What driving ambulances taught a sociologist about inequality

On the outskirts of a large California city, a woman lies in the back of an ambulance, having been severely beaten during an assault. She struggles to breath as the vehicle speeds toward the hospital. A paramedic hovers over her, trying to insert a tube through her mouth and down her throat to deliver oxygen to her lungs, but her throat is too swollen and the tube won’t go down.

The worried paramedic looks up at the EMT driving the ambulance: “I can’t intubate her, she’s not breathing very well. It’s up to you to get us to the trauma center as fast as you can.”

Josh Seim sat in the driver’s seat. Still a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley at the time, he was researching his dissertation, which focused on the labor of ambulance crews. But he hadn’t stopped at mere observational fieldwork — he’d also trained to become an EMT himself.

Which is how he found himself whisking this woman to her fate at the local hospital late that evening.

The persistent professor

Seim, now assistant professor of sociology at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, traveled a winding path to become an ambulance-driving academic. Growing up in Spokane, Washington, a career as a professor seemed an unlikely future. His mother was a hair stylist and his father stocked frozen food at a grocery store. Like both of his parents, Seim dropped out of high school and got his GED diploma.

Seim then enrolled at a community college where he struggled initially.

“I failed a political science class, failed a geography class, and then I was put on academic probation,” he said. A sociology class righted his course. “It was a combination of being really motivated not to fail a class and also having an instructor who was passionate about sociology.”

After that success, he was eager for more on the subject.

“I asked the community college teacher, ‘How do you do what you do?’ And she said, ‘You have to get a Ph.D. in sociology.’ I didn’t even know what that meant. I had to Google it.”

He transferred to Gonzaga University to complete his undergraduate studies and while there applied to graduate programs. He was first accepted to a master’s program at Portland State University, where he graduated in 2011. He was then accepted to the University of California, Berkeley as a doctoral candidate.

He arrived at Berkeley without a specific research focus for a dissertation. He’d gotten kicked out of his initial field site, a prison in Oregon. Seim had been studying incarceration and reentry issues there, and had planned to continue this work while at Berkeley. A good deed ended the project.

“The prison staff got mad at me because I had given a recently released prisoner a ride home,” Seim said.

His memories of a conversation with a parolee about transitional housing sparked a new research idea. The parolee told him ambulances visited the facility frequently. “I thought, ‘Why is the ambulance always there?’” says Seim.

He looked into the research around ambulances. “There was stuff about workplace culture, but it wasn’t really speaking to the urban inequality literature that I was interested in. So that compelled me to pursue it more.”

Ambulance chaser

Seim embarked on fieldwork at an ambulance company headquartered in an unnamed California county. (The county remains unidentified to maintain the anonymity of Seim’s research subjects.) He intended to focus on the trauma cases that ambulance crews worked on, but he quickly discovered this was not the right approach.

The paramedics and EMTs he shadowed laughed at his emphasis on “trauma work.” It’s not that they didn’t respond to serious trauma calls in the city. They did, but just not as often as they responded to less serious, non-trauma calls. He learned that serious trauma cases were rare enough to be desirable, and workers actually competed for the most traumatic emergency calls.

“If you’re in the ambulance bay and you’re listening to dispatch, if somebody hears a gunshot call that’s two blocks away, the crews will literally fight with one another because they want that one,” says Seim.

What was frustrating for these workers were the calls that they felt fell outside their scope, which made up the majority of their outings. Ambulances now attend to all the human ills of urban life, often with little training or resources. Workers who had gone into the field to tackle medical emergencies instead became tasked with complex, chronic issues faced by the mentally ill, elderly and unhoused who lack a robust public safety net.

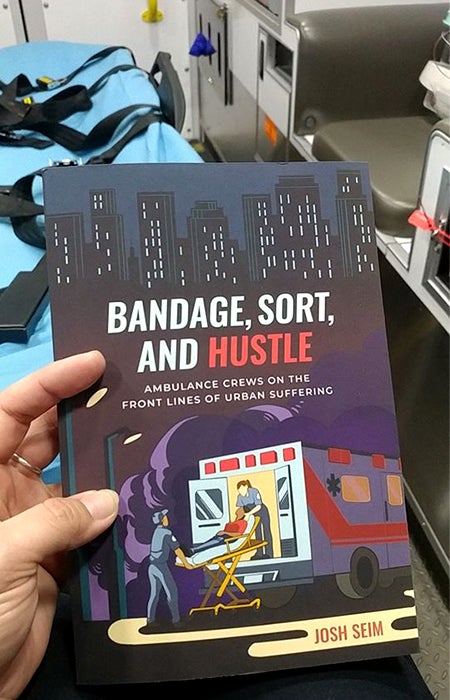

Seim’s book Bandage, Sort, and Hustle: Ambulance Crews on the Front Lines of Urban Suffering (University of California Press, 2020).

These folks often become “super users,” calling ambulances again and again for primary care, transport and mental health treatment, to the chagrin of the EMTs and paramedics who are poorly equipped for these social work requests.

Ambulance companies are also precariously financed and thinly stretched. Many communities rely on privately run outfits, like Seim’s, which compete against one another for operations contracts and are pressured to complete as many billable hospital transports as possible. Some insurance plans pay little for rides, and uninsured patients often can’t cover the bill.

Seim threw out his original dissertation plan and began again. He focused instead on the role ambulance workers played in a system ill-designed to meet the needs of the vulnerable. He completed ride-alongs with paramedics and EMTs and took meticulous notes of his observations. He shadowed ambulance supervisors and attended management meetings. He analyzed thousands of ambulance medical records. He also took EMT training to familiarize himself with the work of his research subjects.

Then, his wife lost her job.

When he told the managers and workers at the ambulance firm, they offered an unexpected suggestion. “I said, ‘I don’t think I’m going to be able to do this research much longer. I think I’m going to have to go back and teach.’ And they said, ‘Well if you want to be here, you should just become an EMT.’”

A siren call for change

After nearly two years in the field as both observer and ambulance worker, Seim returned to Berkeley and finished his Ph.D. dissertation in 2018, which he recently published in book form as Bandage, Sort, and Hustle: Ambulance Crews on the Front Lines of Urban Suffering (University of California Press, 2020).

For Seim, what emerged from his time in the field was a pressing need to utterly revamp ambulance services, from the way rides are funded to the workers inside.

“I think we need to eliminate the fee for service, and I think this necessitates something like Medicare for all,” he said. “Something where everybody has insurance and these operations are run in such a way that they can’t take advantage of those public benefits.”

Staffing differently could also be of benefit to all involved.

One option would be to “eliminate the role of the emergency medical technician and replace them with a social worker,” he said. “You can keep the paramedic doing all the deep clinical work and then have the EMT be trained as a social worker, or a social worker with EMT certification.”

The goal shouldn’t be to simply dissuade “super users” or those dealing with chronic illnesses from calling 911, but to have ambulances and their workers better suited to meet the needs of these complex calls.

“My third recommendation is to strengthen the welfare state so that people don’t have to call the ambulance,” Seim continues. “Things like Medicare for all, guaranteed housing programs and guaranteed work programs: These are things that would minimize the number of people that would be in such desperate and suffering positions where they would have to summon an ambulance.” An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Seim’s perilous rush to the hospital with the assault victim was actually his final call. Shaken by the intense experience, he called out sick for the remainder of his schedule and never picked up another ambulance shift.

“I feel like I was in a privileged position to be able to walk away when things got hard. A lot of my friends who work on ambulances, they face those cases frequently, and most of them don’t have the opportunity to walk away or call in sick like I did,” he says.

Despite his support for overhauling how ambulances serve urban areas, the workers’ unwavering commitment in moments of crisis made a big impact on Seim. To him, they are deeply committed to what they see as “legitimate” ambulance work, a devotion which transcends a mere job.

One evening during training, Seim and his crew were five minutes away from clocking out after a long shift. A call came through with news of a shooting two blocks away.

“The people training me said, ‘Okay, we’re going to stay late today.’” They volunteered over the radio to take the call and extend their shift.

“We ended up staying an hour and a half late. We chose to,” Seim said. “We could have just sat back, let another crew take it, got off work on time after 12 hours, but we were motivated to do this everyday hero type thing.”