The Science of Swimming

While studying exercise science as a master’s student at Long Beach State University, USC Head Swim Coach Dave Salo took a class in exercise physiology that changed the course of his career.

“I learned theories from Professor Joseph Mastropaolo that were intriguing — and completely contrary to what I knew as an athlete,” Salo said. “It piqued my interest in human performance.”

In one class the students were their own lab rats, testing Mastropaolo’s contrarian concept that to increase endurance in riding a stationary bicycle, the key is not to spin your wheels longer, but instead to ride for shorter amounts of time, pedaling faster.

“It was such an extreme notion that went against anything I had ever experienced as an athlete,” Salo said. “Usually coaches say, ‘Do more and you’ll get faster.’ He showed that if you do less volume working harder, you’ll increase your endurance.”

Salo, who earned a Ph.D. in exercise physiology from USC Dornsife in 1991, has built his career on Mastropaolo’s premise, coaching many Olympic swimmers to victory.

He is also the author of two books, Complete Conditioning for Swimming (Human Kinetics, 2008), co-authored with Scott Riewald, and SprintSalo: A Cerebral Approach to Training for Peak Swimming Performance (Swimming Support Syndicate, 1989).

Formulating hypotheses

Throughout his education at California State University, Long Beach, Salo was lucky enough to have subjects on whom to test his ideas.

“I was a coach at the Downey Dolphin Swim Club starting from my junior year in college,” Salo said. “I began to integrate the lessons I learned at school into my coaching.”

The scientific approach worked. “The kids were improving dramatically with my newly designed programs,” he said. “It was essentially a lab, and I was showing that my hypotheses were correct.”

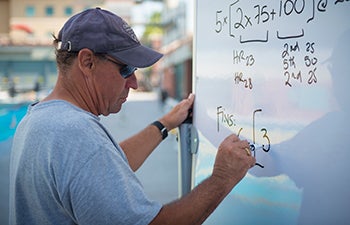

Dave Salo is in his 10th season as USC’s head swim coach.

After earning his master’s degree, Salo pursued a doctorate in exercise physiology at USC Dornsife.

“You earn a bachelor’s and think you have all the answers,” Salo said. “But then you go on to get a master’s and realize you have so many more questions — and so you get a Ph.D., not necessarily to find answers to all those questions but more to find the best strategies to answer the questions that keep emerging.”

During his time at USC, Salo conducted research first in the laboratory of Caleb Finch, ARCO-William F. Kieschnick Professor in the Neurobiology of Aging at the Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, assessing the effects of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) on brain tissue. He later transitioned to train under Kelvin Davies, James E. Birren Chair in Gerontology and professor of biological sciences, testing the effects of oxygen toxicity on gene expression.

Testing the waters

Salo also worked as an assistant coach under Peter Daland for the USC swim team while earning his degree and accepted a full-time coaching job in Irvine following graduation.

Irvine Novaquatics became a true test bed for Salo’s philosophy.

“On the first day of practice, I gave all the swimmers a lecture on human performance and exercise physiology,” he said. “I told them things were going to be very different.”

While some of his swimmers quit after learning about the changes, others put their trust in Salo’s scientific approach. Many who stayed excelled.

Salo led members of his team to a number of Junior National Team Championships and the United States Swimming National Championships. It was there he coached Amanda Beard, Aaron Peirsol, Jason Lezak, Gabrielle Rose and Staciana Stitts, who won a combined five medals at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia.

“From 1990 to 2006, we had more athletes make the Olympic team than any other club in the country,” Salo said. As a result of that success, he was recruited back to serve as head coach of the USC swim team.

“I was grateful to get this position because traditionally, to become head coach at a school like USC, one would have to coach another division-one college team first.”

Salo has published two books on his scientific approach to training competitive swimmers.

When he arrived, the USC athletes were largely receptive to his unique methodology — with the exception of some distance swimmers who were skeptical about how swimming less would lead them to victory in long races.

“They assumed that I was just a ‘sprint coach,’ so they were apprehensive,” Salo recalled. “But my first year, they were the ones who did the best. After that, they understood.”

Getting results

Salo makes sure never to stray from his roots as a scientist of human performance.

“There are the basic precepts that I employ that don’t change unless I see something that forces me to ask the question, ‘How can I make this better?’” Salo explained.

Sometimes his athletes challenge a component of his methodologies, and he makes sure to prove to them logically why it makes sense.

“It’s the lesson of a Ph.D.,” he said. “You have to justify what you tell your athletes to do. You have to be analytical and not spout out ideas you can’t defend.”

In addition to having the opportunity to coach some of the world’s most talented athletes, Salo appreciates USC for its wealth of intellectual capital.

“We are always looking for professors on campus who are doing work relevant to athletics — maybe it’s a sociology professor studying the dynamics of group structure or a psychologist who studies the mental aspects of sports,” he said. “My philosophy is always to take advantage of what’s available so that as we move forward, the team will just get better and better.”