Targeting Hearts

While growing up in California, junior Tiffany Lian traveled annually to her father’s homeland of Indonesia. It pained her to see her grandfather suffer from a chronic heart condition — which, after many years — left him too weak to fly to the United States for surgery.

“My grandfather had many operations in small hospitals where I knew the surgical techniques weren’t as advanced as they are here,” Lian said. “Seeing this always made me want to go into the health profession, especially cardiac medicine, and bring my knowledge to help people in other parts of the world.”

Still focused on repairing ailing hearts, Lian has broadened the scope of her ambitions to include pharmaceutical development, thinking that it may be possible, one day, for targeted medications to replace invasive surgeries. This summer the biochemistry major is conducting research in the laboratory of Raymond Stevens, Provost Professor of Biological Sciences and Chemistry.

“Kate White, the postdoctoral researcher I am working with, studies the bitter receptors,” she said. “It’s interesting because although they are called taste receptors, they are expressed in different parts of the body, such as the heart and lungs.”

Taste receptors belong to a family of proteins called G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which sense molecules outside of cells and activate cellular responses. GPCRs are important targets for pharmaceutical drug development.

“The problem is that we are targeting taste receptors with chemicals, but we don’t know what they look like,” Lian explained. “Much of my research is working to crystallize them to better understand the receptors’ exact structures. If you don’t know how a medicine is binding to a receptor, you don’t know exactly what reactions are happening, which could create side effects.”

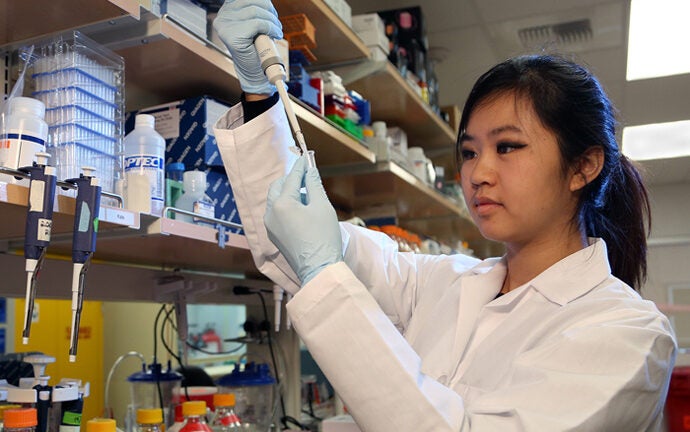

Lian’s passion for medicine stems from her frequent trips to Indonesia to visit her grandfather, who suffered from a heart condition. Photo courtesy of Tiffany Lian.

She has also started her own offshoot study of the sweet receptor — which scientists have shown is expressed in the brain.

“It’s exciting because it’s something I can call my own, meaning that if I’m able to publish a research paper, which is my goal, my name would probably be the first author on it,” she said.

Lian’s project is one of many ongoing investigations leading to pharmaceutical development in Stevens’ laboratory. Stevens joined USC Dornsife last year as director of The Bridge@USC, an initiative to unite the best minds in chemistry, biology, medicine, mathematics, physics, engineering, and nanosciences — as well as experts in such areas as animation and cinematography. Together, the researchers aim to build the first virtual model of the human body on which to develop safer and more effective treatments for a wide range of diseases.

Another important component of the initiative is to introduce USC undergraduates to convergent science, or the idea that a single problem needs to be addressed by professionals in many different fields.

“We generally think about physics, biology and chemistry as being completely separate departments,” Lian said. “But when I was talking to Professor Stevens initially, he told me that in this position I would get exposure to all of these different areas within the sciences — even computer modeling.”

Stevens’ description of his collaborative ethos resonated with Lian’s vision for her future in research.

“You can go in the lab and one postdoc has a degree in biochemistry while the person at the next station has a degree in physics,” Lian said. “Yet they are always talking to each other about the same problems. They have a common goal — to cure diseases.”

Lian plans to continue working in Stevens’ laboratory during the fall semester, earning course credit for directed research. She is still earning the required credits she would need to apply to medical school, with the intention of keeping the door open to pursue a career as either a surgeon or a biochemical researcher.

“I love that you can’t come into this job thinking you can do what someone else has done and succeed,” she said, adding that she hopes other undergraduates will follow her lead and apply for research positions.

“I think it’s important to learn how to think outside of the box, which is part of what research teaches you,” she said. “You’re not just learning from a textbook. You’re putting what you’ve learned in a real-world, hands-on application while discovering new ideas.”

More than anything, though, she is excited that her efforts now have the potential to effect lasting changes.

“I hope to graduate knowing that I contributed,” she said. “Even if just in a small way.”