Mapping project reveals LA’s Indigenous past, aims to inform the city’s future

The perspective of Indigenous peoples ranks high among the features of a new, historical mapping project of the Los Angeles region, one that offers a resource to guide local planning efforts involving sustainability, habitat restoration and climate change preparation.

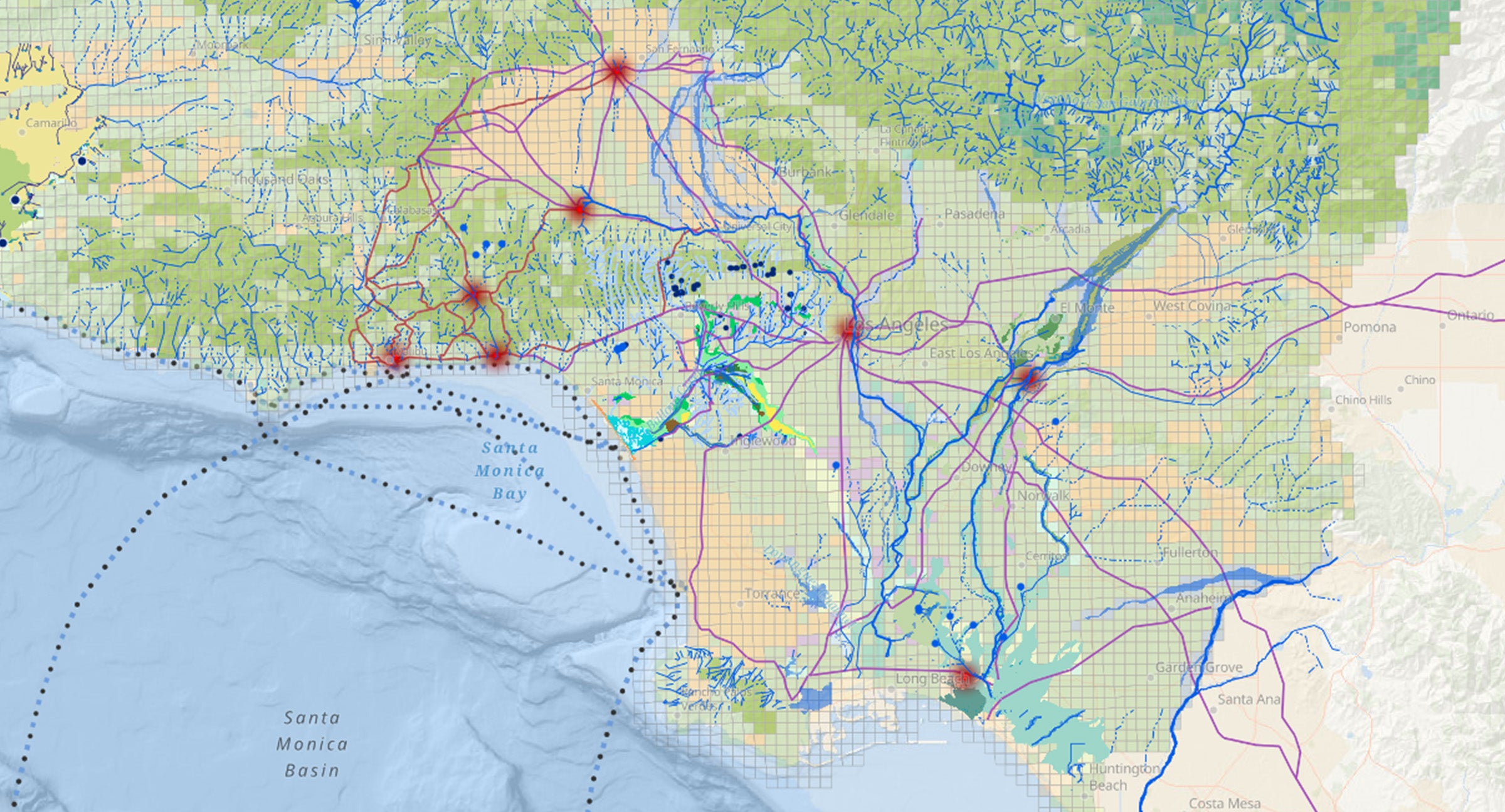

Blending insight from representatives of local Indigenous communities, extensive archival research and contemporary technologies such as spatial analysis and modeling, the long-running project headed by the Spatial Sciences Institute (SSI) at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences has developed the first systematic map of L.A.’s natural ecology.

“Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History” offers a comprehensive view of the region’s natural environment and how Indigenous people interacted with the land and each other in a sustainable way before the arrival of European settlers.

The three-year collaborative effort drew on expertise from USC and four local public universities — UCLA and the Los Angeles, Northridge and Long Beach campuses of Cal State University — as well as three tribes: the Barbareño/Ventureño Chumash, Fernandeño-Tataviam and Gabrieleño-Kizh.

“This work gives rich insights into the ecological and cultural history of Los Angeles along with valuable context that should help city planners, land developers or anyone, including the public, ensure their projects don’t repeat the mistakes of the past,” said John Wilson, founding director of SSI and a project co-principal investigator.

Driving sustainability and deepening connections to place

“Mapping Los Angeles” contributors recognize a more comprehensive understanding of the region’s past can play a powerful role in shaping its future.

Over millions of years, the region’s ecology evolved to resist regular droughts, fires and floods. But as the region became highly urbanized, it exceeded nature’s limits and subjected the area to various inconveniences and dangers. Non-native plants entered the ground. Wetlands were drained and surfaces regraded and paved.

The report delivers important context and framework, says Philip Ethington, professor of history, political science and spatial sciences at USC Dornsife and the project’s principal investigator. It provides residents, leaders and policymakers alike an understanding of how the natural regional ecology operates, which can inform thoughtful and climate-sensitive restoration and sustainability efforts.

“Only with an informed understanding of how this environment operates, and how the indigenous managed it successfully for thousands of years, can we hope to recover its balance and sustainability,” Ethington says.

Beyond the sustainability angle, the project also aims to generate a deeper appreciation of place among the area’s contemporary residents, including how Indigenous people interacted with the land and the region’s pre-urbanization landscape. Tribal scholar Matthew Vestuto, chair of the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians and a co-principal investigator of the report, says the project offers a longer look at what was and, hopefully, inspires what can be.

“I hope our collaborative work ignites a more intimate understanding of place and that people feel more connected to this land we belong to,” Vestuto says. “That way, they love it, take care of it and feel responsible for its health.”

A multi-layered effort to understand the region’s past

Funded by the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation, the 120-page report describes six village sites —modern-day Malibu, Encino, downtown Los Angeles, Whittier Narrows, San Fernando and Long Beach — and provides detailed maps of the natural environment.

Leaning into the work of biologists, geographers and historians, including those representing Indigenous tribes, the project includes:

- Topographic reconstruction: Using sophisticated image recognition tools and an international volunteer effort, the team extracted the elevations of some 15 million individual points located on historical topographic maps to create the first-ever historical digital elevation model of the L.A. Basin from Ventura County to Orange County.

- An aerial photograph mosaic: The researchers linked together various images from 1928 into a continuous map covering 1,745 square miles across the region.

- “Blue line” streams and water bodies: Informed by 1890s and 1920s-era topographic maps from the U.S. Geological Survey, the project team digitized rivers, lakes, streams, wetlands, ponds and other water features. The information can be laid over contemporary maps to reveal the location of buried streams, wetlands and water features.

- Indigenous trade networks and travel pathways: Drawing on extensive archival sources, sketches, Indigenous place names and other records, the project’s contributors constructed a map of the pre-European trade and movement networks across the region. One notable finding: Ventura Boulevard and the 101 freeway corridor was a well-traveled path long before Europeans arrived, asphalt covered the ground and automobiles chugged down the roadway.

- Historical bird distributions: Using nest location records and a natural vegetation map, the project team estimated historical bird species composition, noting how the presence of different bird species shifted with urbanization.

- Plant habitat models: Leveraging both current and historical environmental data, researchers used artificial intelligence methods to develop plant habitat models that suggest historical distribution of notable species, including oak and walnut trees and elderberry bushes.

Combining diverse archival research and traditional knowledge of the area from Indigenous people with modern computational tools that support spatial analysis, mapping and modeling, “Mapping Los Angeles” creates a detailed and multidimensional picture of the landscape as it existed centuries ago.

“All knowledge we have produced or shared has in turn informed additional project components, and it remains a continually growing and evolving research enterprise,” says Beau MacDonald, GIS project administrator at SSI and one of the report’s 19 co-principal investigators. John Wilson, founding director of SSI and a project co-principal investigator, said the report is a multifaceted tool that will pay dividends for years to come.