Far from Paradise

Invited into the living quarters of undocumented migrant domestic workers in the oil-rich city of Dubai, Lucero Noyola was shocked by what she saw.

“Fourteen people were sharing one room,” said the junior majoring in psychology and sociology at USC Dornsife. “They slept in bunk beds, but to save money some were sharing one bed. Many had erected flimsy plywood shelves at the end of the bed and those held all their belongings. In another apartment, we saw plywood being used to divide one room into five makeshift cubicles.”

Like Noyola, Cathleen McCaffery, a senior majoring in English with a creative writing emphasis, was impressed with the female undocumented migrant workers she met.

“The women I met have a sense of solidarity due to their illegal status,” McCaffery said. “Hearing their stories was a powerful experience. There was such a sense of community and togetherness. It was both heartbreaking and inspiring.”

Noyola and McCaffery spent three weeks in the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) with 8 classmates as part of the Problems Without Passports (PWP) course “Forced Labor and Human Trafficking in Dubai” led by Rhacel Parreñas, professor of gender studies and sociology and chair of sociology at USC Dornsife.

The 10 USC Dornsife students who participated in the Problems Without Passports (PWP) trip to Dubai are (from left) Stevie Gibbs, Jennifer Glaeser, Cathleen McCafferty, Alakea Woods, Hannah James, Vanessa Nahigian, Lucero Noyola, Irene Hu, Tamara Cesaretti and Min Cho. Photos courtesy of Min Cho.

A global hub — more than 50 million people pass through its airport each year — Dubai is a booming finance center where the lives of the fabulously wealthy, and the very poor who service their needs, collide. Migrants make up 95 percent of the labor force. They lack minimum wage protection and are legally bound to work only for their sponsoring employer.

Vulnerable groups include Bangladeshi construction workers, Ethiopian, Filipino and Indonesian domestic workers, low-wage janitors and various other “company” workers employed under conditions of legal servitude. Many agree to these conditions in order to send money back home to their families.

As legal servitude is the norm for low-wage migrant workers in Dubai, many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) including Human Rights Watch perceive the country as a hotbed of forced labor and human trafficking.

Conducting independent field research on labor migrants vulnerable to forced labor and human trafficking, students learned the complexities and nuances of their situation.

They met various constituents involved in labor migration, including government and diplomatic officials, labor recruiters, NGOs, migrant workers and runaways.

The class aimed to discover why individuals knowingly agree to legal servitude, the ways human rights discourses shape — or fail to shape — the conditions of employment and standards of employment across various occupations in Dubai. They also studied the ways gender, race and ethnicity shape labor migration.

“I believe the students gained a more nuanced perspective on human trafficking,” Parreñas said. “I want them to see that the problem exists, but that it’s not black and white and that there are multiple solutions. Exploitation happens not because of individual bad behavior, but as a more systemic problem.”

PWP participant Alakea Woods wears an abaya to visit the Sheik Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates.

In Dubai, students had access to some of the most vulnerable migrant workers in the world — workers that many academics have portrayed as inaccessible, Parreñas said. The data and reports compiled by the students will be submitted to Human Rights Watch at the end of the course.

Noyola, who chose to focus on the experiences of Filipino migrant domestic workers, noted the ambiguity of their contracts.

“While their contracts state they will be ‘treated in a just and humane manner and work solely for employer and his immediate family,’ many domestic workers I interviewed said two to three families actually lived in their employer’s home.

“It is common for Arabic families to have such housing arrangements because of their family-oriented culture, but this leaves the migrant domestic worker at the service of many more people than the sole employers, resulting in an overload of work duties.”

McCaffery, who studied Arabic for three semesters at USC Dornsife and plans to pursue a graduate degree that focuses on the region, had also volunteered with Amnesty International in high school, working on its human sex trafficking campaign.

She focused on labor recruiting agencies and their legal and ethical role in forced labor and labor migration into the U.A.E. She interviewed labor recruiters and government officials at various consulates and talked to domestic workers and other migrant workers about their experiences with such agencies. McCaffery said the trip had been an eye-opening experience.

“I realized that the situation of human trafficking and forced labor in Dubai, but also in the Khaleej region as a whole, is complex and depends on a multitude of factors,” she said. “There is no simple solution.

“In most cases, at least in my experience, human trafficking does not seem like the right term to use. Forced labor seems to be more accurate.”

“Rescuing” migrant workers is the usual solution presented to trafficking but, Parreñas said, the students found that often a slight improvement in working conditions would be a more effective solution.

Undergraduate Lucero Noyola describes the Sheik Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi as “breathtakingly beautiful.” The mosque is the eighth largest in the world.

Hannah James, a sophomore majoring in international relations (global business), compared potential opportunities to the risks a female domestic worker faces coming to Dubai.

She was struck by the workers’ dedication to improving the lives of their families back home.

“I spoke with one woman who suffered through almost seven years in three different abusive households,” James said. “When I asked her why she continued to choose to work as a domestic worker and apply for new contracts, she replied that it was a sacrifice she had to make for her family. She wanted to do it for their sake. Every woman I interviewed cited their family as their reason for being there and their reason for staying.”

Students found workers’ living conditions varied widely. Some had their own room and bathroom, their employer paid for their personal items and food, gave them a day off, and allowed them to use technology. However, many were not so fortunate.

“Some women spoke of having to sleep in a room with young children and being on call 24/7,” James said. “One woman was forced to sleep outside. Many cited a lack of food and water, little time to sleep, being unable to leave the house and being unable to use technology, which meant they weren’t able to talk to their families for months at a time.”

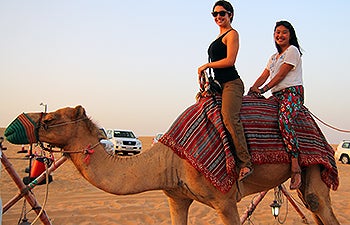

Undergraduates Stevie Gibbs (left) and Irene Hu try out camel riding during a desert safari.

For the students, the trip was mostly, but not all, work. During their leisure time, they rode camels on a desert safari and got a private tour of the Sheik Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi, which Noyola described as “breathtakingly beautiful.”

“In order to truly experience Dubai, you have to dig a little deeper,” James said. “Of course I enjoyed doing the touristy things, but the most fascinating nights were those spent in Al Satwa, where thousands of migrant workers live.”