Historian Steve Ross reveals Hitler’s menacing reach into Los Angeles

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, a clandestine war by Japan’s Axis ally, Germany, had already been underway against the U.S. for nearly a decade. The battleground was not some distant shore but Los Angeles, and the soldiers were a malevolent group of Nazis and fascists whose plans included sabotage and assassinating some of Hollywood’s foremost names.

The government widely ignored the growing danger, but one man paid attention. His name was Leon Lewis. He was Jewish, a former executive secretary of the Anti-Defamation League — and among the first Americans to come to terms with the threat that would ultimately slaughter millions and engulf the world in war.

Steve Ross tells the story of Lewis and his fellow patriots in the new book Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017), due out on Oct. 24.

Ross calls his book a cautionary story of “what happens when hate groups move from the margins into the mainstream of American society, and when an American government seems complacent or, as some would argue, complicit.”

By writing it, Ross has fulfilled a childhood vow.

“My parents are both [Holocaust] survivors,” says Ross, professor of history at USC Dornsife. “My father had been in the Warsaw Ghetto and then in Dachau. My mother was in Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, and then a munitions camp in Salzwedel, Germany.” While hearing about their horrific experiences and learning about the Holocaust as a youth, Ross wondered why Jews didn’t do more to stop the Nazis.

Professor of History Steve Ross. Photo by Mike Glier.

Years later, while conducting research for his book Hollywood Left and Right (Oxford University Press, 2011), Ross realized that Jewish inaction against the Nazis before World War II was a false narrative.

Many Jews did try to do something, he says, “but they had a divided strategy. Some felt they should be in Hitler’s face and be very aggressive with an international boycott, while other groups argued that would only force Hitler to double down and persecute Jews even more.”

By 1933, Lewis was tired of the unwillingness of U.S. law enforcement to investigate Nazi activities in L.A. After Nazis held their first open meeting in the city in July of that year, he set about addressing the dangers being ignored by the FBI and Los Angeles police.

Steve Ross’ new book, Hitler in Los Angeles (Bloomsbury Publishing), is due out on Oct. 24.

Starting with four World War I veterans and their wives, Lewis recruited a civilian spy ring. Unlike the swashbuckling spies portrayed on the silver screen, these were men and women from humble backgrounds. But they were even more courageous, because the risks they took were real in infiltrating every Nazi and fascist group in the region.

“Over the next 12 years, [Lewis] discovered plots for sabotage, destruction, mass murder and execution by hanging of famous Hollywood figures and their Christian sympathizers — men like Louis B. Mayer, Al Jolson, Charlie Chaplin and James Cagney,” Ross says.

In the 1930s, however, isolationist sentiments ran high due to the Great Depression’s economic woes and the previous “war to end all wars” still seared into the national consciousness. So even after Lewis’ network began getting results, many still refused to heed the warnings.

“J. Edgar Hoover was so obsessed with tailing Reds that he completely ignored the Nazis and fascists,” Ross says. “And L.A. Police Chief Jim ‘Two Guns’ Davis told Lewis that Hitler was doing the right thing.” Meanwhile, the Justice Department claimed to be hamstrung unless ordered into action by Washington.

This raising of the swastika was part of a 1936 German Day celebration in Los Angeles’ Hindenberg Park, now Crescenta Valley Community Regional Park.

To uncover the actions taken by Lewis and his compatriots, Ross sorted through 200 boxes of their reports. “It took me a while to figure out the story,” he admits, but those documents let him tell much of what happened in the voices of those who were there. “Many of the reports include the actual dialogues of the spies and Nazis involved — including the American Silver Shirt fascists.”

Not all the stories of heroism and courage found by Ross ended happily. Three of Lewis’ spies died under suspicious circumstances, and the book’s final section leads up to what finally forced the entire nation into action — the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

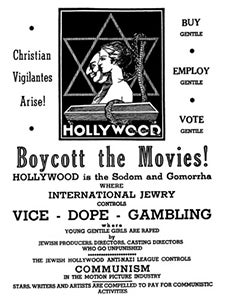

A Nazi call to boycott Hollywood.

After that grim event, FBI agents immediately rounded up nearly 100 Nazis, as well as Italian fascists and Japanese-American agents. Since the bureau had conducted little in the way of investigation before those raids, Ross is convinced the information that triggered them came from Lewis’ network, which had supplied the FBI, Naval Intelligence, and Army Intelligence with the names and information about suspected German, Italian, and Japanese spies and fifth columnists.

“The FBI claimed all of it as their own, but Leon Lewis didn’t care about publicity,” Ross says. “He just wanted the job done.”

In his extensive research to share the tale, Ross realized that the question asked by his childhood self — as well as by fellow historians deep into adulthood — about why Jews didn’t take more action was the wrong one. The real question, according to Ross, is why the American government didn’t do more.

Hitler in Los Angeles is the story of the brave men and women, both Jewish and Gentile, who did more. “They were fighting to protect American democracy and for equality for all,” Ross says.

For this, their only reward was knowing they helped defeat the Nazi scourge. For decades, their story went untold. With his latest book, Ross rectifies this in riveting detail.