Close Look at Baldwin Hills

A state-of-the-art environmental assessment of Los Angeles’ Baldwin Hills is underway, led by Travis Longcore, associate professor (research) of spatial sciences at USC Dornsife.

The 18-month project is a cooperative effort for the Baldwin Hills Conservancy and the Baldwin Hills Regional Conservation Authority, with technical support from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles.

Much of Longcore’s research involves the interface between the natural and the built environments. That certainly applies to the Baldwin Hills — the area includes a set of parks and open spaces surrounded by houses, a cemetery and one of the most active petroleum fields in L.A. County.

“I like this project because I’m interested in ‘urban nature,’ and what can persist in an urban environment,” said Longcore, who is affiliated with the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies.

Longcore has been in this line of work since 1999, when he received his Ph.D. in geography from UCLA and joined USC as a postdoctoral scholar in the USC Center for Sustainable Cities. In 2008, he was named an associate research professor, and today his time is split between research with the USC Spatial Sciences Institute (SSI) and teaching in the USC School of Architecture. This project utilizes all of his interdisciplinary skills.

“It’s been almost 15 years since there’s been a real update of the biota in Baldwin Hills,” Longcore said. “So I was approached by the conservancy and the conservation authority to do a selective update of some resources that were not previously investigated in detail.”

For example, there were no bat surveys done 15 years ago.

“The surveys of the reptiles and amphibians weren’t extensive, and there was no vegetation map that stitched together all of the properties,” he said. “There’s a map, but the middle is missing — it’s like ancient maps of the world that have big blank spots in them — and that’s because the people who did the initial surveys didn’t have access to all of the land.”

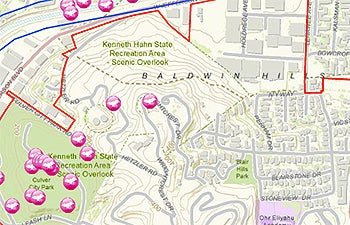

Display of bat detections using “Collector App” for GIS. Graphic courtesy of Travis Longcore.

Access to all of the land might not be possible for the current update either. But Longcore and his colleagues will get a better picture of it with data and technology not available 15 years ago, by using sophisticated software and datasets licensed to the SSI. That includes the widely used ArcGIS geographic information system, maps with high-resolution topography, and extremely high-resolution aerial photographs collected by the Los Angeles Region Imagery Acquisition Consortium Program. The datasets include images of the Baldwin Hills so detailed that they provide up to four-inch resolution.

“I knew we had this aerial imagery to bring to the project,” Longcore said. “Now we can look in great detail at all of the land, including the oil field land, without going onto the property.”

The environmental assessment that Longcore oversees will also involve a herpetologist and mammalogists with the Natural History Museum, a bat expert, trail cameras to document animal species and their movements, particularly at night, and student employees who will sort through the images to identify the species in them.

The Baldwin Hills assessment will further employ mobile technology, such as smartphones and computer tablets, for collecting data onsite. Bat detectors will pick up the ultrasonic calls that bats make during evening flights and feeding activity, then transform those calls to audible frequencies and record the sounds to a mobile device or smart phone.

Volunteers using the detectors can upload the time and place of their observations along with the sound recording, and a bat expert will identify the species based on the call. Eventually, the project will produce a multi-platform map that will be available on those mobile devices.

“The agencies that support this work want to get the paper documents that are sitting on their shelves into the modern era of interpretation,” Longcore said. In the future, he predicts that smartphones and other mobile devices will be as useful as trailside signage for visitors to understand the Baldwin Hills.

“The Baldwin Hills as an open space is ‘the park that oil built,’ ” he said. “One reason it didn’t get developed is because of the industry that already was there.”

Baldwin Hills sits at the north end of the Newport-Inglewood Fault, which runs more than 40 miles from Culver City to Newport Beach. Many oil fields in the L.A. area are situated on this fault.

Directly beneath Baldwin Hills is the Inglewood Oil Field, considered one of the highest-producing reservoirs in L.A. County and one of the largest urban oil fields anywhere in the country. More than 1,000 wells have been drilled in the Baldwin Hills since the 1920s. The land around it was subdivided and covered with residential development after World War II. The Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area was later established on 400 acres of open land in Baldwin Hills in 1984.

When oil production appeared to slow down in the 1990s, government agencies made plans to create “One Big Park” to cover roughly two square miles, including the land used for pumping, existing public recreation areas and other parcels. The state created the Baldwin Hills Conservancy in 2000, and the Natural History Museum conducted an extensive survey of the natural resources within the conservancy’s proposed boundaries.

In the past 15 years, new petroleum reserves have been discovered in the Inglewood Oil Field, and drilling there might continue for 10 years or more. The “One Big Park” within the conservancy boundaries may be slow in coming. But the conservancy and the authority continue to work on plans to tie together different open spaces and recreational areas.

Nearly half of the lands are held by private landowners — primarily homeowners and petroleum interests — and the conservancy and the authority are working with both groups on conservation objectives.

“There’s a large community that has Baldwin Hills in its backyard. They use it, and we want to understand what’s there and communicate that to people so they can appreciate it and develop a sense of caring and stewardship for it.”