Defying the Labels

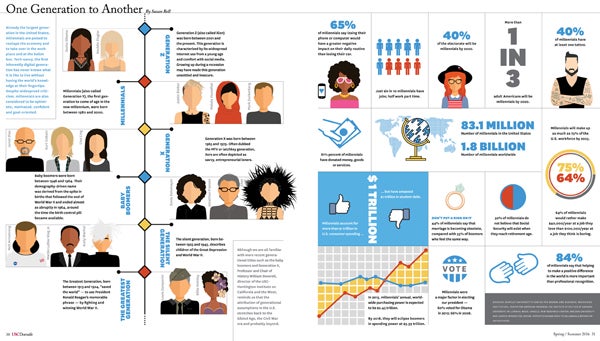

The biggest generation since the boomers, U.S. millennials — those born between 1980 and 2000 — are the most technologically advanced and racially and ethnically diverse group in history. They are arguably also the most maligned, frequently depicted by older generations as disengaged, social–media–obsessed job hoppers with an insatiable thirst for constant validation. Are these characterizations justified, or are millennials just misunderstood?

“I think it’s very easy to stereotype and dismiss millennials in this way because so much of their lives are tied to social media, and this is also a trope that popular TV shows generally rely on to characterize the millennial generation,” said Jody Agius Vallejo, associate professor of sociology.

“But it’s also very easy to contradict these stereotypes when you actually stop looking at millennials as a homogenous or monolithic population and start examining heterogeneity within the millennial population,” she added.

William Deverell, professor and chair of history and director of the USC-Huntington Institute on California and the West, concurs but said generational stereotyping is nothing new.

“We’re familiar with the greatest generation, baby boomers, generation X and now millennials, but generational assumptions probably existed in the broader culture in the 1920s, the Gilded Age and even as far back as the Civil War era,” he said. “Some of these generational definitions speak to a certain nostalgia and incorporate naïve, if understandable, assumptions that the past was simpler than the present. And that’s never true.”

While Deverell agrees that generations can be roughly identified by certain cultural predilections, he suggests that assumptions about generational identity may also reveal a lot about the generations doing the identifying.

“I believe we oftentimes write our greatest fears and ambitions on the lives of those who aren’t us,” he said. “So in some respects we might actually be holding up a mirror.”

So let’s hold up a mirror now to those whom Time magazine dubbed “The Me Me Me Generation” and take a critical look at the various epithets so widely used to describe them. And while we’re at it, let’s get a glimpse of how that criticism sheds light onto their parents — the original “Me Generation” — the baby boomers.

Lazy

In a 1992 study by the nonprofit Families and Work Institute cited by Time, 80 percent of people under 23 wanted one day to have a job with greater responsibility; 10 years later, only 60 percent did.

It’s one of the most persistent criticisms directed at millennials, yet no one could accuse USC Dornsife alumnus and entrepreneur Adam Goldston of being lazy. With his twin brother, Ryan, Goldston worked tirelessly to bring their Athletic Propulsion Labs (APL) high-end sneaker to market after launching the company in their dorm room. This year, the brothers made Forbes “30 under 30” list for their achievements in retail and e-commerce. They now employ 15 people — almost all millennials — while their shoes are sold around the world in upscale retail outlets.

Goldston believes older generations’ perception of millennials as lazy stems from how technology has revolutionized traditional business practices.

“When we started the company, my dad said, ‘Go to the office every single day, from 9 to 5. Get into a routine, you don’t want to be seen as lazy,’ ” remembered Goldston, now a globetrotting business executive. “Since then the world has changed dramatically. Now I spend more time out of the office than I do in it. The old guard doesn’t necessarily realize that the same thing you can do sitting at a desk, you can achieve anywhere today on a cell phone.”

Goldston notes another reason his generation might be perceived as lazy by older generations is their preferred work environment. The APL office boasts a pingpong table and mini-basketball hoop, and employees pump up their adrenaline or let off steam with Nerf gun battles in the hallways.

The selfie generation is accused of narcissism but many millennials defend their social media obsession, arguing that they are the most connected and technologically adept generation yet.

“From the outside looking in, older people may not take some of the things we do seriously, but they contribute to the company dynamic,” Goldston said.

“Ryan and I didn’t come up with our initial idea by being constrained to old-guard thinking. We were students who got our big idea playing basketball. So I think a lot of the great ideas we and our employees have come to us when we’re doing fun things.

“When we’re 60, it will probably be hard for us to under-stand what the 20-year-old culture is like then, too,” Goldston added with a laugh.

