Remember Me

As technology advances and our ways of connecting with one another evolve, so have the ways we memorialize people we’ve lost.

When Willard “Mac” McConnell, an American military veteran, passed away at 91, his daughters honored his wishes to forgo a funeral service and instead celebrate his life online. On the memorial website Never Gone, they shared his life story and posted cherished photographs. Relatives and friends shared their memories and signed the virtual guest book.

And because of the nature of social media, where people broadcast their passing thoughts, sometimes comfort comes directly from the ones we’ve lost. Just days before her death, poet, author and activist Maya Angelou, who had been ailing for some time, posted her final tweet: “Listen to yourself and in that quietude you might hear the voice of God.”

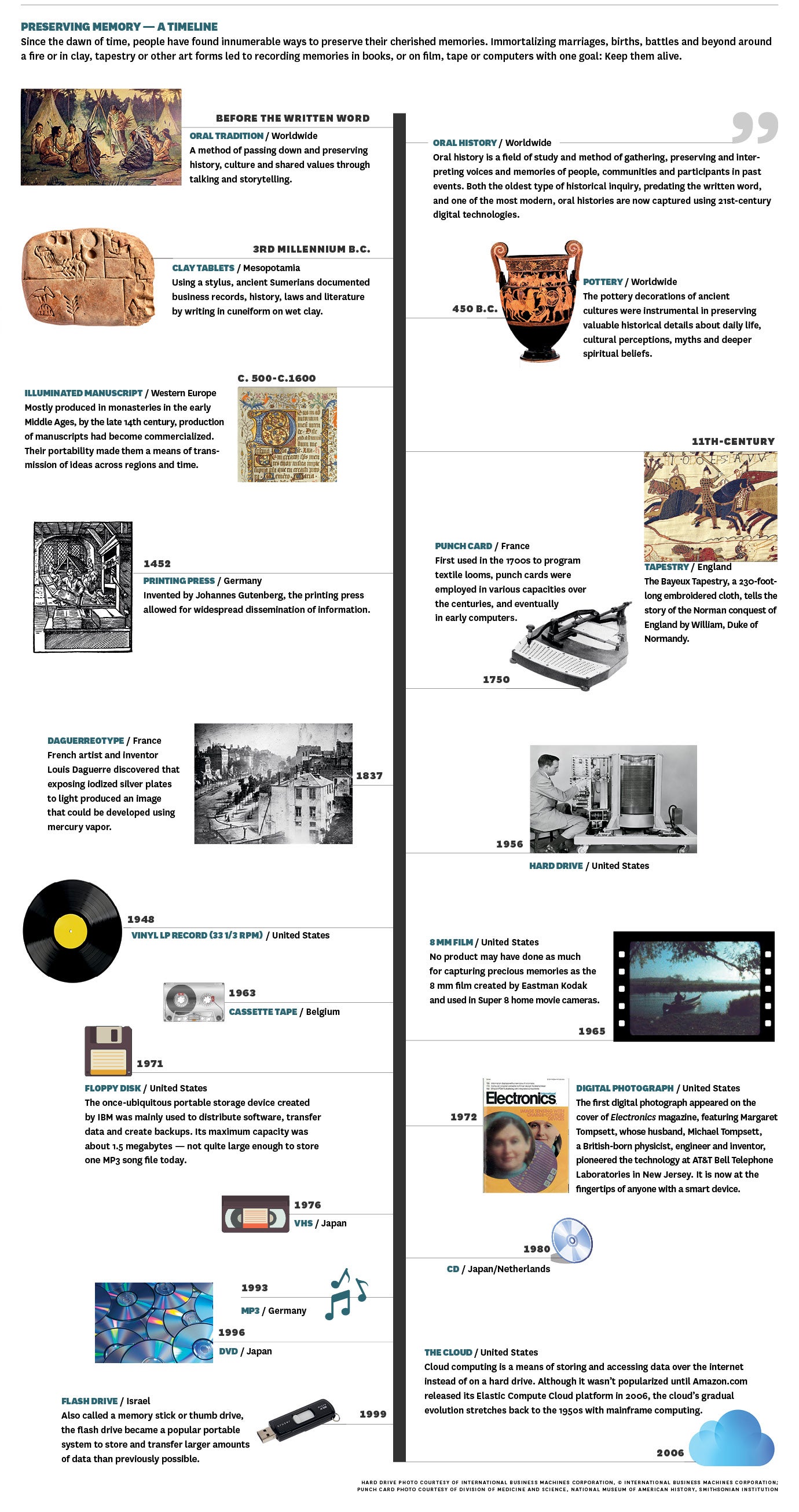

The ways we preserve our memories of the deceased have taken countless forms over time and across cultures. But, the sentiment remains the same: They are always in our thoughts.

