Venetian courtesans were fashion trend setters who played artfully with the visual boundaries separating women into distinct groups. They manipulated the visual demarcations that divided women into groups according to the stages of their life cycle and their marital status: that is, maiden, married woman, or widow. They selected clothing from these groups of women in order to create individualized styles. Doing so became easier with the fluid social structure of sixteenth-century Venice where wealth no longer belonged, as it once had in the fourteenth and fifteenth-centuries, to one privileged social register. Their style was individual and fashionable, with unusual color choices and decorative trims, while adhering to conventional sartorial limits.

Costume books like that of the Venetian, Cesare Vecellio, indexes this phenomenon in 1590 and 1598. In his books he provides extensive commentary, often critical, on the dress of his fellow Venetian citizens. He brings to the reader a mine of information about the art, textiles, and world trade systems that made Venice famous. When describing the figure of the “Venetian Noblewomen and Others, at Home and Outdoors in the Winter,” he notes that courtesans, both indoors and outside on the Venetian thoroughfares, match the refinement of Venetian noblewomen but can nonetheless be distinguished from them by their physical demeanor and by the “laws” that restrict their display of luxury goods.

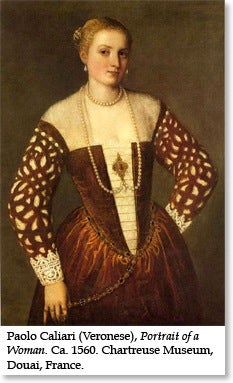

How fast did Venetian women’s fashions change during the sixteenth century and how much did courtesans keep up with these changes? Costume historians locate the most significant shifts in the large transformations in women’s silhouettes that took place approximately every twenty years. These transformations mainly affected the décolleté, the length of the bodice, the shape of the sleeves, and the coiffure. Specifically for Venetian dress the most significant changes can be divided into time periods: by the late 1540s to the late 1550s, the low-neckline bodice is very rigid and opens almost immediately below the breast, stopping at the waist, and often descending below it into a V. The neckline is wide and square and the gown’s skirt is gathered into soft folds. Detachable sleeves are streamlined and edged with richly embroidered cuffs. The coiffure is composed of curls that dangle from the ears onto the forehead.

In the 1550s this silhouette changes when the bodice becomes pointed and extremely rigid, maintained by structural supports known as “costelle” or small pieces of ribbed cotton fabric, that hold the bodice open in the front as the décolleté falls well below the breast and shoulders. This exposed neckline is covered with a “bavaro” – a neck piece, sometimes made of richly embroidered fabric, or a neck ruff in a fan-shape. As the century ends, the ruff becomes increasingly large. The overskirt is tightly gathered and ends in a long train. The coiffure consists of hair pulled to the back which is formed into small “crowns” decorated with gold and silver and fresh flowers. Small curls frame the face or are pulled into nets or head veils.

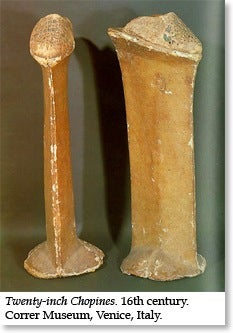

All of these changes extend until the 1590s in the dress of both noblewomen and courtesans In fact, many of the attributes commonly held as the signatures of the courtesan—naked breasts, extremely high platform shoes, pearls, and male breeches—were not universal. Venetian noblewomen of the 1570s also bare their breasts in keeping with the fashion of the day, not just the courtesan. In this sense, clothes were deceptive tools for differentiating Venetian social groups because many Venetians, given the second-hand market, had access to extremely expensive clothes that crossed social and gender lines. Courtesans in particular must have profited greatly from this market as their multiple identities. While costume books attempted over the course of the sixteenth century to classify courtesans’ dress according to specific signs (male breeches, platform shoes, exposed breasts, wearing pearls at their neck despite sumptuary laws prohibiting them from doing so), many women, not just Venetian courtesans, exposed their bodies, towered dangerously above their male companions, and peered from behind silk mesh veils.