USC Dornsife Board of Councilors member and alumnus Martin Irani is chair of USC Dornsife’s Gateway Internship Program, which aims to prepare undergraduates for their careers by offering paid summer internships and mentoring from distinguished professionals. His experience with millennials, both through the program and as vice president of Hancock Park Associates, a private equity firm, has given him insight into another misunderstanding that can lead to misperceptions of millennial laziness — their rejection of traditional business rules in favor of working faster and, in their opinion, smarter and more efficiently.

“Millennials want to do things the way they’re used to doing everything — fast. But, to older generations it makes millennials seem lazy because they don’t want to take the long route,” Irani said.

“Millennials need to slow down,” he added, “be a bit more deliberate and thorough, and be willing to take on any task they are asked to do, even if it’s menial, because they won’t be perceived as team players if they don’t.”

Job hopping

Millennials are often denigrated for being “job hoppers.” The median tenure for millennials is 24 months compared to seven years for a baby boomer. But Irani, who earned his bachelor’s degree in economics in 1987, followed by an MBA from USC Marshall School of Business in 1991, notes that old taboos surrounding the practice are no longer valid.

“The world has changed since I was younger, when changing your job often was seen as a negative,” said Irani, who also serves on the board of the USC Alumni Association. “Now it’s more acceptable and you see millennials switching jobs every two years.”

Goldston believes one reason millennials switch jobs so frequently is because they care so much about their day-to-day work experience. That’s another reason his company fosters a fun work environment. “As millennials, we want to enjoy every aspect of our lives. So when people come to work for us, we want to make it enjoyable, not an arduous task.”

Irani offers this tip to older generations who want to motivate millennial employees to stick around longer. “Millennials need to feel they’re making a difference. Older people need to show them what they’re doing is important to the community. If the company has a purpose, millennials may stay longer.”

To avoid friction with older generations at work, Irani advises millennials to seek their advice, spend time with them, listen to their stories and give them respect. “Don’t dismiss the older generation just because they don’t do Snapchat,” he tells Gateway participants. “They have other gifts to teach you that are just as valuable.”

Entitled

Millennials received so many participation trophies growing up that a recent study, cited by Time, showed that 40 percent believe they should be promoted every two years, regardless of performance. Statistics like this feed into the cliché of millennial entitlement.

But one need look no further than USC, and in particular to first-generation students, to explode such stereotypes, noted Vallejo. Her research investigates the mechanisms that facilitate social and economic mobility, and entry into the middle and upper classes, for Latino and Asian American youth. Those mechanisms include policies, access to education, mentors, and family and community wealth.

“Many first-generation students come from low-income or working-class families and they’re anything but entitled — or narcissistic, lazy or self-centered,” she said. “As education costs have increased, not only are they working long hours in addition to their studies and extracurricular activities, they’re also taking on a significant amount of debt and working numerous jobs to support their education and themselves and contribute to the family income.”

Adrian Trinidad, who earned his bachelor’s degree in sociology in December 2015, was among about 3,500 first-generation students at USC. Growing up in a Los Angeles neighborhood plagued by drugs and gangs, Trinidad, at the age of 10, became the primary caregiver for his father, who was diagnosed then with schizophrenia. His mother began working up to 15 hours a day to support the family.

“Growing up in that environment gave me a vital sense of strength and perspective, and also helped me value every opportunity I get. I know how to be humble, but also validated for my own achievements and those of my family and community,” said Trinidad, who will begin his Ph.D. in urban education policy at USC Rossier School of Education in the Fall.

“I remember going to a movie theatre to collect aluminum cans so my family could have a meal, and seeing my friends there with their families,” he said. “That hit me really hard. I realized I was in a different position from them because I was trying to support my family in any way I could. My childhood experiences made me mature and grow at a very young age and I had to work harder to get to where I wanted to be.”

Alex Culley, a graduate student in applied psychology whose research focuses on millennial engagement in media, agrees, noting that his generation has no desire to settle for what their parents had.

“We want to be fulfilled,” Culley said. “For us, happiness isn’t about getting a job, working at it for 30 or 40 years and retiring with a gold watch and that’s it. Does that mean we’re entitled? Maybe in some sense that’s true. But to say millennials are not engaged politically, or not hardworking, isn’t accurate.”

Narcissism: The pros and cons of the Selfie Generation

According to the National Institutes of Health, the incidence of narcissistic personality disorder is nearly three times as high for those in their 20s as for the generation that’s now 65 or older.

Like many experts and millennials themselves, Morteza Dehghani, assistant professor of psychology and computer science, blames social media for the perceived increase in narcissism and resultant need for validation among millennials.

“We scroll through feeds and click on likes based on how people present themselves. This trains our brains to focus more on surface features rather than judging people on the relationships we have with them. It’s very superficial and shallow, and it makes us crave the same sort of constant attention no matter what we’re doing. All of us are becoming affected. And millennials, because they grew up with these platforms, are more affected than others.”

