One Cool Cat

As a teenager growing up in 1950s Philadelphia, Leo Braudy’s free time revolved around hanging out with friends at the local soda shop, listening to rock ‘n’ roll, watching horror films and thinking about girls.

But, as he shared in his new memoir Trying to Be Cool: Growing Up in the 1950s (Asahina and Wallace, 2013): “The essence of making your mark was being cool.”

The book recounts his early years absorbing and deciphering the world around him, and of course, seeking out that mercurial state of being cool.

“Even more than an awakening interest in sex, trying to be cool opened a new phase,” wrote Braudy, University Professor, Leo S. Bing Chair in English and American Literature and professor of English and history at USC Dornsife.

“One day you were safely within the sphere of family, where your role, like it or not, was clear. The next day you left the realm of blithe boyhood and were trying to construct a personal style in some murky dawn of self-consciousness.”

During the nearly 25 years Braudy took to compose his autobiography, he realized that his adolescent years were monopolized by the attempt to obtain that attitude, that air — that mysterious thing that makes you instantly enviable. In this quest, he cut a rug at synagogue dances. He feigned comprehension during discussions of sex with his pals.

Coolness, he wrote, “could be found everywhere: somebody’s walk, or hat, or way of telling a joke.” The trick was deciding what element of cool you could appropriate and make your own.

Listening to rock ‘n’ roll was a criterion, though Braudy admits he wasn’t immediately overtaken by the genre.

“The appearance of rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t a great flash of revelation to me,” Braudy wrote. “It was more like a pervasive background atmosphere that gradually took over my mind and body, a pulsating web that shaped and timed what I was feeling and doing.”

However, when it hit, it hit him hard. Braudy recalled leaning in, listening to the songs of Joe Turner, Little Richard or Bo Diddley: “When you heard the music, you had to move. Long before there were earphones I sat with my head pressed against the speaker of our Sylvania portable record player, storing the vibrations in my bones.”

Leo Braudy reads from Trying to Be Cool at an event hosted by USC Libraries Dean Catherine Quinlan and the Friends of the USC Libraries. “An Evening with Leo Braudy” took place Dec. 2 at the Doheny Memorial Library. Photo by Erica Christenson.

Writing Trying to Be Cool offered a way for Braudy to parse apart the 1950s through the eyes of his teenage self. The challenge was to maintain his naiveté, he said.

“The book was a way to use myself as a dowsing rod for the culture, to see what was going on as it affected me personally, and as it had a larger penumbra,” Braudy explained at a reading of his new book hosted by USC Libraries Dean Catherine Quinlan and the Friends of the USC Libraries. “An Evening with Leo Braudy” took place Dec. 2 at the Doheny Memorial Library.

One attendee asked Braudy if he thought his book spoke to or against the pervasive perception of the 1950s in America as a touchstone of conservatism and nostalgic ideology.

“This is my individual story,” Braudy said. “But I tried to show the various ways in which that era was not conservative, not single-minded, the ways in which it had a very eclectic view of music.”

Showcasing the inverse of conservatism was, for instance, the Bug, a dance in which participants gather together in a circle on the dance floor. As the music washes over the crowd one dancer gets infected with the Bug, experiencing it as a raucous shake, quiver or some other creative agitation, then passes it on to the next dancer.

For example, at a dance party held at a local synagogue when Braudy was a teen, the second Duane Eddy’s “Night Train” played over the sound system, the crowd went wild, he recalled.

“The Bug was an underground opportunity for even the most inhibited to cut loose with something like community approval and not be embarrassed about it later,” Braudy said.

“In other words, the Bug was the closest you could get to mimicking sex in a public situation. Even when you weren’t being overtly sexual, the Bug implied sex was behind it.”

Dancing was the freest form of expression for Braudy and his friends — whether it was the cha-cha or slow dancing — and those who could do it and do it well were held in the highest regard.

“Of all the things, rock ‘n’ roll music, horror movies, the most memorable thing was dancing — the desire to dance and the feeling that dancing gave you,” he said.

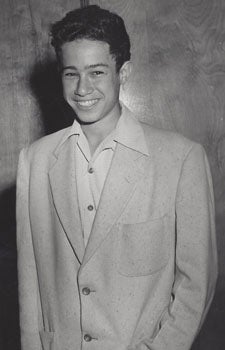

In junior high in 1950s Philadelphia, Leo Braudy (shown here) tried to make sense of the world during the Cold War paranoia. Was rock ‘n’ roll really a Communist plot? Photo courtesy of Leo Braudy.

Braudy is among America’s leading cultural historians and film critics. He teaches Restoration literature and history, American culture after World War II, popular culture and critical theory, including the histories of visual style and film genres. His work has appeared in journals such as American Film, Film Quarterly, Genre, Novel, Partisan Review and Prose Studies.

Trying to Be Cool marks a departure from Braudy’s previous books, which have been scholarly explorations of Los Angeles history, gender studies, and film and narrative theory, among other topics. His preceding publication The Hollywood Sign (Yale University Press, 2011), tells the history of L.A.’s iconic locale marker.

But deny it as he might, Braudy’s cool factor comes through in Trying to Be Cool. After all, he named his chapter titles with song lyrics.

Perhaps Percival Everett said it best.

“The irony of Trying to Be Cool is that the book is so damn cool. It’s Rock Around the Clock for smart people,” noted Everett, Distinguished Professor of English at USC Dornsife. “Leo Braudy captures an American moment.”