Why Classics?

Classics explores the civilizations of the ancient Mediterranean world in all their extraordinary ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural diversity. Because the discipline takes as its subject entire cultures, students gain experience working with a rich variety of sources in art, literature, philosophy, music, theater, and politics, and opportunities to engage with a range of modern academic fields. Such great breadth of perspective makes classics one of the most all-encompassing and flexible of humanities disciplines. Study of the classical languages, Latin and Greek, moreover, can help students develop linguistic and analytical skills valuable in a range of professional pursuits — and both satisfy USC’s foreign language requirement! While majoring or minoring in classics might make you a better lawyer, doctor, investment banker, or web designer, as with all humanities disciplines, study of the ancient Mediterranean world has unlimited potential to make you a more thoughtful, articulate, and critically astute human being.

The goal of the course is to offer a better understanding of the ancient world through social analysis. How did humanity go from hunting and gathering to building cities and empires and what kind of consequences did it have for human beings? The course will focus on the Near East, Egypt, Greece, Rome and Han China and compare state formation at different places over time. It aims at developing historical thinking but intersects with the social sciences. Some of the readings and lectures will introduce students to tools in historical sociology, political science, geography and demography used by some ancient historians. These approaches provide complementary viewpoints to understand why and how ancient societies developed particular political, religious, military or economic institutions and how these institutions shaped the lives of individuals differently.

The course introduces students to (1) the culture, society, literature, religion, and politics of the ancient Roman world, and (2) the many ways in which this world this world has been used, interpreted, and reimagined in later periods. In addition to surveying key events, institutions, and cultural changes in Roman history itself, from its beginnings to late antiquity, we will examine both how and why Rome has inspired, haunted, and perplexed so many people for over a millennium since its supposed “fall,” and continues to do so today.

Our readings will span genres (historiography, philosophy, poetry, ethnography, biography, autobiography, and epistles), geographies (Rome and the Italian peninsula, North Africa, Northern Europe, China, and Latin America), and time periods (antiquity itself, the Middle Ages, the early modern world, and finally, the 21st century). Although by no means comprehensive, our texts and accompanying lectures will offer case studies or snapshots of how Rome has been invoked, imitated, and challenged. Taken as a whole, this course will offer an examination of what it means for the past to have a “legacy”: that is, how it has been received, appropriated, revived, and at times distorted, at various other moments in history. As a component of the GE-B curriculum, it will therefore interrogate one of humanistic inquiry’s most fundamental concerns: the complex interplay between past and present, both in our own lives and those of others.

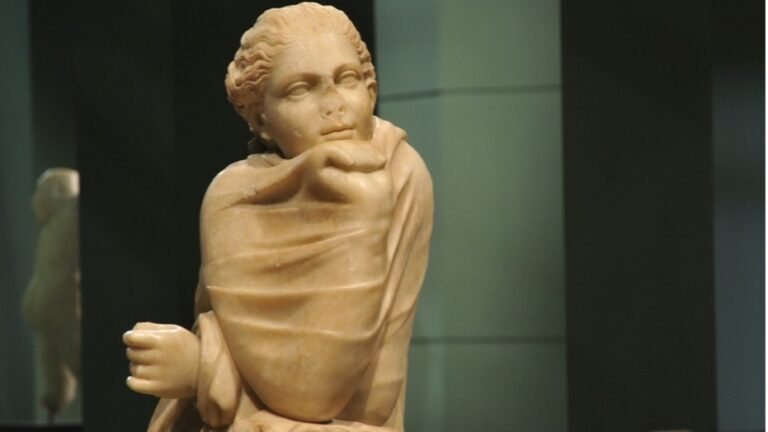

This course examines humans’ multifaceted relationship with the natural environment in cultures of the ancient Mediterranean world. In a wide-ranging survey of sources in literature, art, philosophy, and the history of science, students will consider the diverse, interconnected ways in which the cultures of antiquity perceived and made sense of the natural world— from early cosmological thought in Mesopotamia and Greece to the rise of rationalist investigations of nature in philosophy and the physical sciences, to the expansion of geographical writing, to the wondrous literary topographies of epic poetry, tragic drama, pastoral song, and myth, to divine presences in nature experienced in cult and ritual, to the rich traditions of visual representation of the natural world in painting, sculpture, and beyond, and much else.