Goldston, however, takes issue with how narcissism has been linked with social media.

“Social media didn’t exist 15 years ago, so people didn’t have to worry about how they were perceived by the world. Now if you post anything online, you know you’re going to be viewed and judged. So I don’t think it’s a narcissistic view; I think it’s a conscious view.”

Disney channel actor and musician Laura Marano is a freshman majoring in politics, philosophy and law. As a social media maven who has chalked up more than 7 million likes and followers on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, she sees the upsides and downsides of these and other social media channels.

She concedes that social media use springs from a desire for attention but says that it is not necessarily linked to narcissism.

“I think it’s less about narcissism and more about utter insecurity and trying to convey some sort of image that others will like,” she said. “Social media makes people very vulnerable.”

Arguing that every generation is faced with something the generation before has not seen, Marano said millennials are doing exactly what they need to be doing: reacting to this huge societal and cultural shift that is social media.

“We’re finding our identity and how it relates to this new change of social media, and in fact we’re not doing as terrible a job as everyone says,” she said. “I think everyone needs to give us a bit of a break here.”

Deverell notes that the degree of connectivity fostered, supported and demanded by social media among millennials not only marks a profound difference from previous generations, but obviously also brings its own burdens.

“It comes with an awareness of the great scale of the global community and the great challenges of a worldwide sensibility of creation, obligation or opportunity, and that’s difficult to shoulder when you’re a young person emerging from your teens into young adulthood.”

Vallejo also defends millennials’ love affair with social media, reminding us that they are the most connected, technologically adept generation yet.

“The stereotype of the selfie generation, the idea that millennials want to be famous, or that they revere reality TV stars, or model those behaviors, is just that — it’s a stereotype,” she said. “We have to remember that social media is natural to millennials; they grew up with it. It’s something they use not just to create social networks but also as a medium for social justice and civic engagement.”

Disengaged Slacktivists?

Indeed, when millennials engage on social issues they tend to do so principally through the Internet. Social media can effectively spread information and rally followers around a cause, but millennials’ reliance on it has given rise to accusations of so-called “slacktivism,” where people share a status or use a hashtag and feel they’ve done their part.

Marano believes this trend rises from feelings of insignificance in such a vast and heavily populated world.

“Millennials are engaged and love to spread awareness about what’s going on, but social media has made them more acutely aware of how small they are in this huge world,” Marano said. “That makes them less inclined to believe that if they donate money or time it’s going to create actual change.”

Culley, however, said he feels the slacktivist label is not representative.

“I know there are lots of hardworking people in my generation who break those stereotypes,” he said.

Vallejo agrees, citing USC Dornsife alumna and first-generation student Christina Wilkerson, who graduated with a bachelor’s in sociology in 2012. “She attended Columbia School of Social Work and she uses social media and digital storytelling to create community for black youth,” Vallejo said. “She was a Fulbright finalist for research in the Caribbean who uses social media and digital storytelling to investigate the role of religion in women’s rights.”

Elizabeth Shaeffer, a senior majoring in political science and sociology, admits her generation is constantly on social media but she also defends the practice. “I know a lot of people argue that we’re disengaged with those around us, but I think in fact we’re more engaged.”

Shaeffer recently participated in a research-based internship through USC Dornsife’s Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics with advocacy firm RALLY and its client California Parks Now. Using social media, she and her fellow interns sought to increase funding and encourage activism and awareness among millennials for parks in California.

Of course, not all millennial engagement takes place over social media. Vallejo said her research on middle-class Mexican Americans and Latino elites and her experience mentoring numerous first-generation college students at USC show that many millennials retain an ethos of giving back to family and the community, and to remedying social and economic inequality.

“These cases completely contradict the one-dimensional negative stereotypes about millennials,” she said.

Vallejo points to the Black Lives Matter movement, the DREAMer movement, and the ongoing rebellion on college campuses by many millennials who have been staging sit-ins, protests and walk-outs to champion increased diversity in higher education.

“Let’s not forget that 44 percent of millennials are non-white,” she said, and they’re demanding greater diversity among universities’ faculty and staff.

“We can’t say there isn’t still a sense of fighting for equality and rights in a way that’s been a common thread throughout American history.”

Deverell finds millennials’ regard for egalitarian points of view regarding racial, sexual and gender identity inspiring. “Their vision on this is to be applauded,” he said. “It’s not perfect, but this generation has much to teach us about our visions of one another and how we can, and ought to, build community, regardless of difference.”

But while Culley, who was raised in a moderately affluent family, notes that there are student governments at every university around the country that are active and involved, he also admitted that he’s familiar with millennials who aren’t politically or civically active.

“I know many people who simply aren’t engaged because they feel they’re not listened to, and I think that’s a perception that’s been propagated by older people in this country,” he said. “It’s a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy.”

