Pacific Preparedness

Not far from Tokyo’s Imperial Palace, an alarm pierces the air. At a nearby elementary school, hundreds of children drop to the floor, scramble beneath their desks and hold on for dear life. It’s March 9, 2012, two days before the first anniversary of the disastrous 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in which more than 15,000 people died.

Thankfully, this time the “drop, cover and hold” response is just a practice drill — with more than 158,000 participants taking part in the first Japanese ShakeOut.

Developed by the Southern California Earthquake Center (SCEC) housed at USC Dornsife, the 7-year-old ShakeOut program is one of many ways USC is working to keep the Pacific Rim safe, whether from natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis or manmade threats such as cybercrime.

A lot of shaking going on

Last year more than 24 million people, including 9.5 million Californians, participated in Great ShakeOut drills around the globe, rehearsing earthquake survival tactics that can mean the difference between life and death.

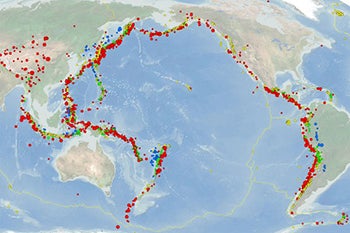

Not surprisingly, many Pacific Rim nations are signing up to participate. After all, this 25,000-mile-long horseshoe-shaped zone isn’t dubbed “The Ring of Fire” for nothing. About 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes occur in this region, which is also home to 452 volcanoes. A nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs and belts and tectonic plate movements make it geologically volatile.

“As a major research university located on the Pacific Rim’s eastern edge, USC is ideally placed to lead efforts to help the region prepare for inevitable disasters,” said SCEC Director Thomas Jordan, University Professor, William M. Keck Foundation Chair in Geological Sciences and professor of earth sciences.

Led by USC, SCEC is a collaboration of more than 60 institutions, including Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Columbia, Stanford and the University of California.

But their measures go beyond drills. They also hunt for seismology’s Holy Grail: more accurate earthquake predictions.

“SCEC is piloting the development of earthquake forecasting, not only in California, but around the world,” Jordan said.

Through the Collaboratory for the Study of Earthquake Predictability, launched by USC in 2006 with support from the W. M. Keck Foundation, geoscientists are using carefully designed experiments to test earthquake forecasting models in different types of fault systems.

Until now, the study of earthquake predictability has been hampered by the lack of an adequate experimental infrastructure. To remedy that, SCEC is working with its international partners to develop a distributed, virtual laboratory capable of supporting global research.

Thomas Jordan heads efforts at the Southern California Earthquake Center aimed at preparing the Pacific Rim for major quakes. Photo by Matt Meindl.

Using software developed at SCEC, more than 400 models are now being tested worldwide, allowing scientists to make detailed comparisons of earthquakes in different fault zones and tectonic environments.

Jordan’s team also is trying to understand aftershocks — why some earthquakes produce swarms of them and some not as many — by comparing aftershock sequences in California, Japan and New Zealand.

“In the wake of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand, where an aftershock wreaked more damage than the original quake, we want to know why different tectonic environments generate differing numbers of aftershocks,” Jordan said.

In the case of earthquakes, information means power. That’s what’s behind SCEC’s partnership with the University of Tokyo’s Earthquake Research Institute and the Disaster Prevention Institute at the University of Kyoto. Through their Virtual Institute for the Study of Earthquake Systems, they look for areas in Japan and the United States at high risk for quake damage.

L.A.’s experiences can offer a lot to Tokyo.

“Like Tokyo, Los Angeles is situated in a vast sedimentary basin, which shakes like a [layered] bowl of jelly during earthquakes,” Jordan said. “When earthquake ruptures occur, they feed energy into those basins, causing destructive ground motion.”

SCEC scientists model these seismic waves and factor them into their hazard calculations, which they are sharing with their Japanese colleagues. This is especially important to public safety in Tokyo and the Kanto Basin, home to nearly a third of Japan’s people.

Said Jordan: “SCEC is unique in its ability to bring people together around the Pacific Rim to focus on how to best predict earthquakes and protect populations against the destruction they cause.”

Flood insurance

Earthquakes are bad enough, but as the 2011 Tohoku quake demonstrated, the tsunamis they can trigger have potential to cause even wider devastation.

Civil engineer Costas Synolakis of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering wasn’t surprised. Synolakis leads a team at USC’s Tsunami Research Center that developed computer models used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association to forecast tsunamis in the Pacific from main warning stations in Alaska, Hawaii and Australia.

