Introduction

During the second millennium B.C.E. the Hittites, a group of people who spoke an Indo-European language established an empire, Hattusa, centered in north-central Anatolia (the Asian part of modern-day Turkey). The empire reached its height in the 14th century B.C.E., but by the 12th century B.C.E. had broken up into a number of independent Neo-Hittite city-states. By the beginning of the first millennium B.C.E., a number of the Neo-Hittites states were being overrun by “roaming” Aramean tribes who spoke a Semitic language, Aramaic.

Accounts from the ninth century B.C.E., mainly Neo-Assyrian, depict the Aramean tribes either wrestling with Luwian/Hittite kings for their territories or joining together with them in an effort to stave off the Assyrian conquest. In the famous battle of Qarqar in 853 B.C.E. a coalition of Neo-Hittite and Aramean kings, which also included king Ahab of Israel, formed an anti-Assyrian alliance against Shalmaneser III.

It was about this same time, the mid-ninth century, that the Aramean kings began to produce their own written records, though few would survive. Unlike Assyrian and Babylonian cuneiform, the Arameans wrote with an alphabet used mainly on papyrus or animal skin. Such perishable materials can survive only in the most arid climates such as that of Egypt or Judean desert, but not in the rainier regions where the Aramean kingdoms emerged. Therefore little of Aramaic literature from before the Persian period has survived except for those inscribed on stone in funerary and architectural monuments. The monumental inscriptions of these early Aramean kings make up the bulk of Iron Age Aramaic Literature.

Language

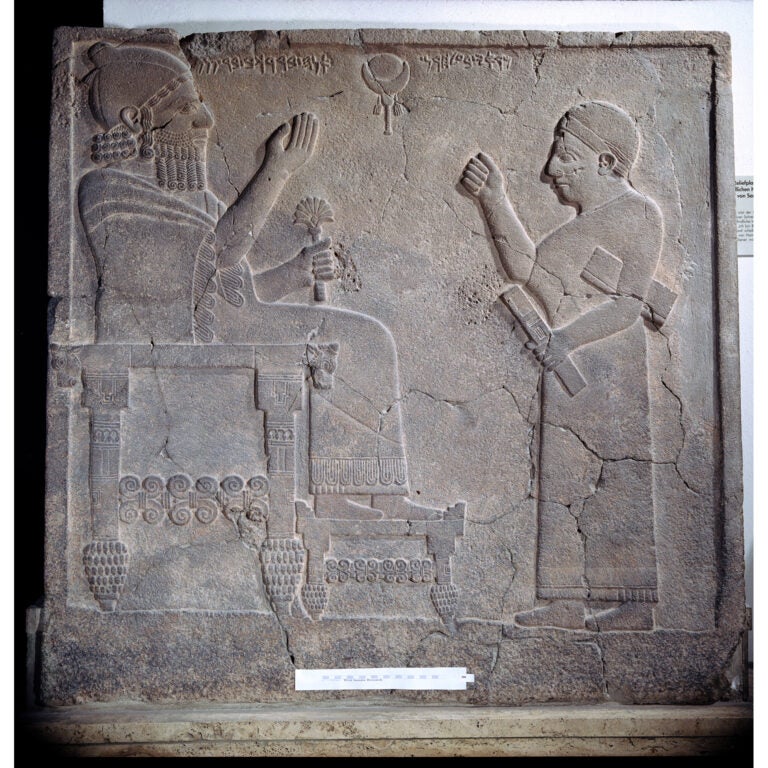

The Semitic language of the Aramean inscriptions, as with their other cultural traditions displays a blend of Syrian, Anatolian and Phoenician elements. The Hittite influence was particularly evident in traditions of royal administration, monumental sculpture and literature. The gods seem to have remained Semitic, at least in name, though Hittite counterparts were often recognized for Semitic deities. Several of the early Aramean inscriptions are reminiscent of Hittite courtly literature known from the Late Bronze Age.

The Hittites had two writing systems: a form of Akkadian Cuneiform adapted for their Indo-European Hittite, and an indigenous hieroglyphic system called Luwian. The Arameans borrowed much from the Neo-Hittites especially in terms of royal and administrative practice. But their Canaanite/ Phoenician alphabet they borrowed from a near-by Semitic culture. Some of the earliest Aramean monumental inscriptions, such as those from Sam’al are written in Phoenician with many Aramaic elements. Although they use the Phoenician alphabet instead of Luwian Hieroglyphics their habit of sculpting the letters in bas relief so that they stand out from the stone, imitates the Luwian inscriptions. Most other Aramean inscriptions of the period are scratched directly into the stone.

The Inscriptions

A number of interrelated inscriptions have survived from the Aramean kingdom of Sam’al, modern Zinjirli. These inscriptions enable us to trace the general outline of its dynastic history, as well as the development of its hybrid Phoenician / Aramaic dialect called Sam’alian.

The literary structure of the Sam’alian monumental inscriptions follows older Syrian and Anatolian traditions. The elements of the form, whether memorial or dedicatory, are dictated by the usual preoccupations of ancient princes and generally bear some of the following features.

1. The first priority is to assert their legitimacy of the claim to the throne, of which heredity is the usual basis. They may also want to emphasize their worthiness occupying the throne vis-a-vis their predecessors. This often involves not merely being on par with ancestors but quite surpassing them in any of their featured achievements. It is also crucial to be specially favored by the gods, all the more in cases where dynastic lineage is questionable.

2. Two important tests of their royal quality will be to secure the safety and order of the kingdom. First, they need to vanquish foreign enemies all around. Then, pacify or dispatch rival claimants and other internal enemies to the throne.

3. Then follows a description of the golden days of their rule, their own greatness and wealth as well as the well being of their subjects. They may claim to have established measures of social justice, economic prosperity or other benefits to the subjects. It may have been propaganda, but could have ramifications for the very real threat of rival claimants. In such patrimonial systems the subjects, whether well fed or disgruntled could influence the outcome of palace conspiracies and succession disputes.

4. Another type of achievement often mentioned is the occasion for the inscription itself, namely building projects. Fortifications, gates, temples and palaces all facilitate a primitive sort of temple-palace bureaucracy by which these Iron Age kings governed.

5. The inscription will generally conclude with stern instructions for the preservation of the inscription itself or some aspect of the king’s life and the accomplishments the inscription symbolizes. It may instruct the reader on the proper feeding of the king in the afterlife, as with Panamu I. Or it may specify how successors are to uphold his policy after him and thereby preserve the prosperity it achieved for the subjects. One fascinating dimension of the Samalian royal inscriptions is the way several of the same formulaic elements remain in place while the language, rhetoric and historical circumstances change.

Article Categories

Non-Biblical Ancient Texts Relating to the Biblical World: Non-biblical inscriptions and documents from ancient times that improve our understanding of the world of the Bible.

Biblical Manuscripts: Images and commentary on ancient and medieval copies of the Bible.

Dead Sea Scrolls: Images and commentary on selected Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts.

USC Archaeology Research Center: Images of artifacts from the teaching collection of the University of Southern California.