Longtime chemistry staffer finishes late professor’s decades-long project

Just as it’s harder to have a conversation in a crowded sports arena than in an intimate coffeeshop, random background noise stymies scientists’ best efforts to collect and measure data.

Known as signal-to-noise ratio, it’s important in everything from the quality of recorded sound to the clarity of data generated in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, widely used in modern chemistry to help identify chemical compounds.

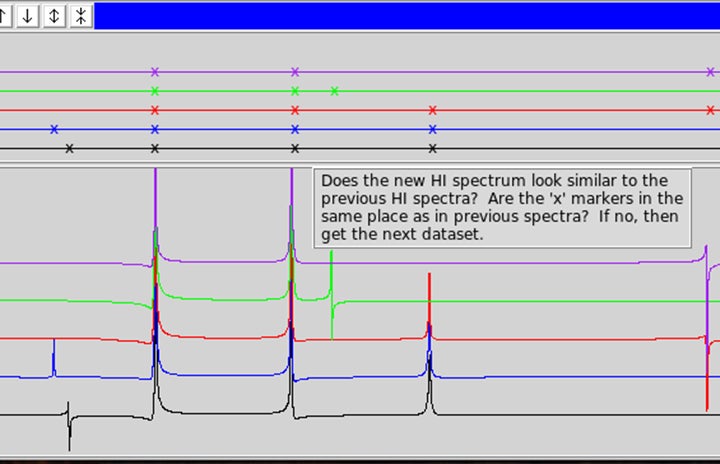

Longtime USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences staff member Allan Kershaw wrote an easy-to-use computer program that rapidly processes data and graphically displays NMR spectra as a series of lines in an image.

The USC Stevens Center for Innovation licensed Kershaw’s software in 2019.

“The software dramatically reduces experiment time and increases sensitivity for one-dimensional NMR experiments,” said Nikolaus Traitler, licensing associate at the USC Stevens Center. This spring, Kershaw received a Technology Commercialization Award from the center for his invention.

Need for speed

The project began more than a decade ago when Kershaw, director of NMR instrumentation in the Department of Chemistry, saw a research group’s need to reduce the time required to collect and analyze data and came up with a computer-based solution to meet it.

At the time, Emeritus Professor of Chemistry and Physics Howard Taylorwas busy developing a mathematical signaling process for NMR data that provided greater sensitivity and resolution at low cost. NMR, which scientists use to observe magnetic fields around the nucleus of an atom, is as central to chemistry as the Richter Scale is to seismology.

A program written by Allan Kershaw improves analysis of the NMR spectrum of chemical compounds.

Taylor wanted to find a better way to separate the valid signals from the surrounding noise, especially when the signal is weak. By comparing different results, they saw that the valid signals would stay in place and the noise would jump around randomly, enabling them to identify which signals were stable and which ones were, well, noise. But there was a wrinkle: The scans needed to be repeated hundreds of times and could take days to generate a large enough sample of usable data sets, Kershaw said.

“Dr. Taylor needed a faster way to process the large amounts of data generated, and I offered to program a graphical interface to do so,” Kershaw recalls.

In the course of a few months, Kershaw created a piece of software that applied Taylor’s mathematics to the NMR data and displayed the results in a format that was easy to interpret.

“My basic contribution was making it usable, taking this very complex mathematical process and putting it into a piece of software so that by pushing a few buttons, you can get the pictures out. We were able to get results out in a fraction — literally one-tenth — the time it would otherwise take,” Kershaw said. “Once you have the data set, you can process it in maybe 15 minutes.”

While he makes it sound easy, the 38-year department veteran admits that he doesn’t fully understand the math underlying Taylor’s research.

Extending a scientist’s legacy

For years, many scientists were skeptical of the value of the mathematical signaling process for NMR analysis that intrigued Taylor, and Kershaw’s invention has helped lead to its wider acceptance.

Taylor, who died in 2015, continued promoting his research interest at conferences until he became seriously ill. “This was Dr. Taylor’s final project,” Kershaw said. “He was really very excited about it working and having it happen.”

Kershaw feels pride in knowing he has added value to important intellectual property being created at USC.

“Over the almost 40 years that I’ve been here, I’ve seen projects go from just an idea in a faculty member’s head to actual applications being sold in the marketplace,” he said. “There’s lots of interesting stuff going on.”