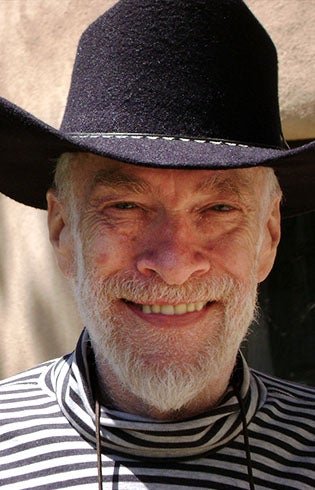

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm explored human conflict and moral origins

In 1983, Christopher Boehm was in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park researching chimpanzee behavior alongside renowned primate expert Jane Goodall.

He’d been advised by Goodall to keep one hand on a tree while watching any of the males. After a few days of uneventful observation of a male chimp named Goblin, however, Boehm decided to ease up on his branch handholding. Almost immediately, Goblin dashed over to Boehm and threw him forcefully into the air. Boehm landed some 10 feet away, shaken but unhurt.

Afterwards, he realized that Goblin must have felt Boehm was ignoring his displays of dominance. Smaller male chimps, Boehm noted, would always cling to trees in the presence of more alpha chimps, while also letting out defiant calls.

These complex interactions became the inspiration for Hierarchy in the Jungle: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior (Harvard University Press, 2001). The groundbreaking book by Boehm, professor of anthropology and biological sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, examines primitive human social systems in contrast with primate communities.

Boehm, who passed away at age 90 on Nov. 23, 2021, was one of just a handful of anthropologists to study primates to better understand human social structures.

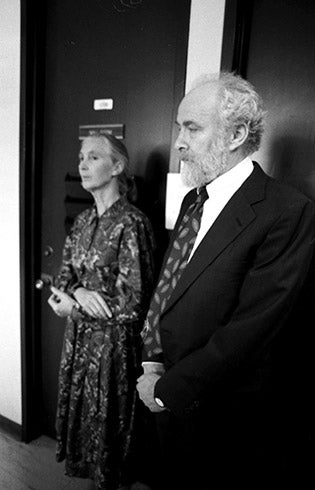

“Chris succeeded in all he did. He was kind, patient and had a great sense of humor. He left an indelible mark on the history of the Gombe chimpanzee research,” says Jane Goodall, who has spent 60 years studying the social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees in Tanzania.

Rain dances and blood feuds

Boehm was born in 1931 to Dwight Boehm and Verna Askey, early Greenwich Village bohemians, and grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His aunt, the painter Alzira Boehm, was married for a time to the painter Waldo Pierce, a close friend of writer Ernest Hemingway. Pierce generously paid for Christopher Boehm’s father to attend Antioch University in Ohio and later for Boehm to attend, as well.

Boehm’s first brush with anthropological observation was in 1951. While hitchhiking in New Mexico on a break from college, he noticed a roadside sign providing directions to a “rain dance.” He asked to be dropped off and then hiked to the site of the ceremony, where Hopi and Navajo gathered in a small plaza.

Boehm watched as a priest and several participants wrapped rattlesnakes around their arms and held the snakes’ heads in their teeth, and saw a teenage boy survive a bite to the face unscathed. Shortly after the end of the ceremony, clouds boiled up and rain began.

The atheist Boehm was deeply, spiritually moved. He described his experience as one of “culture shock,” essential to the experience of being an anthropologist, he believed, and went home to immediately read up on Hopi culture, eventually discovering that the rattlesnakes’ venom was extracted for safety before the ceremony.

After his freshman year at Antioch in 1952, Boehm was drafted into the Army. He was stationed in Germany and while he and his wife, Alice Gibbon, traveled through Europe on their off time, the two became fascinated with a remote tribe of Montenegrins, among whom feuds between clans were often lethal.

The couple vowed to return and study the culture more extensively.

Boehm graduated from Antioch in 1959 and enrolled at Harvard in the social anthropology program. In 1963, he and his wife made good on their vow, returning to Montenegro, with their two young children, to conduct field research for his PhD dissertation.

Alice and the children later left as the second winter approached, but Chris spent a full two years embedded within an isolated tribe at the headwaters of the Moraca River, a nearly five-hour walk to the nearest road.

Boehm’s dissertation deciphering the tribes’ complex management of conflict made him an expert on Montenegrin blood feuds and resulted in a book on the subject, Blood Revenge: The Enactment and Management of Conflict in Montenegro and Other Tribal Societies (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986).

At Harvard in the late ’60s, while completing his dissertation, Boehm had a knack for colliding with counter-cultural movements.

He attended a house party hosted by the LSD researcher Timothy Leary, where a naked Allen Ginsberg dialed up the writer Jack Kerouac on the telephone and Richard Alpert — later known as the guru Ram Dass — worked at the kitchen table. Boehm, the only sober attendee, debated the moral complexities of drug experiments with Leary until the wee hours.

