Mayor’s civic working group addresses Los Angeles memorials and monuments

Natalia Molina, a third-generation native of Los Angeles, recalls watching TV growing up.

“I would see these shows filmed in Los Angeles and think, ‘That’s not my L.A.,” says Molina, Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and a 2020 MacArthur Fellow.

“It never really felt like my California was represented in terms of the immigrant community, people of color and working-class neighborhoods and the complexity of them,” Molina says. “And when these neighborhoods were represented, they were represented as monolithic barrios.”

Depictions of Los Angeles as it really is — and was — lie at the heart of a working group Molina participated in, along with other USC Dornsife faculty members, that examined how L.A. can more honestly examine its past and, moving forward, accurately and appropriately commemorate triumphant and tragic moments in the city’s history.

Past Due, a work of the Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group that was overseen by Christopher Hawthorne, a professor of the practice of English at USC Dornsife and the city of L.A.’s chief design officer, recently was published in a 166-page print version and online at civicmemory.la.

More than 40 leading historians, architects, artists, indigenous leaders, city officials, scholars, and cultural leaders spent 18 months coming up with 18 key recommendations for how L.A. can commemorate and memorialize formative moments that have gone unrecognized, reshape L.A.’s civic identity and view the past as a window into the future.

“This is much more than about building memorials,” says fellow USC Dornsife participant William Deverell, professor of history, spatial sciences and environmental studies and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, which produced the report. (The report was underwritten by the Getty Foundation.)

“We wanted to raise questions about how material memorials need to be,” Deverell adds. “The tried-and-true convention is that they have to be a statue or a plaque. Those may have their utility, but as we’ve seen in recent events, they can be appropriately challenged maybe because they’ve lasted a little too long and maybe things have changed.”

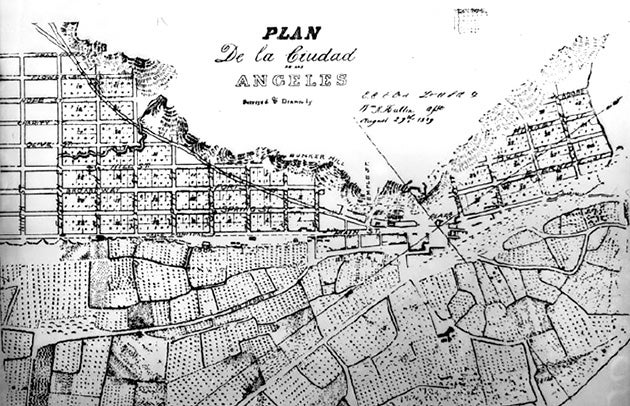

A map drawn in August 1849 depicts the city of L.A. (Photo: Courtesy of USC Libraries/California Historical Society.)

The group raised questions about less permanent ways of paying tribute to the past, including grassroots community events, and how useful they might be, Deverell says. “We wanted to air out those kinds of open-ended questions and wait to see how the communities respond.”

Far from a finished project, Molina, Deverell and Hawthorne call Past Due a starting point and a call to action.

“The last thing we wanted to do was to suggest this work is done and Los Angeles has wrestled with these issues, and let’s move on,” Deverell says.

Hawthorne says the report isn’t meant as an instruction manual.

“We’re not designing memorials, and we’re not naming structures that need to be taken down,” Hawthorne says. “This report really is meant to be a guidebook to help frame decisions and equitable processes related to these important issues.”

Although Hawthorne says the Civic Memory Working Group, which first convened in November 2019, was inspired by debates happening around the country about Confederate statues and other fraught examples of American commemoration, the aim was to ground the larger debate firmly and unmistakably in Los Angeles, “a city whose relationship with the past and the broader notion of civic memory has long been particular, even peculiar.”

Still, there are some concrete recommendations among the 18 detailed in Past Due, including building a memorial to the victims of the Anti-Chinese Massacre of 1871, an event that will mark its 150th anniversary this October, as well as developing a memorial or memorials to victims of COVID-19.

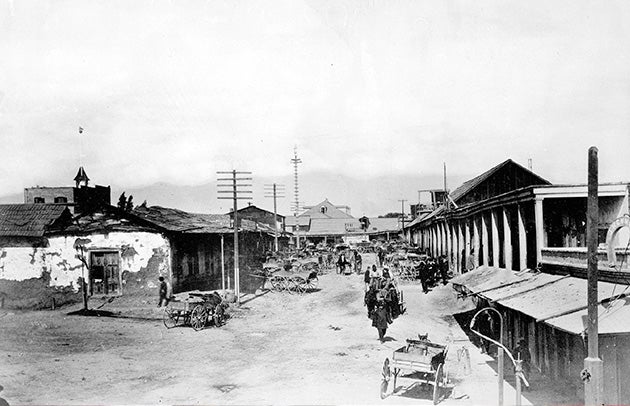

This 1882 photo looks east down Calle de los Negros toward the plaza, L.A. (Photo: Courtesy of L.A. Public Library/Security Pacific National Bank Photo Collection.)

Also participating in the working group from USC Dornsife were David Ulin, associate professor of the practice of English, and Laura Dominguez, Deverell’s doctoral student who specializes in heritage conservation.

Deverell says the working group was “one of the most magnificent committees I’ve ever worked on.”

He adds, “There is no finish line for this project. As we think about our past, that’s an endless quest to seek out community, to work at the levels of memorialization and acknowledgement — that’s endless, as it should be.”

The Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West is planning a series of programmatic events wrapped around the notions, concepts and themes of civic memory.

“Statues get put up at a certain moment that says more about the moment they get put up than about the history they supposedly are representing,” Deverell says. “One of our questions was, can we push along dialogues that encourage people to go to sites of memorialization and maybe reinterpret them?”

Molina says participating in the project has made her look at L.A. differently.

“I was on a hike in Griffith Park recently and I starting to think, ‘Who was Griffith, and how did he get all that land.’”

Dominguez says the report imagines new possibilities for repair in light of the pandemic and recent uprisings for racial justice.

“As we think about what the last year means to us, Angelenos also have an opportunity to unravel some of the long-held fantasies we’ve inherited about our city’s history,” Dominguez says. “Going forward, my hope is that our efforts to conserve and commemorate our cultural heritage will be less about tangible objects and more about the dynamic ways in which our communities make sense of the past.”