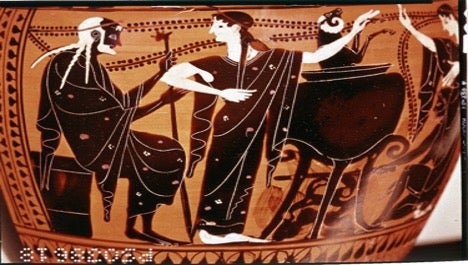

This course introduces the mythology of classical Greece, with attention to other contemporary and ancient traditions. Mythology is often understood as stories about the gods and heroes, and stories about creation. We will be reading a wide selection of such stories, considering the cultural and political implications of myth as well as the question of what it might mean to live a mythological life.

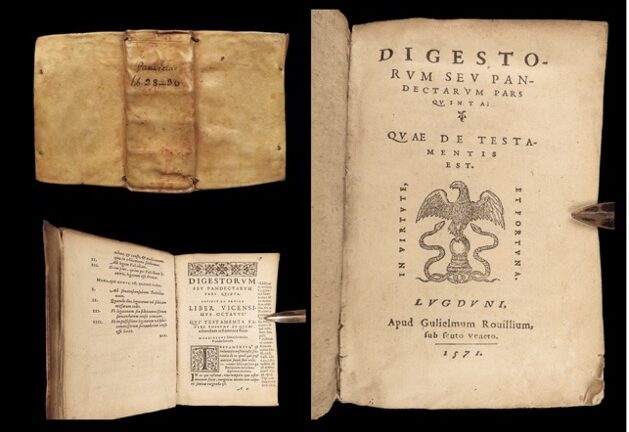

In European and American culture, Roman law has a unique position: unlike other legal systems, it had an impact not only in the ancient world but also in medieval and modern times. It included norms as well as interpretations of the law by jurists (jurisprudence), whose controversies and discussions are a wonderful source for social history.

The first part of the semester will be dedicated to the historical development of Roman law and jurisprudence (during ancient and medieval times), together with a brief overview of the main areas of legal doctrine and on the sources of law. We will use Peter Stein’s Roman Law in European History (available online)

The second part will focus on family law case studies. We will first look at the basic concepts of persons and family, then we will concentrate on some interpretations of the law of marriage, of slavery, of property and delicts. We will mainly use Bruce Frier’sThe casebook on Roman Family Law (available online)

This course is a study of four Roman poets – Virgil, Ovid, Seneca and the author of the historical drama Octavia – and their reactions to and critiques of the new imperial Rome. Attention will be given to the transformation of Rome by Augustus and the Julio-Claudian emperors who followed him, but the main energy of the course will be directed to the critiques of that transformation in pastoral, epic, elegy and drama. Particular works – Virgil’s Eclogues and Aeneid, Ovid’s Fasti, Seneca’s Troades and the anonymous Octavia – will be studied, and sections of them read closely and examined in detail. Such examination will address the traditional topics of literary form, structure, diction, tone, imagery and meaning, but will also consider such wide-ranging issues as: pastoral values and cultural norms; the authority and ambivalence of epic; elegy as counter-cultural verse; tragic catharsis and political action/inaction; Roman monuments and political power; self-reflection in literature and art; inter/intratextuality and literary semiotics; civilization and cultural forms; censorship and the poet; poetry/art and cultural memory/erasure; theatre and metatheatre; metatheatre as cultural mirror; myth as history/history as myth; myth as social and political critique.

