Knot a Problem

In a USC classroom, Jailyne Olvera, a junior at Augustus Hawkins High School in South Los Angeles studied a knotted rope lying on the table, then stared at a chart of knots.

“Wow, this is hard,” she sighed, her brow almost as knotted as the rope in front of her as she attempted to match the complex knot with one of those shown on the chart.

“Is it this one?” she asked pointing to what looked like a star shown on the chart.

“Remember to count the minimum number of times the rope crosses over within the knot,” prompted USC Dornsife junior Austin Welsh.

Olvera counted carefully. “Six times,” she said, then studied the knot again. Suddenly, her face lit up. “I see it! It’s this one, right?” she exclaimed, pointing to another knot on the chart. Welsh, a mathematics and economics major, nodded. Olvera gave a little shriek of delight and the two exchanged a triumphal high five.

Olvera was playing a game devised by Aaron Lauda, professor of mathematics at USC Dornsife. Lauda uses knot theory to teach students how mathematical knowledge is acquired and processed.

At this May 6 event, he was working with undergraduates enrolled in “Founding Principles of Mathematics and Acquisitions of Mathematical Knowledge,” a new course taught by David Crombecque and devised with Cymra Haskell, both of mathematics. The course, which is meant to engage high school students in modern mathematics, brought 20 students from Augustus Hawkins to the USC University Park campus to participate in a day of math-based games.

The goal of the event: help high school students explore mathematical concepts new to them in an engaging way.

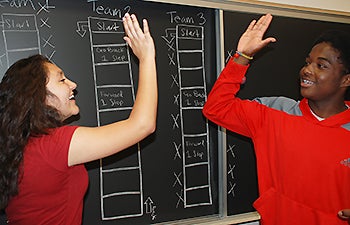

Twenty students from Augustus Hawkins High School in South Los Angeles visit the USC University Park Campus for a day of math-based games. Here, high school students Melanie Alfaro and Eddie Outlaw exchange a high five.

During the semester, the 11 USC undergraduates enrolled in the class visited Augustus Hawkins weekly to mentor the high school students. Each undergraduate helped one or two high school students with math and advised them how to study and prepare for college. The culmination of the course was the game day event, which included a tour of the University Park campus. Funding for the outreach program was provided by Lauda’s National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER Award.

“The NSF CAREER Award is one of the few awards that recognizes simultaneous achievement in both teaching and research,” Lauda said.

Designed to broaden high school students’ perspective towards mathematics, the knot game idea is simple, but has profound implications, Lauda said.

“Imagine taking a piece of rope, tying any complicated knot you can imagine, and then gluing the ends of the rope together so that the knot can never be untied,” Lauda said. “If you and I both perform this exercise, is it possible to tell if the knot you tied is the same as the knot I tied? Our knot matching game introduces the mathematical tools knot theory provides for solving this problem.”

These tools include flattening the knot in order to study how many times within a knot a rope crosses. This provides invariants which can be used to classify knots and draw up knot diagrams.

Along the way, Lauda explained, students were exposed to a new type of deductive reasoning. In order to sort and classify the knots, they had to develop primitive knot theoretic tools.

“We’re trying to teach the high school students that math goes beyond balancing equations in algebra or memorizing multiplication tables,” Lauda said. “There are all sorts of different problems that can be studied using math.”

Crombecque noted that the class lets undergraduates revisit the math they learned from K through 12.

“But they are looking at it through the eyes of college students. They can now think beyond the procedures and understand the deeper mathematical concepts behind what they had learned,” he said. “A big component of the class is to mentor high school students in mathematics during the semester using what they have rediscovered in the class to help the students. For their final project, the task was to come up with games with a mathematical concept.”

Aaron Lauda (right), collaborated with David Crombecque, also of mathematics, to introduce the knot theory game to high school students as part of Crombecque’s new course, which enables USC students to engage high school students in modern mathematics through mentoring and knots. Photo by Susan Bell.

In addition to the knot game — which Lauda devised with the help of Busemann Assistant Professor of Mathematics David Rose — Crombecque’s class of undergraduates created several other games. These included a game based on a popular TV quiz show, a relay race that required students to solve math problems to advance along a track, and a version of battleships using polar coordinates.

“The idea we want to convey is that identifying knots is hard, but by using math you can develop tools to study and analyze such problems,” Lauda said.

“This type of problem doesn’t look like anything students have usually seen before in math. When people tell me they don’t like math, what they’re telling me is that, in a sense, they’ve never really done math. What we see in high school has almost nothing to do with what mathematicians actually do — creating new tools to solve problems.”

Welsh, who is minoring in linguistics, was also surprised to discover an added bonus — an unexpected link with another of his courses.

“I’m taking a sailing class at USC this semester so I’ve done quite a bit of learning about knots in a very different context, with a different goal in mind,” he said. “When I took this class, I really didn’t expect my sailing class and my math class to intersect.”

Nicholas Andrews, a sophomore majoring in economics and mathematics with a minor in computer science, said he had found the communication aspect of the course rewarding.

“It’s wonderful to learn to communicate concepts that I feel I understand really well to someone who doesn’t understand them so well,” he said. “That’s an incredibly valuable skill that I’ve learned.”

Andrews also enjoyed the mentorship aspect of the course in which he’d been paired with tenth grader, Manuel Torres.

“Manny and I both love sport and we’ve bonded over that. I’ve really enjoyed getting to know him. He’s a really smart kid and I want to keep track of him when he leaves high school and goes to college.”

Torres, who has ambitions to study architecture, also appreciated the mentoring program.

“Having a mentor, someone older who I feel comfortable with, is great,” he said.

“Playing these games today made things I’d learned at high school really click in my mind.”