‘Star Trek’ at 50: USC Dornsife faculty discuss what it got right and wrong

This month marks 50 years since the iconic space adventure series Star Trek first took viewers to strange new worlds to encounter new life and new civilizations onboard the starship Enterprise. Launching as the world was working feverishly to put humans on the moon, the series drew from the excitement and wonder of America’s young space program and extrapolated a future of near boundless possibilities.

For many, the show was a source of hope for a better, more technologically advanced future, one that was perhaps more peaceful and just, at least for Earth.

A (myopic) glimpse of the future

Gene Bickers, professor of physics and astronomy at USC Dornsife, recalls viewing the show when it first aired in the mid 1960s. As a child, he found its scientific marvels a welcome diversion.

“It was probably my favorite show when I was 7 and 8 years old,” he said. “It increased my interest in science when the only source of up-to-date information for an elementary school student was the newspaper and the nightly news.”

While audiences marveled at the show’s futuristic technology at the time, Bickers in retrospect sees it as falling short of reality.

“I think the growth of computer power and communication technology over the past 50 years has outstripped the pace that is assumed in Star Trek. The blinking lights on the computer consoles in the show look hopelessly outdated, the communicators used by the crew look like flip phones from 20 years ago, and the smart phones of 2016 do many more things than a Star Trek communicator, even though they are dependent on short-range transmission technology like WiFi and 4G networks.”

Khalil Iskarous, assistant professor of linguistics, would seem to agree, particularly with respect to the universal language translater, a device that was featured heavily in the most recent movie in the franchise, “Star Trek Beyond.”

“I would say that it is possible one day to have a universal translator,” he said, noting that linguistics researchers have been looking for common features shared by different languages, especially those that computers can readily process. “Also, researchers who work on machine learning from a computer science perspective have been making enormous progress on language.

“When the two forms of knowledge are joined, in my opinion, the universal translator will not be far behind.”

Aiming for utopia?

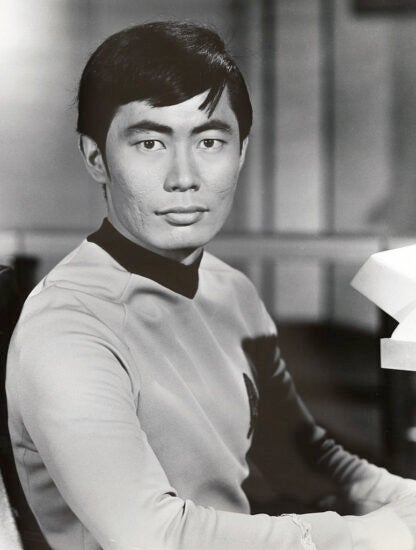

The appeal of Star Trek for many fans may rest in its vision of a more egalitarian society. In the Star Trek universe, people are judged by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin or their gender. For viewers in the 1960s, in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, this message surely must have struck deep chords.

But did the original series really demonstrate a better world? Karen Tongson, associate professor of English and gender studies, suggests that, despite noble intentions, it might have fallen a bit short.

“In many respects, the show used science fiction and its de-familiarized settings as test sites to explore some of the era’s pressing issues, including civil rights, military aggression and imperialism, as well as changing sexual morés and gender roles,” she said. “Star Trek, in other words, explored potential solutions to the issues of its day by giving us a future in which to work it out.”

Still, the show was a product of 1960s America, and despite being set hundreds of years in the future, it had to appeal to the audience of the day.

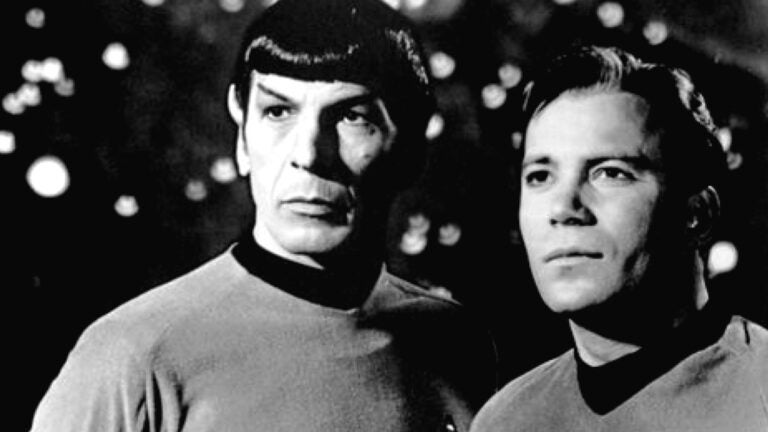

“The show’s drama frequently relied on letting a white, male, virile figure like Captain Kirk run amok and meddle, sometimes aggressively, with other civilizations and worlds,” said Tongson. “This has always been the joke about Star Trek, acknowledged by its legion of fans: Even in its utopian imagining of a future far away from the invasive brutality of what was happening in the mid-to-late 1960s, particularly the Vietnam War, Kirk was still very much a man of the contemporary age — a kind of space cowboy with a tireless libido and a penchant for finding himself involved with people and places with which he had no business.”

Such were the requirements of ’60s performance — and ratings.

Thought-provoking technology

For many, though, the technology of Star Trek was a strong draw. Warp drives, phasers and tricorders made deep space exploration — and weekly adventure — not only possible but exciting.

While faster-than-light travel “remains as much a science fantasy today as in 1966,” Bickers said, those miraculous transporters, capable of disassembling a person in one place and reassembling them almost instantaneously in another, aren’t complete fiction.

“Physicists have used a technique called ‘quantum teleportation’ to transmit the exact quantum state of a single atom from place to place,” he explained, “but this is far removed from the transporter technology in Star Trek, of course.”

Tele-transportation has even sparked serious discussion among philosophers, who contemplate the implications for personal identity of being completely broken down and rebuilt. Would the process mean the death of one individual and the creation of a completely new, albeit identical, person? Or would the original person survive?

Associate Professor of Philosophy Jacob Ross, who has written about personal identity, argues that it doesn’t matter.

“Whether we would survive teleportation depends on how the technology works,” he said. “If it works by moving us instantly from one place to another, then we would survive. If it works by destroying our bodies in one location and creating an exact duplicate somewhere else, then we would not survive.

“However,” he explained, “regardless of how the technology works, if push came to shove, most of us would be willing to undergo teleportation. If there’s a decent chance we’ll be killed by Klingons unless we step onto the teleporter, most of us would do so — even if the technology works by destroying us and creating an exact duplicate somewhere else. What this shows is that what really matters to us is not our own survival. For, from the practical point of view, we’re content with the existence of someone just like us in the future, even if that person isn’t us.”

Despite this realization, it’s interesting to note the reaction of Ross’ colleague Scott Soames, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and director of the School of Philosophy at USC Dornsife.

“I don’t have deep thoughts about Star Trek,” he said, “but you won’t get me in a transporter.”