‘Hunger hormone’ turns eating less into eating more

Looking to avoid overeating during those big holiday meals? You might want to avoid fasting in the days beforehand. Cycles of food restriction unleash a “hunger hormone” that increases the capacity to eat more before getting full, according to laboratory research by USC Dornsife scientists.

The insights, published in the journal eLife, could be valuable for helping the researchers develop new weight-loss therapies.

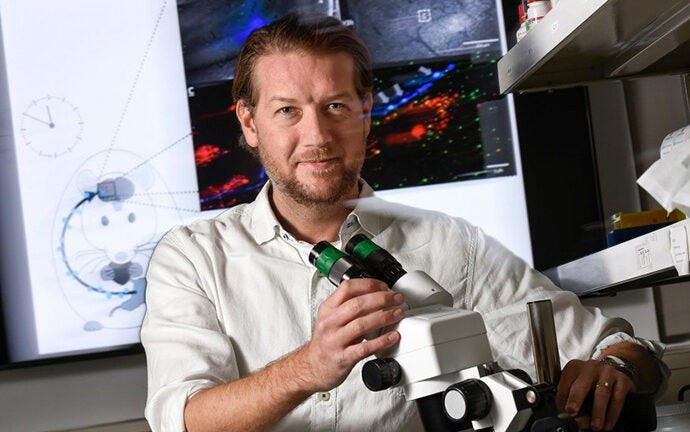

“We are looking deep into the higher-order functions of the brain to unpick not just which hormones are important for controlling our impulses, but also exactly how the signals and connections work,” said lead author Scott Kanoski, assistant professor of biological sciences.

A leftover from feast-or-famine days

Kanoski, doctoral student Ted Hsu and their colleagues conducted their studies in rats, but the work could have implications for humans. The researchers found that when they limited the time rats had access to food every day, the rats gradually were able to double their food intake to compensate.

Over several days, the scientists allowed rats to eat only during a four-hour window, followed by 20 hours without food. The repeated short fasts sparked the hormone ghrelin to go into action prior to anticipated feeding time. That hormone reduced rats’ feeling of fullness when they were eating, so they could eat more.

The hormone’s action makes sense as an adaptive response: To get through times of scarcity, the brain enables the body to take in more calories during times of plenty. But that response isn’t so relevant in the well-fed Western world anymore, Kanoski said. “Instead, we need to find new ways to help us fight some of the feeding responses we have to external cues and circadian patterns.”

The USC team’s study provides a rare look at the way ghrelin communicates with the central nervous system to control how much food is consumed.

Step away from the dinner table

Scientists believe that the hippocampus, a region of the brain that controls memory and motivation, is linked to the way that anticipation of food can increase food intake. In the USC study, researchers found that ghrelin communicates with neurons in the hippocampus to stimulate appetite. These neurons then communicate with another part of the brain, the hypothalamus, to produce the molecule orexin, which further promotes excessive eating. By blocking this pathway in the brain, the researchers reduced how much food the rats ate during the 4-hour feeding time.

In previous research, Kanoski and colleagues found that ghrelin signals the hippocampus to increase rats’ food intake in response to a visual cue the rats learned to associate with an imminent meal. In the human world, that visual cue could be a fast-food billboard or vending machine that triggers a cascade of hunger signals that can be hard to resist.

Ghrelin also has been found to increase the rate at which nutrients pass through the body. When that rate slows down, people feel fuller for longer. Understanding this system as a whole is important for finding ways to thwart it.

The USC scientists are now experimenting with ways to reduce ghrelin’s effects by targeting genes to suppress the activity of the ghrelin receptor in the hippocampus. This in turn disrupts the neurochemical signals that can make it easier for people to overeat.

“More than a third of Americans are obese and another third are overweight,” Kanoski said, “so we feel we have an obligation to help identify new ways to reduce the burden on society and on our health-care system.”