Preparing for an online fall semester

By Amber Foster, Ph.D. – April 29, 2020

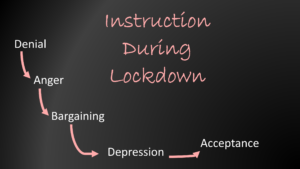

Whenever I look back on this spring semester, I feel like someone who has passed through the five stages of grief. I started with denial (“it’s temporary—we’ll be back in the classroom in a couple of weeks!”), moving through the stages (“maybe if we all wore masks?”) until, finally, arriving at acceptance—realizing that this situation may continue on far longer than we ever believed or hoped it would.

With only days to shift my courses online, spring semester was an exercise in resilience. Although I had experience in online instruction prior to the crisis, moving a course online halfway through a semester was like trying to change a recipe halfway through cooking.

In my denial stage, a little voice in my head wouldn’t be quiet. “If you have to teach this course online in the fall, you’ll need to—” it would begin. It won’t happen, I’d interrupt. I missed my old life, the life where I strolled across campus on my way to class, dodging students on penny boards, nodding greetings to colleagues as they did the same. I missed my bedraggled office, hardly larger than a closet, but whose door opened on a hallway full of students and colleagues and rich intellectual life. I missed walking into a classroom and feeling buoyed up by energy of my students, confident in my ability to read the subtle social cues that told me which questions to ask and when it was time to move on to the next activity—something impossible to replicate in Zoom.

But as the novel coronavirus crisis trudges on, with no vaccine or reliable treatment in sight, we must accept that an online fall semester is on the horizon, and, this time, we can do things differently.

Much of the stress of Spring 2020 came from the need to hit the ground running, jumping over obstacles as they arose. With summer, however, comes the opportunity to recharge our batteries, to slow down and take stock of what we’ve learned. The insight we’ve gained from this ad-hoc spring semester can help us to design courses with the intention of being online, even if they will never be the same as they once were (nor should they be). We can still meet course objectives, and teach students what they need to learn. We can do this because we must—because our collective grief for face-to-face instruction should not come at the cost of human life.

Below are some of my own “notes to self”—things I want to think more about, as I begin to reimagine my courses for a virtual classroom. I hope they help you as well.

Dedicate class time to community building

Students will be missing college life. They won’t be hanging out in residence halls or coffee shops. Greek life will be dramatically changed, if it happens at all. For freshmen, our classes may be their first college experience. Even just five or ten minutes of class time, giving students a chance to talk to each other, can make for a better learning atmosphere—students will be eager to come to class, both to learn and to make friends.

Design participation and attendance policies with online instruction in mind

We all know the struggle: we have students in different time zones; students who keep audio and video off (either because of technical difficulties or because they’re multitasking); students who caught the virus, or who have family members who have caught the virus; students who need to take care of siblings or children during the day; students without quiet work spaces; students who have to share their Internet with the rest of the household—the list goes on. One thing is clear: attendance and participation policies need to be more flexible, but also more clearly articulated. If our departments do not standardize this, our syllabi will need to state our expectations for “participation” and “attendance.” Some questions I’ve been asking myself lately include:

- For synchronous learning, do we want to enforce camera-on participation? If so, would we need to ask students to purchase high-bandwidth Internet at the start of the course, the way we might require a coursebook?

- How can we incentivize active, camera-on participation in the synchronous classroom, without reinforcing class discrepancies (who has good internet/quiet workspaces, and who does not)?

- What do we do about time zone differences? Thus far, recording the session and having the student watch it back has been the improvised solution, but we all know this isn’t good pedagogy in the long term. Those students aren’t actively participating in the course—they go from active to passive learners, especially in seminar-style classes. They may also be fast-forwarding to the relevant information they need to do make up work. For a 16-week semester, should we require that students in other time zones be able to participate synchronously (and only enroll in courses they can “attend”)?

- How can we make attendance policies more flexible? In many departments and programs, there is a “cap” on the maximum number of allowed absences, even in the case of legitimate excuses (such as illness). However, during a pandemic, I suspect we will need to provide more asynchronous ways for students to make up attendance, particularly in the case of virus-related life disruptions or technology fails.

- Should we (or can we) design hybrid courses that could be attended either synchronously or asynchronously? What would that do to our class dynamic?