On a separate afternoon, a fellow Harvard student took Boehm to a Boston biker bar, where she introduced him to a friend named Smitty, a member of the Hells Angels motorcycle gang. Intrigued by Boehm’s rugged experience living with the Montenegrins, the biker invited him along for a weekend of camping.

After taking a swig from a communal bottle of wine the first evening of the excursion, Boehm was informed it contained LSD. Undaunted, he continued his winning streak in the group’s poker game.

Boehm continued a loose friendship with Smitty and the gang while he finished his PhD, inviting the local chapter president to present to one of his anthropology classes on the communal lifestyle of the Hells Angels.

“Smitty came over to dinner and we all played ‘cheating poker,’ where everyone tried to cheat without my 9-year-old self catching them at it,” recalls Boehm’s daughter Jenny Morrissey.

Chimps on camera

Following the completion of his PhD in 1972, Boehm began an academic career, first at Northwestern University and then at Northern Kentucky University. While at Northwestern, Boehm’s interest began to shift to primates and how their behavior could provide clues to the formation of our own social structures and morality.

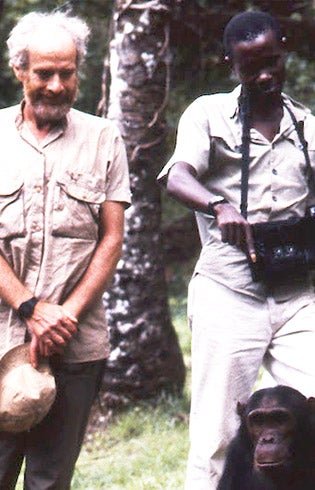

In 1983, Boehm was introduced to Jane Goodall at a fundraising event. Their ensuing friendship and collaborative work lasted many decades, and helped steer Boehm’s research into an entirely new direction. For six years, he summered with Goodall at Gombe National Park, the site of her extensive research into chimpanzees.

Boehm received Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation grants in 1983 and 1987 to study how chimps pacified fights. With this funding, he and Goodall purchased cameras and portable generators to power their equipment. Boehm captured some of the first film footage of chimpanzees, including scenes of male chimps patroling the edges of their territory. He also trained Goodall’s field assistants in how to use the cameras, starting a long tradition of filming at Gombe.

“He made a huge difference to Gombe research by introducing video recording of chimpanzee behavior. He did a lot of video recording himself, despite suffering quite often from back trouble,” says Goodall. “On top of everything else, it was Chris who more or less forced me to use a laptop. Prior to that my most sophisticated way of writing was with a manual typewriter!”

Later, this research would bring him to Washington, D.C., at the behest of former President George W. Bush’s advisor, Andy Marshall, at the start of the Iraq War. Marshall and military officers were intrigued by Boehm’s research into human conflict resolution, as well as his footage of chimpanzees, and felt his insights might be useful to the war cause.

Boehm presented footage to the military men, who noted that the chimpanzees on patrol moved nearly identically to their own human infantry patrols.

Independent scholar

In 1991, Goodall helped establish the Jane Goodall Research Center at USC, which built a database on the social and moral behavior of hunter-gatherers. Goodall helped to bring on Boehm as director of the center, and he remained with USC up until his death, switching to the biological sciences department in 2002.

Craig Stanford, professor of anthropology and biological sciences, remembers Boehm as the quintessential professor figure who sported tweed jackets even on USC’s hot summer days.

Boehm often helped advise Stanford’s students. “Our offices shared a wall, and I could hear him having long conversations with students,” says Stanford. “They would leave his office and always remark on how interesting he was.”

Although he may have looked the part of the serious academic, Boehm had a playful side, as well. After the successful publication of his PhD research as a book, he rewarded himself by never shaving his beard again. A doctor advised him to become a vegetarian for health reasons, advice he strictly followed, but once a month he allowed himself a day of decadent meat-eating.

His colleague G. Alexander “Zandy” Moore, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at USC Dornsife, remembers Boehm as an avid clog dancer who would head to a bar out in the San Fernando Valley on Thursday nights for dancing.

And, when raising his two children, Jenny and Michael, he declared Friday a day when table manners could be ignored — an important experience for children to learn why rules exist, he thought.

In the 1990s, Boehm purchased a Native American-inspired, traditional round house in Santa Fe and commuted to Los Angeles each semester. He was researching and writing into his later years, publishing Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism and Shame (Basic Books) in 2012. In 2015 at age 85, he received a grant from the John Templeton Foundation to continue his work building a database on hunter-gatherers.

He was at work on several book projects, including a pet project on the Old West outlaw Billy the Kid, the night before he passed away in his sleep.

“We should all hope to be as engaged in ideas and scholarship for so many years as Chris was,” said Stanford.