really possessed extraordinary powers? I am so confused.”

The “talents” of each member of the dysfunctional Edelstein family become a sort of Rorschach test and Bender makes the reader do much of the work to eke out specific meaning.

“I can sense if it feels true to me; if it feels that I’m onto something,” Bender says. “If the metaphor is charged, then I’m interested in what I’m writing. But I don’t know what it means. I kind of try to shape it the best I can. So when people are frustrated about the meaning, my wondering is how do they feel? That’s the thing. I want the reader to have some sort of feeling at the end. And I think that some people do and some people don’t.”

Bender is exploring empathy and sensitivities and awareness and coping and families. “And all that mucky underground territory that influences our behavior,” she says.

“What’s the line between talent and illness?” Bender asks. “What can land on one person and be a talent and land on another person and be an illness? What makes that so hard to understand? There’s something painful about that. We all know people on both sides of that scenario.”

She recalls the gut-wrenching rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” by singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley who drowned in Memphis’ Wolf River Harbor in 1997 at age 30.

“His rendition is so raw,” Bender says. “When you listen to it, it feels like a person with every pore open to the world. It’s unbelievably beautiful. But there is no surprise that he died, there really is not. How did he walk outside? How did he have a conversation? He’s like a living pulsing nerve.”

The same can be said for each character in Lemon Cake, all varying degrees of open wounds. To truly understand how they cope, just go with your gut.