Introduction

The inscriptions of Bar Rakkib are the last in the line of Sam’alian kings. One of Bar Rakkib’s most intact records, a building inscription, was found in 1891. Unlike the other Samalian inscriptions which are now in Berlin, the building inscription of Bar Rakkib is housed in the Museum of Antiquities in Istanbul. It consists of twenty lines, recounting the construction of the second palace between 732 and 727 B.C.E.

Bar Rakkib II

The two inscriptions pictured here were also discovered in 1891. Bar Rakkib II is an incomplete fragment of nine lines; at the right, a bearded man holds a drinking vessel and a fan. Symbols of deity appear at the top. In the inscription, Bar Rakkib declares his loyalty to Tiglath Pileser, “lord of the four quarters of the earth,” and expresses the favor shown to him by the god Rakkab El.

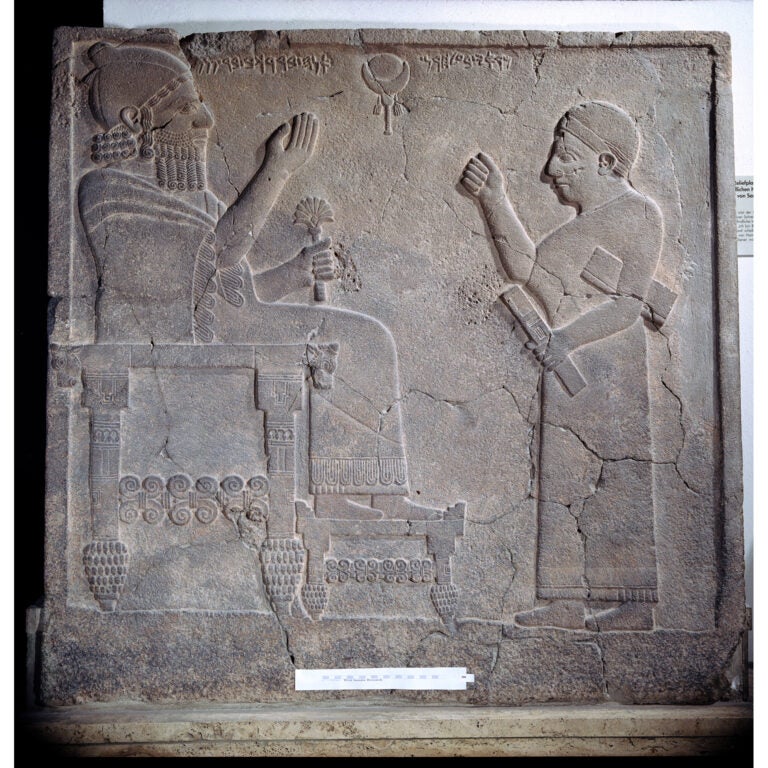

Bar Rakkib III

Bar Rakkib III shows a relief of a king seated on the left, and a servant standing on the right. On the side of the stone is a servant standing with a fan in hand. At the top is an inscription that states, “My lord is Baal Harran. I am Bar Rakkib, son of Panamu.”

Like the previous inscriptions, the letters of the alphabet are carved in Luwian style bas relief. The inscriptions of Bar Rakkib are not written in the Samalian dialect but are some of the first ancient records to use imperial Aramaic. This dialect that by the end of the Neo-Assyrian period had become the lingua franca of the ancient Near East is also found in the Elephantine papyri and in the Aramaic portions of Ezra and Daniel.

As in the memorial to his father, Bar Rakkib emphasizes his own loyalty to Tiglath Pileser III. He refers to a deity unique to Samal, known from Kilamuwa, Rakkab El. The Assyrian king causes him to reign, in fact, on account of his loyalty to his father and to his god Rakkab El. Thus by circumlocution Bar Rakkib credits both the god and his forbears as well as the king of Assyria for his throne.

We know nothing else of any kings of Samal after Bar Rakkib. The Assyrian kings after Tiglath Pileser III began to replace their policy of vassal alliance with annexation and deportation. Eventually, Assyria, and then Babylon and Persia would bring an end to most of the independent, often culturally distinctive Iron Age city states. But it was the Aramaic language that became the lingua franca of these successive empires. With its concise and efficient alphabetic writing system adopted from the Phoenicians, it was the Aramaic language that would bring an end to the cuneiform system used in Mesopotamia since the dawn of civilization.

Photographs by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman and Marilyn Lundberg, West Semitic Research. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—Vorderasiatisches Musem

Article Categories

Non-Biblical Ancient Texts Relating to the Biblical World: Non-biblical inscriptions and documents from ancient times that improve our understanding of the world of the Bible.

Biblical Manuscripts: Images and commentary on ancient and medieval copies of the Bible.

Dead Sea Scrolls: Images and commentary on selected Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts.

USC Archaeology Research Center: Images of artifacts from the teaching collection of the University of Southern California.