George H.W. Bush understood that markets and the environment weren’t enemies

Former President George H.W. Bush, who died on Nov. 30, was admirable for many reasons, from his skillful leadership through the end of the Cold War to his personal warmth and courtesy. As an environmental economist, I believe his approach to conservation also deserves attention.

Bush majored in economics at Yale and was a skilled politician. He believed that market-based solutions could protect the environment at lower cost than the command-and-control strategy that was more typical in the 1970s and 1980s.

Under that approach, regulators ordered each polluter to install the same equipment to reduce emissions. This could be cost-effective if all polluters used the same technology, but in modern economies, firms rarely have similar management or the same operating equipment. Bush was willing to test the idea that setting pollution reduction targets and letting regulated firms decide how best to achieve them could lead to better outcomes.

Markets for clean air

In June 1989, Bush proposed what would become his most important environmental achievement: the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. This sweeping legislation used a market-based approach to halve sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants, which reacted in the air to produce harmful acid rain.

This pollution was generated mainly by coal-fired electric utilities in the Midwest, but winds carried it into New England and mid-Atlantic states, where it damaged forests, rivers and lakes. States where the pollution was produced had little incentive to regulate it because the costs were borne by others far away. In a 2011 study, Nobel Laureate William Nordhaus and others estimated that coal-fired power plants generated social costs – including acid rain – that could equal or exceed the value of the electricity they produced.

President Bush followed the advice of economists who recommended introducing a national market where utilities could buy and sell the right to pollute. This approach made sense for mitigating acid rain because utilities differed with respect to their cost of reducing emissions. Utilities in states such as Ohio had much higher emissions, and a greater scope of emissions reductions possibilities if they were required to cut them.

President George Bush presents a pen he used to sign the Clean Air Act Amendments to EPA Administrator William Reilly, left, Nov. 16, 1990 as Energy Secretary James Watkins looks on. AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi

President George Bush presents a pen he used to sign the Clean Air Act Amendments to EPA Administrator William Reilly, left, Nov. 16, 1990 as Energy Secretary James Watkins looks on. AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi

Under the legislation, each utility would receive an allotment of permits, proportional to its past emissions, that allowed it to release a fixed amount of pollution. The total number of permits was set at a level that would reduce national emissions by 10 million tons relative to the 1980 level, phasing down over time. Each company could use its permits to cover its emissions, or sell any permits it did not use at the market price. If a utility could reduce its emissions for less than the going market price for a permit, it could make those reductions by whatever means it chose, then sell the permit and keep the difference.

This approach encouraged utilities to hire environmental engineers to update their production processes and find cleaner strategies, such as switching to lower-sulfur coal. It created dynamic innovation investment to discover new strategies for producing power while creating fewer emissions.

The legislation passed the Senate 89 to 10 and the House 401 to 25. Such bipartisan support for environmental regulation is rarely seen today. “Every city in America should have clean air,” President Bush said as he signed it. “With this legislation I firmly believe we will.” And studies show that he was right: The program successfully reduced sulfur dioxide emissions at a lower cost than the command-and-control method.

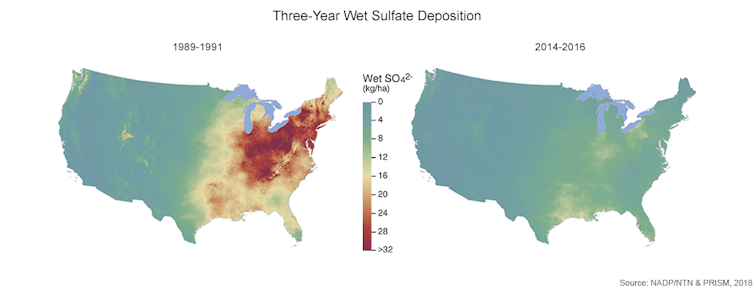

Wet sulfate deposition fell by 66 percent across the eastern U.S. from 1989–1991 to 2014–2016, thanks to reduced sulfate emissions. EPA

Wet sulfate deposition fell by 66 percent across the eastern U.S. from 1989–1991 to 2014–2016, thanks to reduced sulfate emissions. EPA

Can emissions trading save Earth’s climate?

Today climate change is the world’s biggest environmental challenge. Bush took this problem seriously enough to issue an order in 1989 that led to creation of the U.S. Global Change Research Program, which produces expert reports on how climate change is affecting the United States. In 1992 he signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which created a process for countries to work together to understand and respond to climate change.

It’s hard to know whether Bush would have taken steps to curb climate change if he had been reelected in 1992. Some members of his administration supported such a course, but others were less convinced of the need to act. And critics found fault with positions Bush took on other environmental issues, especially in the second half of his term.

Nonetheless, Bush succeeded in building a political coalition to reduce pollution, and I believe there are valuable political economy lessons to be learned from his record as debate continues over future U.S. climate mitigation policy.

As our nation’s population and per-capita income continue to grow, making progress toward sustainability will require reducing the emissions our economy generates per dollar of income. The acid rain program showed that markets for pollution lower the cost to society of achieving this goal. By rewarding economic actors who can reduce pollution at the lowest cost, they give businesses an incentive to become even better at this task.

President Bush speaks on U.S. climate change policy at Georgetown University, Feb. 6, 1990.

As concerns grow over inequality in America, U.S. officials also must pay close attention to who bears the costs of new regulations. If carbon mitigation policies raise electricity and gasoline prices, then middle-class purchasing power could decline.

But this income effect can be offset by simultaneously imposing a carbon fee and then giving households a lump-sum rebate. This approach would adhere to President Bush’s core goals of harnessing market forces to accelerate environmental progress while protecting the pocketbook of the middle class. Prominent liberal and conservative economic experts who have served under every U.S. president since Nixon support this approach.

President Trump plans to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Accord, the latest stage of international efforts to curb climate change, and has repeatedly questioned whether climate change is real. In contrast, President Bush spoke of it as a challenge to be faced. Just after signing the Framework Convention on Climate Change, Bush stated in a speech to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro:

“We must leave this earth in better condition than we found it, and today this old truth must be applied to new threats facing the resources which sustain us all, the atmosphere and the ocean, the stratosphere and the biosphere. Our village is truly global.”

Matthew Kahn, Professor of Economics, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.