What would the ancient Greeks think of an Olympics with no fans?

Because of a dramatic rise in COVID-19 cases, the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2021 Olympics will unfold in a stadium absent the eyes, ears and voices of a once-anticipated 68,000 ticket holders from around the world. Events during the intervening days will likewise occur in silent arenas missing the hundreds of thousands of spectators who paid US$815 million for their now-useless tickets.

After 48 years teaching classics, I can’t help but wonder what the Greeks – who invented the Games nearly 3,000 years ago, in 776 B.C. – would make of such a ghostly version of their Olympic festival.

In many ways, they’d view the prospect as absurd.

In ancient Greece, the Olympics were never solely about the athletes themselves; instead, the heart and soul of the festival was the experience shared by all who attended. Every four years, athletes and spectators traveled from far-flung corners of the Greek-speaking world to Olympia, lured by a longing for contact with their compatriots and their gods.

In the shadow of dreams

For the Greeks, during five days in the late-summer heat, two worlds miraculously merged at Olympia: the domain of everyday life, with its human limits, and a supernatural sphere from the days superior beings, gods and heroes populated Earth.

Greek athletics, like today’s, plunged participants into performances that pushed the envelope of human ability to its breaking point. But to the Greeks, the cauldron of competition could trigger revelations in which ordinary mortals might briefly intermingle with the extraordinary immortals.

The poet Pindar, famous for the victory songs he composed for winners at Olympia, captured this sort of transcendent moment when he wrote, “Humans are creatures of a day. But what is humankind? What is it not? A human is just the shadow of a dream – but when a flash of light from Zeus comes down, a shining light falls on humans and their lifetime can be sweet as honey.”

However, these epiphanies could occur only if witnesses were physically present to immerse themselves – and share in – the spine-tingling flirtation with the divine.

Simply put, Greek athletics and religious experience were inseparable.

At Olympia, both athletes and spectators were making a pilgrimage to a sacred place. A modern Olympics can legitimately take place in any city selected by the International Olympic Committee. But the ancient games could occur in only one location in western Greece. The most profoundly moving events didn’t even occur in the stadium that accommodated 40,000 or in the wrestling and boxing arenas.

Instead, they took place in a grove called the Althis, where Hercules is said to have first erected an altar, sacrificed oxen to Zeus and planted a wild olive tree. Easily half the events during the festival engrossed spectators not in feats like discus, javelin, long jump, foot race and wrestling, but in feasts where animals were sacrificed to gods in heaven and long-dead heroes whose spirits still lingered.

On the evening of the second day, thousands gathered in the Althis to reenact the funeral rites of Pelops, a human hero who once raced a chariot to win a local chief’s daughter. But the climactic sacrifice was on the morning of the third day at the Great Altar of Zeus, a mound of plastered ashes from previous sacrifices that stood 22 feet tall and 125 feet around. In a ritual called the hecatomb, 100 bulls were slaughtered and their thigh bones, wrapped in fat, burned atop the altar so that the rising smoke and aroma would reach the sky where Zeus could savor it.

No doubt many a spectator shivered at the thought of Zeus hovering above them, smiling and remembering Hercules’ first sacrifice.

Just a few yards from the Great Altar another, more visual encounter with the god awaited. In the Temple of Zeus, which was erected around 468 to 456 B.C., stood a colossal image, 40 feet high, of the god on a throne, his skin carved from ivory and his clothing made of gold. In one hand he held the elusive goddess of victory, Nike, and in the other a staff on which his sacred bird, the eagle, perched. The towering statue was reflected in a shimmering pool of olive oil surrounding it.

During events, the athletes performed in the nude, imitating heroic figures like Hercules, Theseus or Achilles, who all crossed the dividing line between human and superhuman and were usually represented nude in painting and sculpture.

The athletes’ nudity declared to spectators that in this holy place, contestants hoped to reenact, in the ritual of sport, the shudder of contact with divinity. In the Althis stood a forest of hundreds of nude statues of men and boys, all previous victors whose images set the bar for aspiring newcomers.

“There are a lot of truly marvelous things one can see and hear about in Greece,” the Greek travel writer Pausanias noted in the second century B.C., “but there is something unique about how the divine is encountered at … the games at Olympia.”

Communion and community

The Greeks lived in roughly 1,500 to 2,000 small-scale states scattered across the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions.

Since sea travel in summertime was the only viable way to cross this fragile geographical web, the Olympics might entice a Greek living in Southern Europe and another residing in modern-day Ukraine to interact briefly in a festival celebrating not only Zeus and Heracles but also the Hellenic language and culture that produced them.

Besides athletes, poets, philosophers and orators came to perform before crowds that included politicians and businessmen, with everyone communing in an “oceanic feeling” of what it meant to be momentarily united as Greeks.

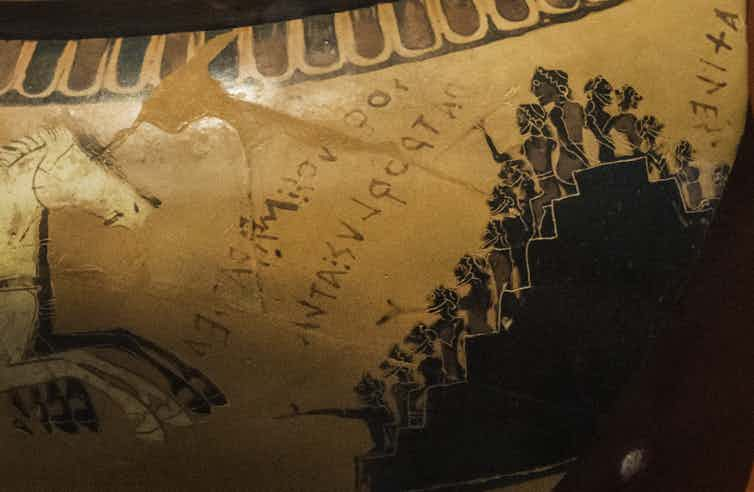

A detail of a Greek cauldron depicts spectators cheering on a chariot race. Egisto Sani/flickr, CC BY-NC

Now, there’s no way we could explain the miracle of TV to the Greeks and how its electronic eye recruits millions of spectators to the modern games by proxy. But visitors to Olympia engaged in a distinct type of spectating.

The ordinary Greek word for someone who observes – “theatês” – connects not only to “theater” but also to “theôria,” a special kind of seeing that requires a journey from home to a place where something wondrous unfolds. Theôria opens a door into the sacred, whether it’s visiting an oracle or participating in a religious cult.

Attending an athletic-religious festival like the Olympics transformed an ordinary spectator, a theatês, into a theôros – a witness observing the sacred, an ambassador reporting home the wonders observed abroad.

It’s hard to imagine TV images from Tokyo achieving similar ends.

No matter how many world records are broken and unprecedented feats accomplished at the 2020 games, the empty arenas will attract no gods or genuine heroes: The Tokyo games are even less enchanted than previous modern games.

But while medal counts will confer fleeting glory on some nations and disappointing shame on others, perhaps a dramatic moment or two might unite athletes and TV viewers in an oceanic feeling of what it means to be “kosmopolitai,” citizens of the world, celebrants of the wonder of what it means to be human – and perhaps, briefly, superhuman as well.

The ancient Greeks wouldn’t recognize some aspects of the modern Olympics.

Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]![]()

Vincent Farenga, Professor of Classics and Comparative Literature, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.