New professor rides waves of discovery to decode cellular activity underlying diabetes

It seems fitting that Kate White took up surfing during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Surfing requires split-second adaptation to constantly changing conditions, and its learning curve is said to never truly flatten. The cell biologist, structural biologist, pharmacologist and new faculty member at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Really, the only time that I don’t find myself thinking about science is when I’m in the ocean,” said White, who joins USC Dornsife as Gabilan Assistant Professor of Chemistry this month. “It’s the only way that I actually can relax my mind.” She makes a point of living close enough to the ocean to be able to hear and see it even when she’s not on her board.

White regards the uncertainty of dynamic conditions as one of the most appealing aspects of surfing — and of science. Her research pioneers new experimental and computational tools, including advanced imaging techniques, to reveal the multidimensional structure and function of pancreatic beta cells, which make insulin in the body. Researchers believe that a deeper understanding of pancreatic beta cells and the chemical environment of the cell compartments that store insulin may help cure diabetes.

At the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, White leads the Pancreatic Beta Cell Consortium, a collaborative project that aims to curb the worldwide epidemic of diabetes. This effort is a research cornerstone of the USC Michelson Center’s Bridge Institute, where White was research assistant professor of molecular and computational biology.

Crowd sourcing toward a cure

Kate White. (Photo: Courtesy of Kate White.)

As a tenure-track professor, White will design and build an independent lab and research team while continuing to direct the consortium’s global team of biologists, chemists, computational biologists, engineers and mathematicians who “crowd source” data and ideas.

The group, along with artists and filmmakers, aims to construct a detailed, virtual 3D model of the pancreatic beta cell at both an atomic scale and cellular level.

Collaborators from USC, Caltech, UCLA, the Scripps Research Institute, the University of California, San Francisco, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, among others across the globe use online tools, super computers and data sharing to study diabetes more deeply than could be achieved by individual labs.

“The individual pieces of information that we’re all bringing to the table are useful, but trying to integrate those different data is the ultimate goal, and that’s just impossible for one group to do alone,” White said.

“I’m really excited for my lab to have this outlet to interact with other investigators at other institutions across the world,” she said. “It really adds a clearly distinct collaborative nature to the group that I’ll be growing at USC.”

White’s fondness for T-shirts and office décor celebrating the gamut of science, from Star Trek to DNA cloning, are one of the first things people might notice upon meeting her, said Raymond Stevens, Provost Professor of Biological Sciences, Chemistry, Neurology, Physiology and Biophysics, co-director of the Bridge Institute and co-founder of the consortium.

“Her passion and excitement for all things science position Professor White to be the perfect individual to ‘bridge’ scientific disciplines like chemistry, biology, physics, and also engineering and cinema,” he noted.

Stevens, who hired White as a postdoctoral scholar in 2015, added that those qualities are important for other reasons. “They also open the opportunity for Kate, who is a great communicator, to be able to talk about science to the broader public. USC is lucky to have such a rising star in the exciting new field of whole-cell modeling at atomic resolution.”

The scientist within

White says she’s always loved science and snagged every opportunity to explore the natural world while growing up on a small Illinois farm. One of her childhood friends recently shared an old photo with her from a first-grade book project in which the students declared what they hoped to become when they grew up. Even then, White’s choice was unequivocal — scientist.

Her geologist father and schoolteacher mother fostered her curiosity for nature and getting her hands dirty.

“My parents always allowed me to collect creatures I would find outside,” White recalled. “I would get tadpoles from a ditch and watch them grow into frogs, and then we would release them.”

Her folks even allowed her to build and launch rockets in their backyard. As she got older, White learned how to drive tractors and large equipment on her grandparents’ nearby farm.

When White was in high school, her grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. White immediate dived into reading about the incurable disease to better understand it.

What started as a desire to help her grandmother led to larger questions. “We don’t know very much about human biology; this is strange,” White recalls thinking. “It became kind of this obsession to try and learn about how human beings work, how our biology works.”

Her inquiry also clarified the path of her college studies.

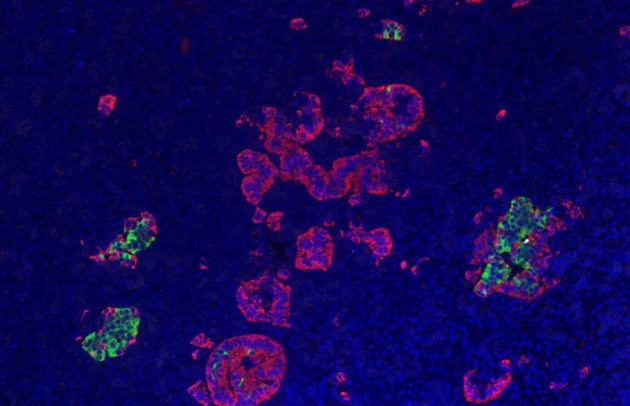

A microphotograph of pancreatic islet cells, including insulin-producing beta cells shown in green. (Image Source: WikiCommons.)

While attending the University of Illinois as an integrative biology major, a search for undergraduate research experience led her to the University of North Carolina, and an intensive summer immersion in a research lab. There, she studied G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are important cellular gatekeepers. These receptor proteins are analogous to messengers that notify cells about incoming environmental changes such as the presence of light, hormones and nutrients. The receptors also can be beneficial as targets for developing new drugs to treat a variety of diseases.

“The trajectory of my career really changed right there,” White said. “I found a home in science because somebody hired me and let me work with them for the summer.” She later returned to the Chapel Hill campus to earn her Ph.D. in pharmacology, investigating how sensitive receptor GPCRs are activated in response to environmental inputs.

Opening doors to build diversity

White feels gratitude for that serendipitous experience. Now it’s her turn to open the door. “I want to give somebody else that opportunity to find their passion and discover what they want to do in science.

She found one important channel for doing just that. “One of the reasons I am excited about joining the chemistry department at USC Dornsife is because I’m part of the Women in Science and Engineering program at USC and want to get even more involved,” she said.

WiSE is dedicated to boosting the representation of women in science and engineering at USC. White plans to recruit undergraduate and high school students for research opportunities and showcase scientists from diverse backgrounds and ethnicities in the classroom.

“As they think about the fields they might belong in one day, students will be able to identify with scientists who have made major strides in those fields,” she said.