Final Notice

Perhaps there’s no greater disruption in our lives than when we lose someone close to us. In that instance, rituals help us find comfort and bring order, explains Diana Blaine, professor (teaching) of gender and sexuality studies, who is an expert on death in American culture.

“Death is a rip in the fabric of a community, and mourning rituals are a way we humans sew the torn pieces back together,” she says. “The creation of memorials is one such ritual behavior — an attempt to produce continuity and provide permanent memories in the face of abject loss.”

The ways we choose to remember and honor people we’ve lost are as personal as the options to memorialize them are countless. And, technology has only augmented the possibilities.

It all starts with a notification — whether it be a phone call, a funeral announcement or an obituary. Legacy.comprovides the last online. The site is one of the largest web presences for online obituaries, publishing features from 1,500 newspapers and 3,500 funeral homes, and reporting more than 40 million unique visitors each month.

Next comes the tribute. We need only browse the web to find countless services to host a memorial website, with names like Forever Missed, GatheringUs and Remembered. And with the current coronavirus pandemic, memorial services themselves have gone online. Many are being livestreamed to uphold physical distancing measures for safety.

Genealogy sites like Ancestry.com and Archives.gov offer ways to trace our family histories online. We can even visit the graves of those who have passed by surfing Findagrave.com.

Make a digital stop at actor and comedian Rodney Dangerfield’s burial site in Los Angeles, and we can read the epitaph on his tombstone: “There goes the neighborhood.”

The Digital You

While epitaphs etched in stone once served as a final memoriam, these days we leave a far wider imprint as we commit to posterity our daily chronicles via social media.

Our Facebook posts, tweets, Instagram selfies and Pinterest boards dedicated to cooking, nature or obscure Italian films leave behind a digital trail of our lives — some carefully curated, others fragments that when pieced together create a mosaic portrait.

In death, social profiles often evolve into memorials where mourners can visit posts on loved ones’ profiles, share their own memories or post messages to the deceased. Facebook even offers a service where members can designate a legacy contact who can turn their page into a memorial after they have passed and maintain it in their honor.

And there are even options for connecting from beyond the grave.

“There are companies that will scour the internet after you die to create a virtual version of you that friends and family can continue to correspond with via email,” says Blaine. Replies are based on a personality algorithm formed from the internet footprint you leave behind.

Add to that holographic avatars — think of Michael Jackson or Tupac Shakur’s posthumous stage performances.

“Such attempts at virtual resurrection are bound to advance and amaze,” Blaine says.

Planned Obsolescence

Although we might think of digital technology as “the future,” like us, it has an expiration date.

Our computers, smartphones and other devices are, for the most part, iterations in a series intended to be upgraded and replaced. Companies discontinue updating older operating systems or supporting software, while for some technology, time is the culprit, degrading the quality of video and cassette tapes, for instance.

But more concerning is that many of us are sitting on stockpiles of precious home videos, digital photographs or audio recordings cataloguing our lives. What happens when the hardware they are stored on is phased out? That thumb drive, compact disc or external hard drive could easily go the way of floppy discs and LaserDiscs.

Since the inception of digital technology, there has been a crisis around preservation, explains Mark Marino, professor (teaching) of writing at USC Dornsife.

“These cutting-edge technologies get left behind by the planned obsolescence that is built into the capitalist version of technological progress,” he says.

Marino is a writer and scholar of digital literature. He directs the Humanities and Critical Code Studies Lab at USC and directs communication for the Electronic Literature Organization, which dedicates much of its work to preserving digital art.

So, how can we save those treasured videos of little ones’ first steps or digitized photographs of great-grandparents? One solution is to archive your content in different formats and keep them in different places, says Marino.

That’s just what USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education at USC Dornsife did with the testimonies it had originally collected on videotape.

In the 1990s, the institute, founded by director Steven Spielberg, dispatched thousands of volunteers around the world to interview survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust and other genocides to preserve their experiences in perpetuity.

But video has a lifespan of just a couple of decades before the quality begins to degrade, and wear and tear was setting in. So, the institute digitized more than 50,000 interviews in multiple formats.

Those testimonies, indexed and catalogued, form the basis of the Visual History Archive, a powerful database that allows scholars and students to learn directly from the people who experienced atrocities. Passing on their stories — to remember them as individuals and empathize with their experiences — advances the institute’s mission to prevent similar events from taking place in the future.

Beyond the Future

As new technologies emerge, undoubtedly the push to memorialize in new ways will emerge right along with them, says Blaine. But, as with all attempts to maintain that impossible connection between the living and the dead, even the most cutting-edge invention will fall short of actually closing the gap, she says. “The most enduring memorial will fade. Just ask Ozymandias.”

The shrine to ancient Egyptian ruler Ramesses II — Ozymandias to the ancient Greeks — may have crumbled, but perhaps ironically his name is still uttered with every reading of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s eponymous poem. Though the monument crumbles, the memory finds a way to live on.

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2020/Winter 2021 issue >>