Introduction

Beginning in June of 2006, students enrolled in courses with WSR founder Bruce Zuckerman at USC and Wayne Pitard at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) were involved in making hi-tech images of ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals and then having the unusual privilege (for undergrads) of conducting original publishable research on them.

While the seals themselves are normally housed in the William R. and Clarice V. Spurlock Museum collection in Urbana, the best set-up to photograph them happened to be located at USC, so UIUC students followed the seals out to Los Angeles to join USC students in learning how to conduct the highly specialized photography. The students used the images in their personal research projects in Fall, 2006 and Spring, 2007. Zuckerman says, “This is the most complex research and teaching experiment I’ve ever tried to do.”

Description

Cylinder seals were an ancient form of “impression seals,” which are used to make a unique identifying mark on some soft surface–much like some modern letter writers who create a personalized metal stamp seal with their initial(s) to stamp into hot sealing wax dripped on an envelope for creative effect. The ancient seals contained carved images and sometimes words that would leave a mirror impression when rolled onto a soft surface, usually wet clay. Due to their cylindrical shape, the image on the seal could be rolled infinitely, repeated again and again if desired.

Thus cylinder seals have two components: the cylindrically-shaped seal itself and the impression it leaves on some other material. Archeologists sometimes find the seal itself, sometimes just its ancient impression.

Impressions have been found most commonly on clay tablets (ancient documents) and their clay “envelopes,” bricks, ceramics such as storage jars (clay pots), doors, and bales of commodities for sale.

The seals were used to “sign” clay tablet documents–in the case of the Spurlock seals, commercial receipts–with the unique seal of an individual such as the seller. They can be compared to a notarized signature today. The impression gave visual proof of the genuineness of the object. They could also be used on the clay “envelope” containing the receipt or letter to prove no one had tried to open it since it had left the merchant’s hand.

Stamped onto a person’s possessions, a seal impression could identify ownership of the object. They were also used in business to protect closed containers from tampering or theft or to seal storerooms full of grain to show if the room had been broken into or not.

But ancient cylinder seals had far more uses than just as signatures or tamper-proof seals. They also stood for the owner and thus had a secondary use as amulets to protect the wearer from harm or use in medical and magical rituals. Often, they had a decorative function when stamped on clay pots, etc. If made of semi-precious stone, they could also have value as jewelry to be worn and were often included in a person’s valuables at a burial. Rulers also used them to give their kingly authority to written decrees, and pass their authority on to underlings to do business in their name.

Cylinder seals are normally small (2-10 centimeters) and shaped like a rolling pin: long, round and flat on each end. They are usually pierced through the middle so they can be worn on a string or a pin. The design on them may be thought of as a photographic “negative”: it is engraved or carved in the harder cylinder material in intaglio, the reverse of the final impression.

Seals were normally made of some hard substance such as stone, rock crystal, glass, or Egyptian faience. And common stones such as hematite, obsidian, steatite were used in addition to semiprecious stones such as amethyst, carnelian and especially lapis lazuli. (Remember, they were also worn as jewelry!) Sometimes even metal (magnetite) or hard clay or softer materials that are less durable, such as wood, bone, or ivory, were used.

Themes of the Seals

It is the themes depicted on the seals that are what interest archeologists most, however. Compared to the prosaic business receipts we are used to today, the designs on cylinder seals were anything but boring. They were often artistic and imaginative and provide us with a vital window into many aspects of the cultures of the seal makers: their religious beliefs, daily life, warfare, etc. The images on the seals often depict:

- religious themes: myths, gods, giants, angelic and demonic beings, mythical beasts, temples, sacrifices, etc.

- battles and hunt scenes: heroes, warriors, captive prisoners

- elements from nature: animals (snakes, boars, lions, hunting dogs, fish, scorpions), grape arbors, the sun, moon, and stars

- grain storage/granaries

- geometric designs

- inscriptions in cuneiform script

Age of the Seals

So, how old are cylinder seals? Well, the ones in the Spurlock Museum collection date from 3000 BCE to the Persian Period (550-336 BCE). However, the first seals, called “Uruk seals,” appeared around 3500 BCE during the Uruk (Biblical Erech) period (4000 to 3100 BCE) in Mesopotamia, a period which predates the Sumerian civilization. The designs on these early seals consisted only of images. Writing (cuneiform script) appears only towards the end of this period and was used to write the non-Semitic, non-Indo-European Sumerian language, usually on tablets of wet clay. From about 2500 BCE on, it was adapted to write the non-related Semitic Akkadian language.

The use of cylinder seals lasted nearly 3000 years, with the latest examples coming from about 400 BCE (the era of Socrates and the Ancient Greek philosophers), when the use of cuneiform and clay tablets was dying out. With the passing of clay tablets went the seals used to “sign” them, and Near Eastern civilization then went back to stamp seals, better suited for paper and newer writing materials.

