Alumnus’ software could help scientists beat coronavirus from home

While the coronavirus pandemic has made medical research an urgent priority, measures to prevent infections have shuttered labs and forced many scientists to work from home. Accessibility to 3D imaging, which scientists use to visualize data in robust ways, is now limited. The technology is generally only available within an institutional facility due to its high costs.

“3D imaging has played a key role in the creation and evaluation of most recent, clinically approved vaccines and medicines,” says Kyle McClary, who received a chemistry Ph.D. from USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences earlier this year. “But, in order to view 3D imaging datasets from home, a researcher needs software that can run $50,000 for a single user license. Even then, the current software only runs on advanced computers that cost thousands of dollars.”

McClary and John Paul “J.P.” Francis, who graduated from USC with a bachelor’s degree in computer science and business administration and is currently a Ph.D. student in computer science and chemistry at USC Viterbi School of Engineering and USC Dornsife, now offer a solution.

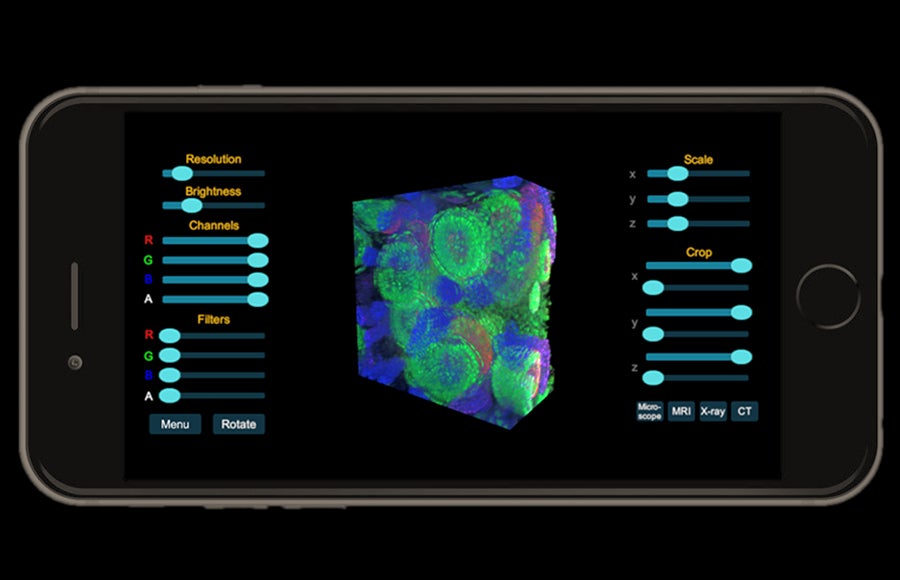

Their newly launched software Microscape allows researchers to view 3D imaging data on a home computer, cell phone, web browser, and even in virtual reality, no fancy hardware required. It also lets users collaborate remotely, enabling groups to log on and interact with the same 3D dataset simultaneously.

“It’s kind of like a Zoom meeting for sharing 3D imaging data,” explains McClary.

The Microscape beta model, launched on July 1, offers these capabilities to researchers for free.

A more advanced iteration of the software is available at a price thousands of dollars less than comparable software currently on the market.

Bridging art and science

Although a scientist by training, McClary is also drawn to the arts, writing music and making videos. “I’ve always been a hobby media maker and have always loved communication and storytelling,” McClary says.

While working on his Ph.D., he saw a listing for a grant from the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience looking to fund “convergent ideas,” projects that combine disparate fields such as biochemistry and cinematic arts, to solve challenging problems. He pitched an idea for a working group that could fuse art and science into singular projects, and after securing the grant, the Bridge Art + Science Alliance (BASA) was formed.

One of their first projects was Microscape. During BASA brainstorming sessions, McClary began to envision a virtual reality that could let scientists view biology from numerous angles, perhaps even wandering inside the structure of cells as if touring a house.

To execute this vision, McClary needed a collaborator with a solid understanding of VR. He attended a VR meet-up on campus where he met Francis and sold him on his idea.

Over the next year, the pair built Microscape on an open source gaming engine, a software platform used to build video games. This made Microscape much more affordable than image software from competitors. They employed 12 students from the USC School of Cinematic Arts and USC Viterbi School of Engineeringto work on animation, user interfacing and visuals.

Once Microscape was functional, Francis and McClary were eager to test the viability of the software in a real lab. The two connected with Francesco Cutrale, assistant professor of research in biological engineering at the USC Translational Imaging Lab. Cutrale agreed to test drive Microscape. He reported back with enthusiasm, touting the low price point, quality of the image rendering and potential for collaboration.

“Microscape can show you a three-dimensional object and have multiple people in the same room. That can facilitate the progress of science and create collaborations that would have not been easy to do previously. Now, we could collaborate with folks in faraway places, as long as they have an internet connection,” says Cutrale.

Into the future

McClary and Francis have applied for a provisional patent with help from the USC Stevens Center for Innovation and are working with the Alfred Mann Institute to formulate a business plan. Contracts with labs are in the works. The two hope to secure additional funding to scale up their business and offer the software to more labs around the world.

To Ray Stevens, Provost Professor of Biological Sciences, Chemistry, Neurology, Physiology and Biophysics and Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, founding director of the Bridge Institute at the USC Michelson Center and an advisor to both McClary and Francis, the software holds big potential. Stevens knows a thing or two about viable ventures — he’s started four biotechnology firms, including one that sold for more than $7 billion.

“The human body is incredibly complex and the old way of collecting, analyzing, integrating data with paper publications and static structures has hit its limits,” says Stevens. “What we need are new cinematic tools to integrate human biology data together. J.P. and Kyle have put together an amazing tool to do exactly this. I compare it to the invention of the GoPro, only at the molecular level.”