It’s a Barbie world (we’re just living in it)

Like a giant, hot pink sphere of bubble gum, the Barbie movie is rising over the summer horizon. Starring USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences alumna America Ferrera, it’s garnered both fevered enthusiasm and scornful irritation from the public well ahead of its release date.

But why are we all so that worked up about a movie based on a doll that debuted back when Eisenhower was president?

MG Lord, associate professor of English at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, author of Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll (Morrow and Co., 1994), the first book to examine the doll from a feminist angle. She’s uniquely positioned to comment on Barbie: Her book relied on dozens of recorded interviews with those responsible for the doll’s rise to fame, most of whom are now no longer alive.

This research is now the subject of the newly released L.A. Made: The Barbie Tapes, a podcast from LAist Studios. Lord recently sat down to explain how the famous blonde has fused with America’s psyche.

What first inspired you to write a book about Barbie?

I was a columnist for Newsday [in the 1990s], and I wrote this column about cross-dressing my Barbie dolls. At the time I thought it was just massive gender confusion, but in fact it was because my mother had died of breast cancer. I dressed the dolls in that way to protect them, to hide the breasts of the female dolls.

That suggested to me that if these things could lodge in the emotional lives and the heads of kids, then Barbies were bigger than just a symbol of consumerism or corporate capitalism or retrograde ideas about what a woman should look like. They had entered the psyche of children.

Also in the 1990s, the first kids who had grown up with these things were beginning to make visual art and write stories about the doll. It seemed like Barbie was worth investigating.

Barbie debuted in 1959, your book was published in 1995 and here we are in 2023 anticipating a movie about Barbie. Why does she have such staying power?

Some might argue it’s because Barbie is such a hugely recognizable brand. I’d argue that it’s because of the push and pull of the marketplace. Barbie both shapes and reacts to it. There are so many Barbies for different sub-groups now. They recently debuted a Down Syndrome Barbie, and there was a Helen Keller doll with product information in Braille. I love the “Big Tent Barbies.” I think it’s to Mattel’s credit.

Another argument might be that she’s a relatively inexpensive toy. You can get your starter Barbie at a low price. What’s so interesting about Barbie is that she was never the best-selling toy, but she was always solidly number two.

I think there may even be something else at work. She is sort of a mythic archetype. She’s like a Space Age recasting of a Stone Age goddess figure. Even if all of these things are contradictory, it really doesn’t matter because she’s such a wonderful, three-dimensional Rorschach test onto which you can project whatever your beliefs are.

Some say Barbie is sort of sexist, but it seems as if Mattel is trying to reposition her. For instance, you can buy a Barbie that’s president.

Oh, yes, Barbie’s been running for president for years now. She was also an astronaut. I have the commemorative [1965] Barbie Rocket Scientist with her little speech bubble that says, “I really am a rocket scientist.”

Which actually goes nicely with my book Astro Turf [Walker & Company, 2005] and my podcast on the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It’s almost like the Barbie book was about the social construction of femininity in the midcentury and the JPL book, because it deals with my father, who was hypermasculine and working with all those men in their short sleeves with their pocket protectors, is about the social construction of masculinity in the mid-20th century.

Whereas, Barbie is all about women. Barbie is just a girl, at that age when she has really no relationships or responsibility. She has no children. There are no parents.

Can we talk about Barbie’s body? It’s controversial because it’s both idolized and blamed for sparking body image issues.

Barbie was modeled on a German gag gift, the Bild Lilli doll. They’re virtually indistinguishable. The Lilli doll was based on a newspaper comic character who was a sex worker. Ruth Handler took that and projected onto it the All-American girl, which was kind of the message in the 1950s: You had to look like a German sex worker but also be pure and virginal.

Barbie was always positioned as a “fashion doll.” She was in dramatic contrast to the broad-shouldered, Rosie the Riveter woman of the war years. “Dior’s New look” [popularized by fashion designer Christian Dior in 1947] was very hourglass. Her clothes were made up of real cloth, which is why her waist is so cinched in. If you put layers of fabric on a scaled down regular waist, it wouldn’t have the same fashionable lines.

I have a whole chapter in my book where I interviewed a lot of experts on eating disorders. One of the things that stuck with me was how a little girl deals with all the ideals of beauty in our culture and how she is very much influenced by how she is valued by the adults in the home. She interprets the idealized images of women by the way in which, say, her mom and dad react to them.

If a parent makes it very clear that if you don’t look a certain way, you’re a lesser person, then you’re going to get really neurotic about it. But if the parents are casual about it, often those children don’t get eating disorders.

It does seem unlikely that if you simply hand a child a Barbie it’s going to spark an eating disorder.

I’m so with you. It’s like, feminine ideals are the problem and Barbie is the scapegoat.

It looks like Barbie’s eyes have changed over the years.

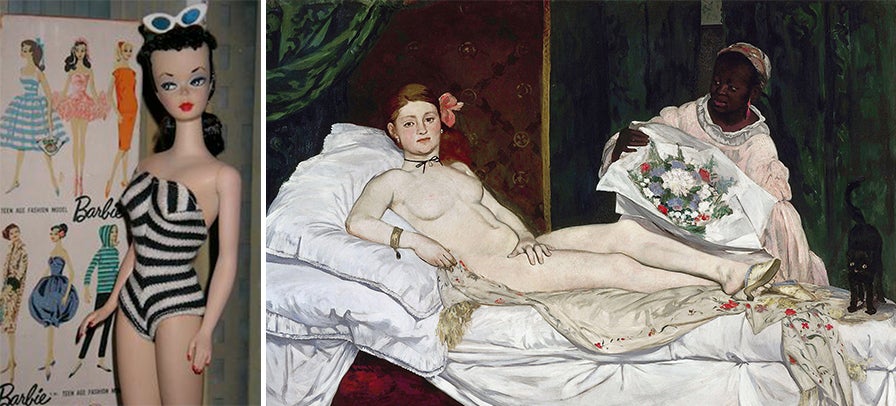

Originally, she had the sidelong glance that you associate with 19th-century pornography. The [1971] Malibu Barbie was the first one that looks straight ahead. I think it was a reflection of the sexual revolution. By 1970, you could have that body, you could be that overtly sexual and actually look at the viewer. It’s like the way that Manet’s Olympia painting was so startling because the unabashedly naked subject was engaged visually with the viewer. It was a defiant meeting of the male gaze with her own eyes.

Barbie’s iconic, arched foot gets a big nod in the film. What are your thoughts on the symbolism there?

Well, you know those ancient Venus goddess figures, they didn’t have feet. They had prongs. You stick them in the earth with the prong feet and they stand up. So, that’s one way of looking at it. A literal way is that they were borrowed from the Lilli doll, which had exaggerated high-heel shoes painted on. That was a big issue with second wave feminists, since she couldn’t stand up on her own.

Why was Ken introduced?

Ken was only made because consumers (mothers and daughters in the late ’50s) wrote in and said she needed a man. In the ’50s and ’60s, a woman without a man, without a husband, was considered a failure. So, they made Ken.

I mean, Ken was an afterthought, an accessory, a slave, a gnat, a fly! You know, the tagline for the movie is “Barbie, she’s everything. He’s just Ken.” In the way that the Mother Earth goddess religions came before Judeo-Christian religion, Barbie came before Ken.