In Memoriam: Sarnoff Mednick, 87

Sarnoff Mednick, professor emeritus of psychology at USC Dornsife, has died. He was 87.

Mednick died on April 10 in Toledo, Ohio. He suffered from Parkinson’s disease and dementia.

Mednick was the first scientist to revisit the genetic basis of mental disorders after the backlash against genetics resulting from the era of eugenics. A pioneer of the prospective high-risk longitudinal study to investigate the causes of such disorders, his emphasis was on schizophrenia, but he also made significant contributions to the study of creativity, psychopathy, alcoholism and suicide.

“Sarnoff will be especially remembered for his paradigm-changing work on perinatal risk factors for schizophrenia and crime and the initiation of the Mauritius Child Health Project that has continued for nearly five decades,” said JoAnn Farver, professor and chair of psychology at USC Dornsife. “His former graduate students and postdoctoral researchers will remember his inspiring mentorship that set them on highly successful career paths.”

Laura Baker, professor of psychology at USC Dornsife, said Mednick influenced the lives of many students, colleagues, friends and family.

“He was a brilliant scientist and wonderful mentor, and he inspired many to pursue important societal questions which were not always fashionable at the time, but which often led to pivotal changes in thinking about the roots of human behavior,” she said. “Sarnoff’s students remember him for his insouciant optimism and unstinting generosity, and for always insisting that science must combine both high standards of methodological rigor and great intellectual fun. He was loved by many and will be missed greatly.”

Mednick joined USC Dornsife in 1977, working as a professor of psychology and later directing the Social Science Research Institute until his retirement in August 2008.

A trailblazer who was not afraid of controversy, Mednick’s years at USC were notable for the creativity and risk-taking in his research. His lifelong research record reflected a talent for finding the “undiscovered piece” that served to move a field forward.

In a groundbreaking psychology study published in Science in 1984, Mednick showed that criminal behavior has a genetic component. At the time, criminologists still rejected the possibility of any genetic influences on crime. However, by using an adoption paradigm, Mednick showed that although there was no correlation between criminal conviction in adoptive parents and their children, there was a correlation between convictions of biological fathers and their offspring. The role of genetics in crime and other behavioral outcomes is now well recognized and accepted by researchers and the general public.

Mednick’s research also focused on perinatal risk factors as predictors of the development of schizophrenia and violence in later life. Critics struggled to believe that factors so disconnected in time from outcomes could be relevant to risk. However, Mednick found that prenatal exposure to influenza predicted both schizophrenia and affective disorders, and that delivery complications in combination with early maternal rejection significantly increased the risk for criminal violence.

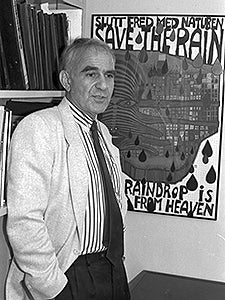

Beloved by his students, Mednick taught at USC Dornsife for 31 years. This photograph was taken in 1987. Photo by Irene Fertik, courtesy of the USC University Archives.

Mednick received international recognition for his work on these topics. He prioritized the dissemination of his findings to developing countries through NATO conferences he organized in Tuscany, Italy, throughout the 1980s and ’90s, thereby profoundly influencing the thinking of a new generation of scientists.

“My father always said there was no greater job in the world than being a professor,” said Mednick’s daughter, Sara Mednick. “He made it feel like the most exciting and adventurous and stimulating job in the world. He loved working with his students. I am now a professor and to see him at work with his students was one of my greatest inspirations.”

Mednick’s daughter, Lisa Mednick Powell, said her father instilled in her an improvisational approach to life and work.

“By the time I was 15, he had taken my sister Amy and me on many adventures, including trips to Yugoslavia, Mauritius, Israel and Denmark,” she said. “His work is characterized by a certain fearlessness and a refusal to be stymied by borders imposed by others. This quality most certainly informed my life as an artist, musician and teacher.”

The son of Jewish parents who had immigrated to the United States from Ukraine, Mednick was born on Jan. 27, 1928, and raised in the Bronx in New York City. His mother Fanny Bronstein Mednick, a former factory worker, was a homemaker and his father Harry Mednick worked in his uncles’ hat- and cap-making business during the day and as an insurance salesman at night, later training as a television repairman.