“We can expect a tsunami in the Pacific every two years, sometimes once a year,” Synolakis said. “Ten years ago there were no real-time forecasts of where or when a tsunami would strike. Now, thanks to improved forecasting tools developed here at USC, more targeted evacuations are possible.”

USC is the only California university to study tsunamis, he added.

Since 1992, Synolakis has led 20 post-tsunami reconnaissance surveys in the Pacific Rim, visiting Nicaragua, Solomon Islands, Peru, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Tahiti, Japan, Thailand, Samoa, Chile and the Easter Islands.

Their work goes far beyond forecasting: “We visit communities, study what happened and teach locals simple steps to protect themselves.”

Simple lessons save lives. When a 7.3 earthquake hit the South Pacific island of Vanuatu in 1999, residents remembered a 45-minute documentary on tsunamis based largely on USC’s research work and filmed on campus.

“When the earthquake hit, everyone self-evacuated, because after seeing our documentary they knew if they felt the earth shake, they had to run to high ground,” Synolakis said. “So although the tsunami struck at night, wiping out a village that was home to 300 people, all but two residents survived.”

The Pacific Rim is a hotbed of seismic activity.

History repeated itself when a tsunami triggered by the 2010 Chilean earthquake hit Juan Fernandez, also known as Robinson Crusoe Island. Residents knew to self-evacuate, largely after an outreach campaign led by USC a decade earlier.

Synolakis’ goal is to reduce local warning time to less than 10 minutes following a quake and produce location-specific warnings.

“It’s one thing to put the entire Southern California on tsunami alert, and wait and wait and then cancel, and it’s another to broadcast an announcement in ample time, at specific locales saying, ‘A 40-foot tsunami is coming, evacuate now!’ That’s what we’re working toward — targeted warnings with real-time flooding maps.”

Stymying cybercrime

In the months after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami rocked Japan, residents faced another insidious threat: cybercrime. E-mails pummeled inboxes with viruses, and search engines funneled computer users to infected websites. It’s the kind of attack USC’s Terry Benzel would come to expect.

At USC’s DeterLab, Benzel leads efforts to advance new cybersecurity technology.

As the Pacific Rim expands its communications infrastructure, hackers and spammers are looking for vulnerabilities, said Benzel, deputy director of Internet and Networked Systems at the USC Information Sciences Institute (ISI). “The DeterLab can model and analyze new systems and technology to protect against cybercrime and validate new solutions to ensure maximum data protection and Internet security even in the event of natural disasters, like earthquakes.”

It’s especially critical in Japan, where police last year launched a national cybercrime task force — and hacking is such a problem that simply creating a computer virus can land a cybercriminal three years in jail. Cybersecurity is a key area where Japan and the U.S. are deepening their military partnership. In new security guidelines released in April, the U.S. will extend its cyber defense umbrella over Japan, helping its Pacific Rim ally cope with the growing threat of online attacks against military bases and infrastructure such as power grids.

The nation’s cybersecurity chief admitted the nation lags behind the U.S. in combatting the problem, but partnerships like the one with DeterLab could help.

The Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, the Nara Institute of Science and Technology and the University of Tokyo collaborated with the DeterLab to advance cybersecurity in the Pacific Rim. They created and can share a large-scale testbed facility where they can test security.

“We have connected the DeterLab with Japan’s StarBED testbed and run distributed experiments, bringing leading-edge tools and experimental methodologies to researchers in both countries,” Benzel said.

“Our collaborators in Japan are working hard to keep the Internet functioning in the face of natural disasters or cyberattacks. If a tsunami knocks out a large chunk of the Internet, they want to be able to continue to use the net to support rescue operations. Similarly, if a botnet disables key sites, the rest of the Internet should continue to be useful to people.”

Working with USC, Japanese researchers have studied two major problems: how to keep website names correct (DNS security) and how to rapidly re-route connections between browsers and sites when physical connections are failing (Internet routing). DNS security is important as it ensures that you can find websites and services on the Internet and that they can’t be spoofed. All of this work is aimed at creating a resilient Internet.

“To solve them you need to consider how thousands of computers will react when bad things happen,” Benzel said. “Testbeds let us watch thousands of computers at once and make bad things happen to them under careful control.”

Using DeterLab and the StarBED testbeds together “lets us study solutions to these problems in a much bigger world and with more interesting complications than either of us could do alone,” Benzel said. “The Japanese have key insights from their recent physical disasters and USC/ISI has experience creating the large worlds and connecting facilities.

“Together we are able to attack these key problems in ways no one else can.”