As for her generation’s alleged unwillingness to rebel, Maria Jose Plascencia, a senior majoring in American studies and ethnicity and the daughter of a single mother who is a restaurant worker in Tijuana, Mexico, put it down to general contentment with the status quo.

“We’re not as brave as previous generations and I think that comes from feeling we don’t have as much to lose because we’re at a privileged point in history,” said Plascencia, who plans to earn a Ph.D. in history.

‘Helicopter parenting’

Much of the blame for millennials’ allegedly needy and entitled behavior has been laid at the feet of their baby boomer parents, widely accused of overparenting, over-scheduling and overpraising their offspring.

Vallejo notes that in the last few decades there has been a shift in parenting among middle- and upper-class parents. These so-called “helicopter parents” adopted what celebrated sociologist Annette Lareau termed “concerted cultivation” in an attempt to foster their children’s prospects.

“As a result, many youth today from middle- and upper-class backgrounds have an enormous skill set that allows them theoretically to compete and have an advantage in middle- and upper-class social and economic spaces that some other students haven’t had the opportunity to experience,” said Vallejo. “However, sometimes it can be difficult when they come to college and their parents aren’t there to solve their problems. That’s why college can be an extremely important growth experience for many students.”

Shaeffer, who said her middle-class parents consciously chose not to be helicopter parents, has a certain sympathy for those students whose parents opted to follow that child-rearing style.

“If you’ve been in an environment where you’re constantly told where to be and what to do, when you get to college the freedom must be almost overwhelming,” she said. “If this is your first take at deciding whether to go to the movies with friends or study for that exam, then it’s much harder to make the right decision than if you’ve already tested that out in high school and experienced the consequences.”

Vallejo stressed that millennials from less affluent backgrounds are less likely to have been raised by helicopter parents.

“It’s a different parenting model from that occurring in lower-income or working-class families who engage in what Lareau calls ‘natural growth,’” Vallejo said.

“Students who grow up in low-income or working-class families have a very different appreciation for the opportunities they are given or experience because they don’t see them as something that should be automatic. Students from lower-class and disadvantaged families are often more entrepreneurial because they frequently have to figure things out for themselves.

“Those kinds of responsibilities translate into all other aspects of their lives. They don’t have that sense of entitlement, and I think that’s very important for people to understand when thinking about the millennial generation.”

New challenges in an uncertain future

The rise of technology and student debt, and an uncertain economy, mean that millennials have to face additional pressures that their baby boomer parents did not.

“We have to live up to these ideas that we should be millionaires at 18, that we should invent an app and strike it rich, and that puts a lot of unfair pressure on our generation,” Culley said. “These are all pressures that didn’t exist before the Internet, or not to this extent.

“Many millennials feel they were dealt a bad hand. It’s hard to find anyone of my generation who doesn’t believe in climate change and who isn’t scared by it on some level.”

Trinidad agreed.

“Millennials are more outspoken than other generations, and they have a right to be because they’re the generation that’s the most educated and the most underpaid,” he said. “For the previous generation to criticize this generation is faulty because they didn’t face the same challenges we do to secure a job and an education. Being outspoken is necessary and justified. I don’t think it should stamp us as a group that’s needy, narcissistic and demanding. That’s unfair.”

Goldston believes much of the criticism of millenials stems from older generations’ resistance to change.

“Change is uncomfortable but it’s a necessity. Whether or not current or older generations like it, things are going to evolve,” he said. “Millennials are setting the tone for what the future’s going to be because we’re going to control it.”

Deverell stressed the importance of looking beyond caricature and name calling in generational conversations.

“Older generations may say, ‘We created this world for you, why are you taking it for granted?’ and millennials may respond, ‘Yes, you created this world for us and it has so many problems.’ Yes, the world that’s being inherited now is utterly described by limits and finite boundaries of opportunity, resources or nature, but that’s true across generations. It’s not simply the generations that are coming of age that are frustrated by that. Those challenges can bind us together, too, out of a need to engage with not just one generation, but two or three or four, in order to solve these problems.

“Let’s not forget that the world millennials are stepping into is not a world they created,” Deverell concluded. “My suspicion is that they will change that world significantly, and my hope is that it’s for the better.”

Vallejo agreed, noting that because they represent so much variety in terms of place, ethnicity and class, millennials bring a multitude of experience and solutions to key issues affecting our society.

“Millennials are civically engaged, optimistic and concerned about social and economic issues,” she said. “Older generations tend to lament changes they see occurring in attitudes and behaviors among the younger generation, but many millennials are striving to change society for the better. Instead of dismissing millennials, that’s something older generations need to validate.”

Illustrations by Justin Renteria for USC Dornsife Magazine

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Spring-Summer 2016 issue >>