Photographic Innovation at WSR

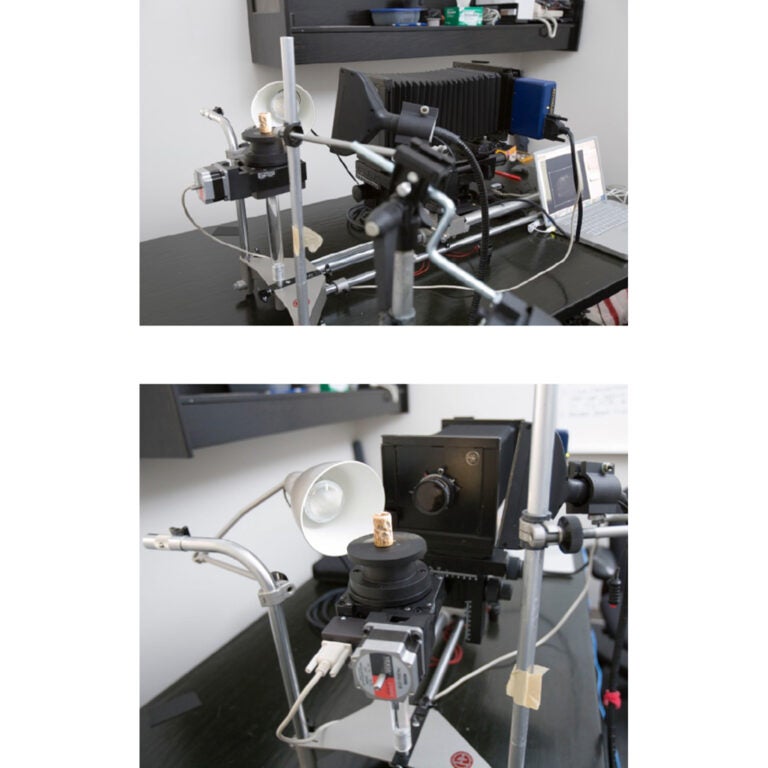

THE SEALS: Unlike clay tablets, cylinder seals are challenging to photograph successfully because of (a) their relatively small size and (b) their 3D design, making it hard to capture the full image at one time. However, West Semitic Research in collaboration with industrial designer John Melzian and Matt Gainer, USC’s digital imaging director, has devised a cutting-edge photographic technique to create one flat “roll-out” image of all sides of the seal itself as it slowly revolves on a platform. Thus, in the final image, the seal’s complete design can be seen from all angles at once.

THE IMPRESSIONS: In the past, the best that could be done was to sketch or photograph a flat, modern impression made by the ancient seal; however, showing the impression from only one lighting angle could seriously bias how the viewer saw the image. Hand drawings were sometimes made, but with a subjectivity problem: the artist drew what s/he subjectively saw. With the aid of Tom Malzbender, a Lab Scientist in the Media and Mobile Systems Lab at Hewlett-Packard Imaging Laboratories, W.S.R. has been employing a new technique for creating as objective an image of a seal impression as possible, a PTM file (polynomial texture mapping). In a PTM image, the end user can view the same object from many different lighting angles. It’s as if the user had the original object before her or him and could shine a light at a surface from any angle s/he chose.

Photographs by West Semitic Research and the Spurlock Museum. Courtesy Spurlock Museum.

Student Research on the Spurlock Seals

“Behold, there came wise men from the east . . .” (Matthew 2:1)

For their final projects, the USC and UIUC students were asked to come up with a Powerpoint presentation of their research on one cylinder seal, describing the object itself (dimensions, weight, material it’s made of, geographic origin, etc.) and giving their own (informed) interpretation of the visual elements on the seal and their original meaning.

One striking example presents three figures that have been identified as three Persian magi (singular magus), or court priest-astronomers (the same kind of officials as the Wise Men of the Christmas story). This is how cylinder seal expert Edith Porada describes the three figures on this seal: “A Magus [right] before an enthroned Magus [center] behind whom stands an attending Magus [left].”

According to USC student Omar Ahmed, for whom the seal was his final project, the scene can be fairly reliably dated to the Achaemenid period of Ancient Persia (the empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 500 BCE). The elements in the seal image all correspond to common Achaemenid conventions: the “winged sun disk” below the men, a symbol of human power and royalty among the Persians; the three-branched barsom each man is holding (barsom was a sacred plant used by the priests in the Zoroastrian religion); and their style of dress, including the peculiar cap with hood extending down the back.

Ultimately, the students’ research, much of it original, is to be published on a special website through the Spurlock Museum.

Article Categories

Non-Biblical Ancient Texts Relating to the Biblical World: Non-biblical inscriptions and documents from ancient times that improve our understanding of the world of the Bible.

Biblical Manuscripts: Images and commentary on ancient and medieval copies of the Bible.

Dead Sea Scrolls: Images and commentary on selected Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts.

USC Archaeology Research Center: Images of artifacts from the teaching collection of the University of Southern California.