From free love to well-set table

Oneida. For most Americans the name conjures up fine silverware. Few are aware that behind this secular symbol of middle-class respectability lies the story of a 19th-century religious community endowed with radical notions of equality, sex and religion.

In Oneida (Picador, 2016), Ellen Wayland-Smith, assistant professor (teaching) of writing, traces this extraordinary history through the community’s founder, John Humphrey Noyes, from whom she is descended.

Noyes, the scion of a prominent Vermont family and a graduate of Yale Theological Seminary, founded his own offshoot of Protestantism, dubbing it “Perfectionism.” Like most Christians during this period, Noyes believed in the second coming. He also believed he was God’s prophet on earth. Amid the fervor of religious revival, he attracted a group of devoted followers seeking an alternative to Puritanism. In 1848, he established a revolutionary community in rural New York that aimed to achieve a sin-free life through God’s grace, while espousing equality of the sexes and encouraging sex with multiple partners via “complex marriage.”

“Oneida tells the story of how a communo-capitalist, free-love religious sect, over the space of a century, transformed into one of the country’s premier silverware manufacturers — Oneida Community Limited — the very picture of middle-class propriety and the white-picket-fence American dream,” Wayland-Smith said. “Oneida was very much a product of its time. In my book, I place the community in the context of the Second Great Awakening and the expansion of American capitalism, while highlighting Noyes’ incorporation of communism, utopianism, eugenics and spiritualism.”

An alternative lifestyle

Ellen Wayland-Smith, assistant professor (teaching) of writing, is a descendant of Oneida’s founder, John Humphrey Noyes.

While the idea of a Christian, Communist, free-love community sounds farfetched today, Wayland-Smith argues that Noyes’ vision was rooted in the larger American culture of the period.

“All these things that sound strange to our ears today were in fact up for grabs in the 1840s, an incredibly open time when almost anything seemed possible,” she said.

“Oneida was one of dozens of small, experimental communities that sprang up in the 1840s aiming to find alternative socialist living styles in reaction to their disgust at the way they saw America going in terms of a market economy, capitalism, industrialism and class.”

Ironically as the Community had emerged partly in protest against the Industrial Revolution, Oneida embraced manufacturing. Before the Community disbanded in 1879, the company began manufacturing spoons at their Wallingford, Conn., branch, laying the foundations of the 20th-century silverware giant, Oneida Ltd.

Early swingers

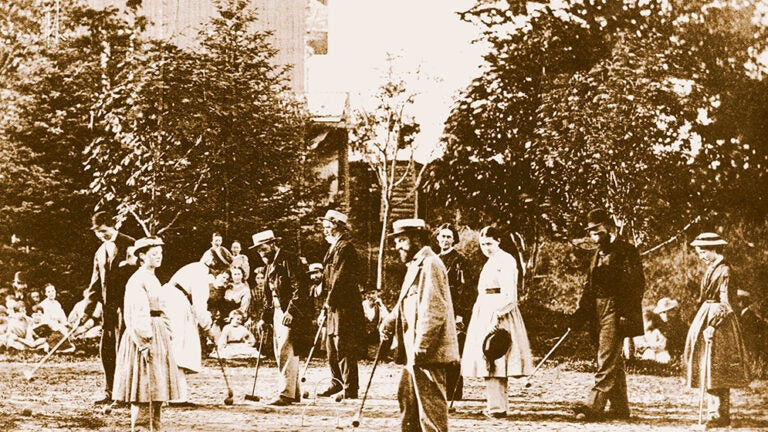

But if Oneidans were devout Christians and prosperous manufacturers who were often to be seen playing genteel games of croquet on their stately mansion’s manicured lawns, behind closed doors they pursued another, more controversial, aspect of community life.

Noyes’ sought to uproot selfishness from the human soul. That included not only giving up possessions, but also special attachments to people.

“Noyes saw marriage as a form of property ownership,” Wayland-Smith explained. “He believed that such feelings of selfish ownership prevented people from bonding together to form the body of Christ.”

The answer, Noyes determined, was a form of free love he dubbed “complex marriage.”

Ellen Wayland-Smith’s new book, Oneida (Picador, 2016), tells the story of how a radical religious community transformed itself into a successful silverware company and a symbol of middle-class respectability.

“This dabbling into complex marriage first occurred when Noyes and Mary Cragin, an original Community member, fell in love and embarked on a sexual relationship,” Wayland-Smith said. Soon Oneida’s founding group, which also comprised Noyes’ wife, Harriet, his sisters, their husbands and Cragin’s husband, George, were enthusiastically swapping spouses.

“They were swingers basically before swinging was ever invented,” Wayland-Smith said.

Close, but not too close

However, free love as practiced by Oneidans had its downside, as lovers were forbidden from becoming too close.

“If a couple became too attached to one another they would frequently be split up,” Wayland-Smith said.

“The reason they joined Oneida was because they thought selfishness was a primordial sin and they wanted to get rid of it so they spent a huge amount of time and agony trying to uproot from themselves any partiality.”

If all this sounds admirably self-sacrificing, Wayland-Smith discovered Noyes had another, less selfless angle. At Yale, he had fallen in love with his first convert, a girl named Abigail Merlin. When she married somebody else, Noyes wrote to her, saying that while on Earth she might be married to another, in heaven she was his spiritual bride. He eventually extended that, saying that all brides and grooms must share one another.

“So if you’re doing a psycho-biographical reading of how this free love idea came about,” Wayland-Smith said, “then, yes, it was because Noyes was obsessed with this woman who abandoned him, thereby leading him to develop this whole theory of spiritual wives.”

A secret history

Wayland-Smith grew up with Oneida, spending summers and Christmases at the 93,000-square-foot Oneida Community Mansion House, a rambling red brick colossus with more than 200 rooms.

Building on the Onedia Community Mansion began in 1861. Occupying 93,000 square feet and boasting more than 200 rooms, the rambling, red brick property is now a National Historic Landmark. Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection.

But if Wayland-Smith was familiar with the story of Noyes as visionary and benevolent socialist, many key aspects of her family’s history remained hidden.

“There was this whole other narrative that was unknown to me as a child,” she said. “My family were so ashamed of the lurid sexual aspect of the Oneida experiment they didn’t talk about it while I was growing up.”

It wasn’t until she began researching her book that she learned the full story.

“There was a controversial side of the family history that I unearthed that I’d never been told for obvious reasons,” she said.

Sinner or saint?

So was Noyes a madman or a saint? Wayland-Smith believes the question is open for debate.

“I think he was both. There are parts of Noyes’ theology that were beautiful and inspired. And there are parts that were creepy and sinister and self-serving. I came away from this project thinking you can’t ever say anything is just one thing. It’s always more complicated than that.”