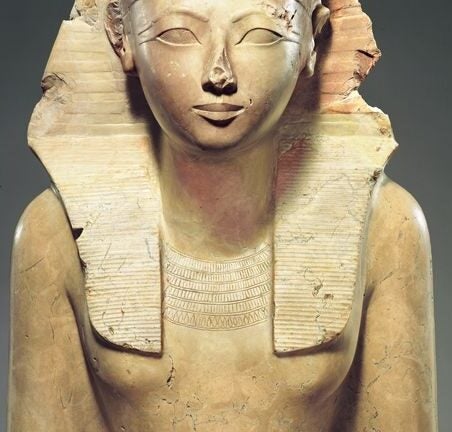

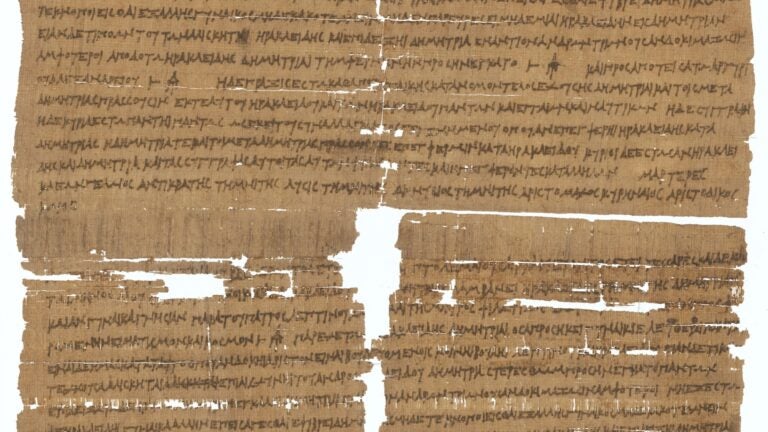

Alexander the Great’s conquest transformed the geopolitics of the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the fourth century BC. What impact did this conquest have on the Egyptian state and its society? The purpose of this class is to introduce students to the history and culture of what is called Ptolemaic Egypt after the name of Alexander’s general, Ptolemy, who secured Egypt for himself and his descendants (305-30 BC) until the death of Cleopatra VII and the annexation of Egypt by the Roman emperor-to-be, Augustus (30 BC). Students will engage with texts (in translation) written more than two thousand years ago by ordinary people and with archeological material and coins found in Egypt to analyze a vast range of topics: immigration, ethnic interactions, religion, warfare, taxes, and land tenure, trade and monetization of the economy, as well as scientific, philosophical and literary achievements connected to the new intellectual capital, Alexandria, and its famous library.

Poetry and philosophy in Rome from Ennius to Lucan

In this course we will explore interactions of poetry and philosophy in Roman culture, with particular attention to the hexametric tradition. We look both at philosophically inspired poetry and at prose that cites, engages with, comments on and repurposes poetical texts for philosophical discourse.

We begin with the fragments of Ennius’ Annales, and consider his allegiance to Pythagoreanism, his mysterious endorsement of the atheist philosophy of Euhemerus, his relationship with Empedocles, as well as the Stoic leanings of some of his fragments. Unsurprisingly, we spend a large portion of the course reading Lucretius, with particular attention to his approach to atomic theory (DRN 1-2), love (3), death (4), the social evolution of human societies and human progress (5). We then consider the philosophical make-up of the Aeneid from three not-so-common points of view. Leaving aside the somewhat trite question of Virgil’s allegiance to Stoicism, we focus on Virgil’s interaction with Posidonius’ theory of decline, with the poetry of Lucretius, and with philosophical visions of the end of the world. From here we move to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. We read the beginning and the end of the poem and consider its interconnections with Empedoclean thinking, Lucretius, and Pythagoreanism. We make a stop-over in the Tiberian period to read the Stoic inspired didactic poem on the cosmos by Manilius. From this we move to the Neronian period to consider Seneca’s reception of Ovid within a Stoic framework in his prose works, as well as select scenes and topics from Lucan’s Stoic epos on the civil war. If time permits, we will have a few bonus tracks on late antique poetry, with particular attention to the pagan epics of Claudian and the Christianpoetry of Prudentius.

The focus of the course is on the close reading and analysis of selected imperial Latin texts, with attention to the particularities and semiotics of their language and structures and to their dynamic interaction with (a) their contemporary political, social, intellectual, cultural and material context and (b) the evolving and increasingly complex Latin literary system. Methodological and theoretical issues are examined as they arise.

