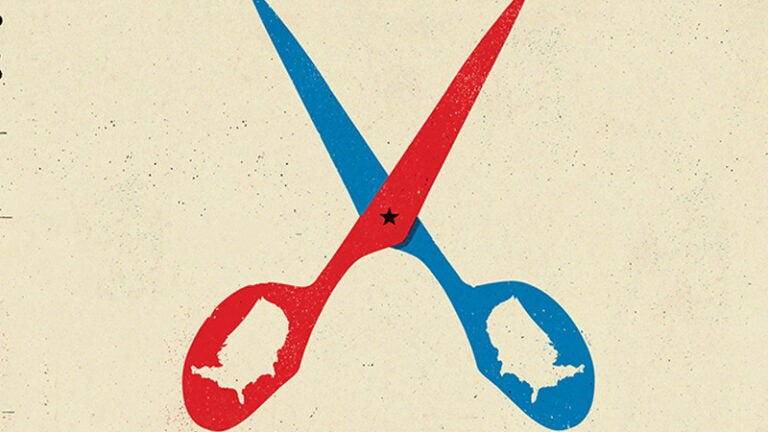

Divided We Fall

Political forecaster Nate Silver said it best: “‘With the exception of the 2016 election’ will be a common phrase in Ph.D. dissertations in 2044.”

This presidential election is the first or second that my generation will have voted in. When the dust clears, we have a simple job: to ensure that the extreme political divisiveness that has defined the period leading up to this election remains the exception and does not become the norm.

The task of understanding how to accomplish that was before me and five other USC students when we traveled to Washington, D.C., last summer. Led by Robert Shrum, Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics and professor of the practice of political science, we had come to explore the workings of our nation’s capital.

I’ll never forget the first thing we learned: Starting sometime in the 1980s, the most moderate Democrats moved further left than the most moderate Republican. The American people, their constituents, soon followed suit. This may seem shocking, but according to The Washington Post, “Before the 1980s, if you knew which party an American voted for, you couldn’t predict very well whether the person held liberal or conservative views.”

That’s because of a logical observation most people are capable of understanding, but incapable of following: How you think about a particular issue in a given political party’s platform should have little or no value for predicting how you will think about another issue.

For example: The Republican Party platform is both pro-gun rights and skeptical of human-caused climate change. But is there a commonality in these issues that should enable one to predict how a Republican gun owner will think about the environment? Of course not. The two are totally distinct issues. And yet, the vast majority of climate change skeptics turn out to be strong gun-rights advocates.

The same is true for Democrats: Despite little issue overlap, most supporters of the Affordable Care Act are also strong believers in the science supporting human-caused climate change.

After listening to Professor Shrum moderate panels with icons like former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan, Chris Matthews and Chuck Todd of MSNBC, The Washington Post’s George Will, and other D.C. thought leaders, the path forward seemed much clearer. I’ll highlight two suggestions we developed.

First, revamp the Washington — and by extension, the American — political culture. For years, members of Congress lived in Washington, D.C. That’s no longer the case. They jet home for long weekends to campaign, and many no longer have permanent residences in the district. Beyond that, cross-party interactions often seem forced. Gone are the days when President Reagan and Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill would share a 5 o’clock scotch and hammer out compromises.

Corporations, by contrast, promote after-work gatherings. They know that when their people are happy together outside the office, they work better inside the office. The same is true of Congress. But Washington isn’t a vacuum — improving cross-party dialogue all across the country is both possible and necessary.

Second, fix the media echo chamber. In a blatant example of confirmation bias — surrounding oneself with like-minded opinions to feed the notion of one’s correctness — most liberals I know watch MSNBC, and most conservatives watch Fox. That practice has made us less willing to consider each other’s opinions. Challenge yourself to watch or read a news source that you don’t agree with. It might open your eyes.

I don’t mean our opinions should become more vanilla-flavor bland, but rather that we should be more receptive to flexibility. If you think some give-and-take between the parties is a bad idea, ask yourself if it’s not an improvement over what we have now.

Nathaniel Haas earned his bachelor’s degree from USC Dornsife in 2015 with a double major in political science and economics. He currently is a law student at USC Gould School of Law.

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2016-Spring 2017 issue >>