Mednick earned a B.A.from the City College of New York in 1948, followed by a master’s degreefrom Columbia University. In 1954, he earned his Ph.D. in psychology from Northwestern University.

He completed his postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Chicago before taking up an appointment as an instructor at Harvard University. From there he moved to the West Coast, becoming a visiting assistant research professor at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1958-59. It was here that he studied creativity and carried out interviews with mathematicians, architects and scientists about their creative processes. This research formed the basis of the Remote Associates Test of creativity (RAT), a measure developed in 1962 and still widely used today.

“Sarnoff’s Remote Associates Test is a lasting contribution to the psychology of thinking and creativity,” said Stephen Madigan, associate professor of psychology at USC Dornsife. Madigan remembered accompanying Mednick to Hollywood in 2013 as he administered the RAT to 25 young adults who worked as writers for television comedies.

“Sarnoff had suggested that ‘humor professionals’ ought to have very high RAT scores. Indeed, their scores were about 1.5 standard deviations above the mean of bright young undergraduates,” Madigan said. “That afternoon was typical of time spent with Sarnoff and his wit, insight, breadth of knowledge and the pleasure of his company.”

In 1959, Mednick joined the University of Michigan, rising from assistant professor to professor to special research fellow. In 1968 he became a professor at the New School for Social Research in New York, where he taught until 1977.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Mednick began designing and conducting seminal longitudinal studies in Denmark and Mauritius.

Deeply interested in the congenital origins of schizophrenia and armed with the knowledge that genetic factors increased the risk for schizophrenia by a factor of 10, Mednick still faced the difficulty of how to effectively carry out longitudinal work on an outcome that was quite rare in the general population. He found the solution in Denmark, a country with population-level mental health records and the means to trace subjects across generations.

In 1962, Mednick developed the Copenhagen High Risk Project, focusing on children of mothers with schizophrenia as a high-risk group. The study followed participants until they were 42, yielding important data concerning the role of prenatal factors and structural brain deficits in the risk for schizophrenia. Similar methodology was later used for the study of depression and bipolar disorder, and variations are now state-of-the-art methods for studying autism spectrum disorders.

Mednick established an influential and longstanding research presence in Denmark, founding the Psykologisk Institut in Copenhagen and serving as its director from 1962-92. He was awarded the honorific degree of Dr. Med. by the University of Copenhagen in 1976.

Following the success of the Copenhagen High Risk Project, and with the support of the World Health Organization, Mednick initiated the Mauritius Child Health Project in 1972. This project created specially designed nursery schools where three-year-olds were given an environmental enrichment that included better nutrition.

These children were followed to adulthood, yielding unique data on the role of nutrition in the development of schizotypal personality and antisocial behavior. Mednick’s work in Mauritius is reflected in current studies of complementary medicine, including food supplements and probiotics as preventative agents for negative health outcomes.

The author of more than 300 peer-reviewed publications, Mednick earned many prestigious honors, most recently the Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Science of Psychology from the American Psychological Foundation. He also received a National Institute of Mental Health Career Development Award, the Leiber Prize for Outstanding Achievement in Schizophrenia Research from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the Joseph Zubin Award, a lifetime achievement award given by the Society for Research in Psychopathology.

Mednick is survived by daughters Amy Mednick and Lisa Mednick Powell (from his first marriage in 1950 to Martha Schuch); son Thor Mednick and daughter Sara Mednick (from his second marriage in 1967 to Birgitte Reinholdt); grandchildren Violet Alaynick, Frederick Mednick, Sam Kastner and Sophie Kastner; and brother Edward Mednick.

He will be cremated at a small private ceremony at the Newcomer Funeral Home in Toledo, Ohio, on April 24. A memorial will be held in Los Angeles at a later date.

USC Dornsife’s Department of Psychology has established the Sarnoff A. Mednick Memorial Fund to support a Sarnoff A. Mednick Memorial Lectureship. The annual award will recognize individuals whose work exemplifies the genetic and biological bases of psychopathology in general, and in the areas of schizophrenia and/or crime in particular. For further information, please contact JoAnn Farver, professor and chair of psychology, at farver@dornsife.usc.edu.