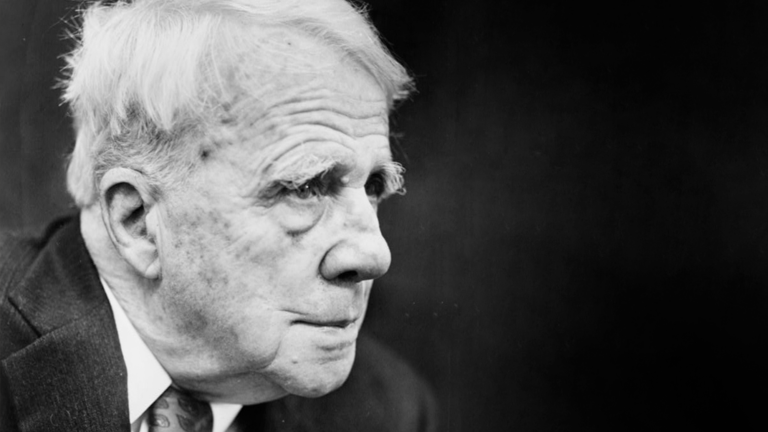

Steeped in tragedy, Robert Frost’s poetry maintains a lasting appeal

At Robert Frost’s 85th birthday party at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel in 1959, critic Lionel Trilling toasted the poet by declaring his work “terrifying.”

This description may surprise most Americans, who nowadays are largely familiar with Frost through folksy fragments of his poems. One hundred years after the publication of his poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” in the collection New Hampshire, which won him the first of four Pulitzer Prizes, shoppers can frequently find the poem’s closing lines — “And miles to go before I sleep” — adorning a variety of mundane merchandise.

The fact that he endures at all is a considerable feat, given that most of his contemporaries are read only in small numbers, if at all. Frost’s public stamina owes much to a masterful simplicity and a rugged pastoralism, which keeps him relevant even in modern times. Tragedy also plays a role, however, say scholars at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“Anyone who has carefully read poems like “Home Burial“ or “Out, Out“ — or almost any other poem by Frost — should recognize the terror in his poetry. And if they did, they would be less inclined to use fragments of his poems or aspects of his life as propaganda,” says Provost Professor of Humanities and Arts Enrique Martínez Celaya, whose art studio includes a photo of Frost with his son Carol Frost, accompanied by a pair of apples from Carol’s orchard.

Disarmingly simple

One factor in Frost’s popularity has certainly been his accessibility. A reader doesn’t require an advanced vocabulary or a profound grasp of world events to make sense of most of his poems.

This has afforded him a broader appeal than, say, Ezra Pound, a Frost contemporary whose poetry is littered with Chinese characters or references to obscure histories. Frost can be read and enjoyed equally no matter a person’s level of education.

It’s an approach that many Americans, who rarely respond well to affected airs, find appealing. “His poems engage with the reader directly, without any sense of hierarchy, reflecting American egalitarian ideals,” says Martínez Celaya.

Frost had one of the most tragic lives of any American poet, and all of this is running through his poetry.

Yet, simplicity doesn’t mean a lack of depth. Subsequent readings of a Frost poem reveal more beneath the initial understanding. The famed lines from his “The Road Not Taken” — “I took the one less traveled by / And that has made all the difference” — are often recited as a cheerful celebration of individuality. Yet, a deeper read of the whole poem reveals that it is, perhaps, a more cautionary contemplation of the ramifications of choice-making.

“Many poems and artworks seem complex and unfamiliar at first, but as we get to know them, they become more graspable and familiar, and they lose their power,” says Martínez Celaya, who has been reading Frost since he was a teen. “In contrast, Frost’s poems appear simple and immediate at the outset but become larger, more haunting and more enigmatic as we spend time with them.”

Robert Frost as poet pastoralist

Frost’s pared-down style was due in part to his adulthood spent on farms in New Hampshire and Vermont. “His simplicity arises from living a restrained life in New England, living with only what you need, primarily dependent on two things: a pencil and an ax,” says Mark Irwin, professor of English at USC Dornsife.

This ruralism also lends to his appeal. It made him relatable to small-town America, a section of the populace often ignored by the literary establishment. His poems are filled with references to the natural world and country life, like his poem on apple-picking, which seem just as relatable now as they were 100 years ago.

Some of this bucolic reputation obscures Frost’s actual history. Frost was born in San Francisco, Calif., grew up in the city and attended Harvard and Dartmouth (although he never graduated). His earliest success didn’t arise in New England but in Europe.

In 1912, approaching the age of 40 with few published poems, Frost sailed with his wife and children to England to try and relaunch his career. The gamble worked, generating connections and publications which that helped him gain attention back home in America, where he returned in 1915.

If Frost wasn’t all homespun farmer, Americans didn’t mind. We have a fondness for those who shape a somewhat mythic personal character, like Theodore Roosevelt posing in buckskin. Frost genuinely did live a mostly rural life where in which he produced masterful work across six decades. At 86, he composed new work and read aloud a poem for the inauguration of John F. Kennedy Jr.

His work ethic seemed to call to mind earlier generations of Americans, says Irwin. “He lived a tough life in the woods, working on his craft. It was a toughness that allows you to survive, the way pilgrims and the homesteaders had to be tough just to survive.”

First as tragedy, then as poetry

This toughness perhaps stemmed partly from Frost’s personal misfortunes, which were plentiful. “Frost had one of the most tragic lives of any American poet, and all of this is running through his poetry,” says Irwin.

Frost’s father died when Frost was a boy. Two of his children died in childhood. His sister and a daughter were committed to mental institutions. His son Carol committed suicide. His wife Elinor first developed breast cancer, then died of heart disease. He’d go on to outlive her by nearly 30 years.

Such knowledge can illuminate a poem like New Hampshire’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” which is often interpreted as a musing on the fleetingness of youth. In light of Frost’s history, it could also depict how the joys of life are inevitably, cruelly, followed by crushing loss.

His simplicity arises from living a restrained life in New England, living with only what you need, primarily dependent on two things: a pencil and an ax.

His probing of tragedy meshes well with America’s own ruminations, in which feats of great accomplishment must be squared with darker legacies of slavery and Westward expansion. The poem Frost read at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy Jr., “The Gift Outright,” which at first glance might read as an approving ode to America’s settler past, has a deeper, tragic edge upon subsequent analysis.

“Many of his poems center on the idea that humans are fundamentally and sometimes irreparably flawed. When they aren’t personally flawed, they suffer from the flaws of others or the unpredictability of an indifferent universe. Still, they often persist in life, even when surrender might appear the logical choice,” says Martínez Celaya.

Frost’s lifelong battle with the “slings and arrows” of fate endures even on his headstone, which reads, “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.”