Prof. A. M. Yasin (yasin@usc.edu)

Through constant processes of decay and destruction—whether slow or fast, natural or human-caused—individual buildings and whole cities deteriorate, and always have. Yet beyond the fact of material break-down lies a wide range of cultural responses to ruins—from their erasure through restoration or their preservation as memorials, to their “conversion” into new, useable spaces. Ruins, as materially fragmented former structures, are generally set apart from every-day, quotidian spaces and as such can become freighted with special status: as marginal or dangerous sites outside the normal order, as material witnesses to past peoples or events, or as palpable access points to numinous powers.

This course examines how ruins, as cultural artifacts, have historically been made, and *un*made. Looking at the long “lives” of cities through a critical lens, we will investigate the ways in which (and by whom, to what ends) past buildings have been coded with different values in ancient, post-classical, and modern times—from squalor and symbols of social decay, to historical evidence or memorials of loss, to useful raw material. We will explore how these competing values and their change over time shape how built environments evolve, and we will consider social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of our own society’s responses to ruins.

In the first part of the course, we will examine the institutions and technologies through which the Western tradition of ruins has been created and sustained. Our focus will be on representations of material remains in various ancient and modern media (text, painting, photography) and the institutions that have shaped them (e.g. war, religion, archaeology, conservation). The class will then turn to examine strategies for “unmaking” ruins, returning them to the every-day, through material and political interventions from antiquity to today. While we will primarily focus on the post-construction fates of ancient structures in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean, readings and discussion will also engage with critical questions raised by ruins of other civilizations and of more recent pasts (e.g. architecture of subaltern groups, shrinking urban centers, and post-industrial environments).

* course approved for elective substitution for the Visual Studies Graduate Certificate (contact VSGC graduate advisor Jennifer Miller, jennifmm@usc.edu)

Greek 120 is the first component of the introductory Greek sequence. In this class, students will be introduced to the basic elements of Ancient Greek grammar and syntax with a focus on the Attic dialect. Over the course of the semester, the emphasis will be on developing reading proficiency. To this end, students will gain experience translating Greek sentences and passages adapted from various Greek authors as well as composing their own sentences in Greek.

Greek III reviews Greek grammar and focuses on reading selections from ancient authors, esp. Plato.

In this course we will be focusing on Homer’s Iliad and the Odyssey, two of the most influential cultural products of Ancient Greece. We will have the opportunity to discuss a number of important topics reflected in Homeric epic, which pertain to the cultural, social, and political context of the Greek society of the Archaic, and to some extent of the Classical period, such as (but not limited to): the sociocultural function of the art of poetry and story-telling, the Homeric conception of heroism, the role of women in epic, the central institutions of hospitality and guest-friendship, as well as the imaginative ways in which the Greeks conceived of their gods and the nature of the relationship between the human and the divine.

For questions contact Dr. Afroditi Angelopoulou (manthati@usc.edu)

This course will introduce you to the essentials of Latin grammar and vocabulary, with the ultimate goal of providing you with the ability to read, write, and translate Latin texts. Over the course of the semester, we will explore Latin vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and pronunciation. In addition, this course will include discussions of various aspects of Roman history and culture (such as literature, visual art, and religion).

This course, building upon LAT 120, will continue your introduction to the essentials of Latin grammar and vocabulary, with the ultimate goal of providing you with the ability to read, write, and translate Latin texts Over the course of the semester, we will explore Latin vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and pronunciation, with the aim of reading and translating original Latin texts in the final few weeks of the semester. In addition, this course will include discussions of various aspects of Roman history and culture (such as literature, visual art, and religion).

Latin 222 is the third and final component of the introductory Latin sequence. Over the course of a semester, students will review grammar and strengthen skills fundamental to translating Latin. Additionally, students will swiftly advance beyond the “synthetic Latin” of the grammar-book and gain their first experiences with “Latin in the wild”. To achieve this end, we will read short pieces and excerpts from the unedited prose and poetry of various authors writing Latin during Rome’s Republican and early imperial period.

Helpful Links

Please view the USC Catalogue for a complete list of courses offered by the Department of Classics and the Schedule of Classes for current and upcoming scheduled courses.