Think about best practices for asynchronous activities

Recorded lectures and online quizzes may have worked fine for the emergency shift to online instruction, but for a 16-week semester, we can be more innovative with our asynchronous pedagogy. Best practices for online instruction include things like increasing student interaction and emphasizing quality of student work over quantity. I discussed this in greater depth in a previous blog, but the quick recap is to start thinking about asynchronous lesson design within the context of student engagement. Sixteen weeks is a long time to be fully asynchronous, given that attrition rates are generally higher for online courses.

The upshot is that we’re here at USC, a place where we have many resources at our disposal. We have excellent tech support through ITS, and the USC Center for Excellence in Teaching is offering free training in online instruction. Even if we don’t have the technical resources or expertise to design Coursera-level online courses, we can certainly make our current asynchronous teaching practices more effective and engaging.

Design synchronous lessons with “Zoom fatigue” in mind

Synchronous classes are more dynamic, but students with three or more classes per day on Zoom quickly get exhausted (much like we faculty do). As National Geographic writer Julia Sklar writes, Zoom fatigue results from having a “continuous partial attention”—the cognitive exhaustion that comes from excessive multitasking. She notes that “For some people, the prolonged split in attention creates a perplexing sense of being drained while having accomplished nothing. The brain becomes overwhelmed by unfamiliar excess stimuli while being hyper-focused on searching for non-verbal cues that it can’t find.” As instructors, we have to find ways to blend synchronous and asynchronous learning, for the health and well-being of everyone. Even during synchronous teaching, we can mix “camera on” and “camera off” activities, to keep Zoom fatigue to a minimum.

Make the online classroom more accessible

This semester, I had a student with a severe migraine disorder. “It’s worse when I look at a screen,” they told me. I did my best to accommodate the student’s disability with voice-only office hour chats, and by allowing the student to keep their camera off during class time. But I’m concerned about all the students with disabilities who might be struggling due to the shift to online instruction.

For example, deaf or hard-of-hearing students may have been hit especially hard by the crisis. According to Andrea Lust, an RID-certified[1] American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter here at USC, some professors this semester failed to remind students to embed captions in their presentations. Others didn’t share PowerPoints with deaf students in advance, which forced them to choose between watching their interpreter and watching the slideshow. Lust explains that, while it can be awkward to pause after asking a question, it’s a necessary step to give deaf students time to respond. “It’s okay to call on deaf students to offer their opinion in class,” she says, adding, “they are always excited to be included.”

Anticipating potential accommodations can make life easier for everyone, and help us to avoid unintentionally leaving students with disabilities out in the cold. At the same time, after courses begin, we have to talk to our students, and encourage them to tell us what they need to succeed in our courses.

For more on accessible classroom practices, see the office of Disability Services and Programs (DSP)’s guide for faculty.

Consider student mental health

Student mental health is bound to be a major issue in the fall. College is a stressful during the best of times, and existing mental health conditions will likely be exacerbated by protracted periods of social isolation. In our summer preparations, we should make sure we have information about campus mental health and crisis intervention resources close to hand. Our syllabi should emphasize resources available online; we may also want to learn more about how to recognize the signs of a student in crisis in an online learning environment.

Think about privacy

There has been considerable debate about the ethics of recording online class sessions. I don’t have room to go into all the complexities of that here, but in a nutshell, nobody wants their classes, homes, or not-ready-for-primetime selves to suddenly show up on YouTube. I intend to put a disclaimer on my fall syllabus, putting in writing that class recordings are for individual, educational purposes only, and not to be shared elsewhere. In addition, U.C. Berkeley put out a helpful guide with strategies for ameliorating some of the safety and privacy concerns that come with recording Zoom sessions.

—

Final Thoughts

I know I’m not alone when I say I could use a break after this semester. I expect I will need to sleep for about a week once I’ve submitted final grades (I’m also hearing a lot of talk about something called “Tiger King.”). In any case, after a nice, long rest, we can begin thinking about the fall. Our students will appreciate online courses that feel organized and well-structured; at the same time, our teaching experience will be less stressful, as we will have had more time—not to mention the wisdom that comes with hindsight—to develop more innovative online courses. Instead of seeing an online fall semester as a burden, we can choose to move from “denial” to “acceptance”: to see this as an opportunity to expand our pedagogical repertoires and to “teach on,” no matter what bumps may lie in the road ahead.

[1] Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf