Why are so many Los Angeles landmarks turning 100 this year?

Many of Los Angeles’ most iconic buildings and monuments are celebrating their 100th year.

The centennials demonstrate the 1920s’ outsized impact on the city.

The ’20s were a boom time for L.A. thanks to the simultaneous rise of oil, real estate, entertainment and aircraft industries.

Much of L.A. still retains the shape of this period.

In 1920, a seemingly innocuous event occurred: Los Angeles surpassed San Francisco in population for the first time. The difference wasn’t very large by today’s standards, just 70,000 more residents, but it was a sign of things to come.

Up until then, San Francisco had been considered the leading city west of the Mississippi, thanks to the Gold Rush of 1849, which had transformed it from a sleepy hamlet of 200 to a bustling metropolis of 25,000 in just two years. By the end of the 1920s, however, L.A.’s population would double in size and snatch San Francisco’s position as the West Coast’s fastest growing city.

“1920 was the breakout year for Los Angeles, when L.A. really sped up,” says Phil Ethington, professor of history, political science and spatial sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Science. He is at work on the forthcoming book Ancient Metropolis: The Los Angeles Region and its Place in Global History, from the Pleistocene to the Present. “The reason for all this is that the city’s business leaders were very ambitious. Starting in the 1890s, they began organizing infrastructure with the plan to make it the biggest city on the West Coast.”

Alongside infrastructure, like the controversial Los Angeles Aqueduct erected in 1913 to quench the thirst of the city’s growing population, key industries also emerged during this period. By the 1920s, sports arenas like the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and sumptuous hotels like the Biltmore were rising all across the basin. They formed the city we still see today when we close our eyes and envision L.A.

Oil and stars

L.A.’s star rose partly due to its participation in four cutting-edge industries, says Ethington.

The first was oil. In 1892, Edward Doheny (the same Doheny whose name graces a USC library) drilled the first productive well near the current site of the Echo Park Swimming Pool off of Sunset Blvd. Soon oil jobs, or the prospect of digging for your own fount of liquid gold, lured tens of thousands west and made a few men like Doheny wildly wealthy. By the 1920s, a sprawling web of wells across the city helped to make California the country’s most productive oil state.

Just down the street from rows of steadily bobbing oil pumps, another powerful industry was on the rise. By the 1920s, movie-making had congealed in L.A., where filmmakers like Cecil B. DeMille and Jesse Lasky had discovered the area’s versatility as a stage set.

“They realized that Los Angeles was the ideal place to make movies, with 300 cloudless days a year and all the landscapes in the world that you could ask for: mountains, deserts, forests, lakes and beaches,” says Ethington.

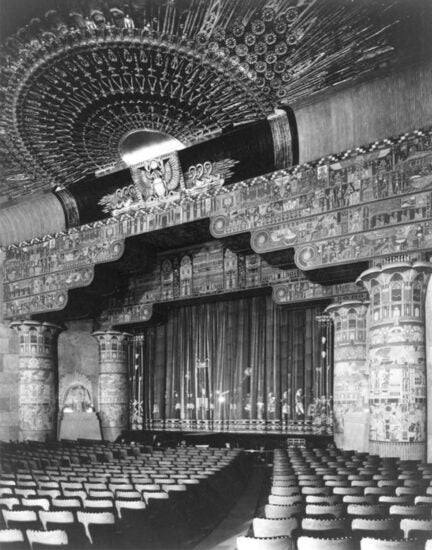

Thousands of skilled laborers, along with aspiring actors, actresses, screenwriters and other creative talent, flowed into the city to take part in this latest iteration of show business. Thus, you’ll find a number of theatres hitting 100 right around now. The Egyptian Theatre opened in 1922, the El Capitan in 1926 and Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in 1927.

One other new industry was also on the ascent, thanks to the push of those ambitious city businessmen. Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Otis Gray and his son-in-law Harry Chandler backed engineer Donald Douglas’s new aircraft plant, which opened in Santa Monica in 1921. Douglas Aircraft would eventually churn out tens of thousands of planes for World War II and subsequent conflicts.

La La Land

Alongside these emergent industries arose one more — land.

Part of the real estate boom was tied in to these new economic drivers: Arriving workers needed places to live and those making it rich wanted sprawling estates.

There were also more romantic reasons, worked to great advantage by real estate boosters. “Movies were set in Los Angeles, and people knew that stars like Lillian Gish and Charlie Chaplin lived here,” says Ethington.

The mild weather was also an advantage, he adds. “It was relatively easy for real estate promoters to sell the lifestyle of Southern California, it’s ideal climate and Mediterranean environment: ‘Here are orange groves and night-blooming jasmine, which you can smell all night long.’”

As new neighborhoods sprung to life, roads were laid to keep the swiftly growing expanse connected. Mulholland Highway was tarred down the spine of the Santa Monica Mountains. Broad surface streets like Western, Vermont and Figueroa were stamped across the basin, replacing dirt roads, which had thus far persisted well into the new century.

“Of course, the oil was ready at hand for supplying gasoline to the automobiles,” says Ethington. It’s no surprise that the historic Auto Club building, former headquarters of the Automobile Club of Southern California, celebrated 100 years in January. Cars don’t get all the glory though: Los Angeles’ bus system also hits its centenary this year.

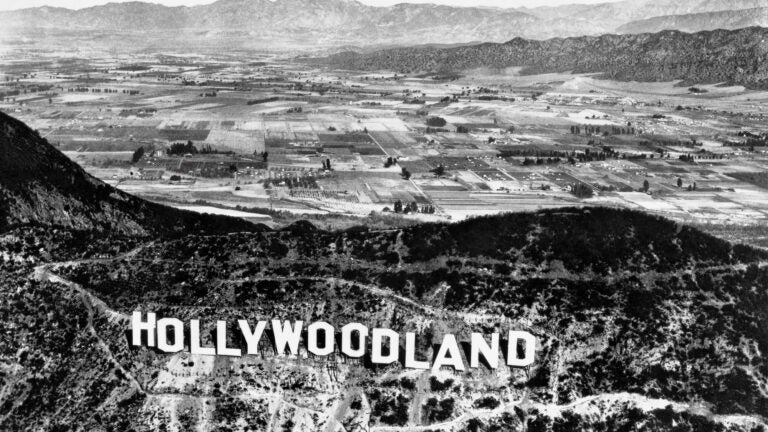

Many of L.A.’s most iconic neighborhoods arose during this real estate boom. In 1923, a massive sign reading “HOLLYWOODLAND” sprung up on the hillside above a new housing development, a sign that eventually became synonymous with the entire city itself.

“The 1920s is really the foundation of what most Americans think of when they think of the Los Angeles landscape and way of life,” says Ethington. “Los Angeles still bears it’s stamp.”