Students explore the possibility of extraterrestrial life

On July 30, as millions looked on, the rover Perseverance departed Earth. After seven months traveling through space, it will land on Mars and continue humanity’s search for evidence that life once stirred on the red planet. In 2031, a separate mission will return rock samples gathered by Perseverance back to Earth for scientific study, a first for humanity.

One might wonder why, in the midst of a global pandemic and a climate emergency, earthlings would cheer such an elaborate (and expensive) endeavor away from our own planet, which sorely needs our attention.

Historians can attest, however, that fascination with the universe has captivated humanity for thousands of years, plague or pestilence be damned. Galileo published his seminal text proving that the Earth revolved around the sun in the midst of a bubonic plague outbreak that carried off some 25% of the Italian population. In tumultuous times, an enduring interest in new discovery is an affirmation that life will go on

Vahe Peroomian, associate professor (teaching) of physics and astronomy at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, teaches a class that is testament to this hopeful curiosity.

“‘Astronomy 200: Life in the Universe’ has been around since the spring of 2017 and it fills up every time. When we started, it was limited to 48 seats, and then it went to 90. There’s already a waiting list for the fall class,” he says.

In Peroomian’s class, acknowledging the unknown is welcomed. “We spend the entire course basically finding various creative ways of saying we don’t know,” he explains.

Discovery is a draw for students. “I heard from my friends that the main takeaway of the class is that you cannot be certain if there is other complex life in the universe. It made me want to learn about the circumstances that led to this conclusion,” explains Sean Tay, a business administration major at the USC Marshall School of Business.

Life as we know it

To consider the possibility of life on other planets, one must first understand how life came to be on Earth, says Peroomian. Students start by diving into the birth of the universe and the formation of life on our planet, from the Big Bang to the initial squirming of microorganisms in salty, primordial seas.

Along the way, students discover that Earth’s capacity for life is, well, average. Essential ingredients for life like carbon, water and nitrogen are abundant in the universe. Space is dotted with countless planets, and likely trillions orbit stars at distances similar to that of Earth’s from the sun. The Kepler Telescope, launched in 2009, uncovered some 4,000 of these “exoplanets” circling stars other than our sun

The age of the universe also ensures plenty of time for complex organisms to form. “As soon as life became possible on Earth, it was inhabited,” says Peroomian. “There are planets out there that could have started their evolution of life 7 billion years ago.” In other words, they had as much as a 4-billion-year head start on us.

The cosmos, dark and silent upon initial observation, is thus revealed as humming with potential. Earth suddenly seems a bit less lonely.

“To think that life only arose on Earth because Earth has a special sort of circumstances is the Earth-centered thinking we’ve wanted to get away from for centuries. The only thing that’s special about Earth is that it’s home,” says Peroomian.

Klingons off the starboard bow

After teaching the class a few semesters, Peroomian decided to ask students what they would have liked to learn more about. Their resounding answer? Aliens. So, in the final class, Peroomian takes students through a tour of UFO sightings, alien encounters and deep space signals that may (or may not) prove that intelligent, other-world civilizations exist.

Some, like the infamous Roswell incident, in which a UFO crash was purportedly masked by the government as a weather balloon, seem doubtful, he says. Back in 1947, Russia and the U.S. were at the start of the Cold War. The U.S. was busily testing nuclear weapons and had their eye on Russian developments, as well.

“The army was using very high-altitude balloons to measure radiation in the upper atmosphere of the Earth, and to try to figure out what kind of bombs the Soviets were building,” explains Peroomian. “Apparently, it was one of these balloons that crashed. The reason the government called it just a ‘weather balloon’ was they didn’t want the Russians to know we could monitor their blasts from far away.”

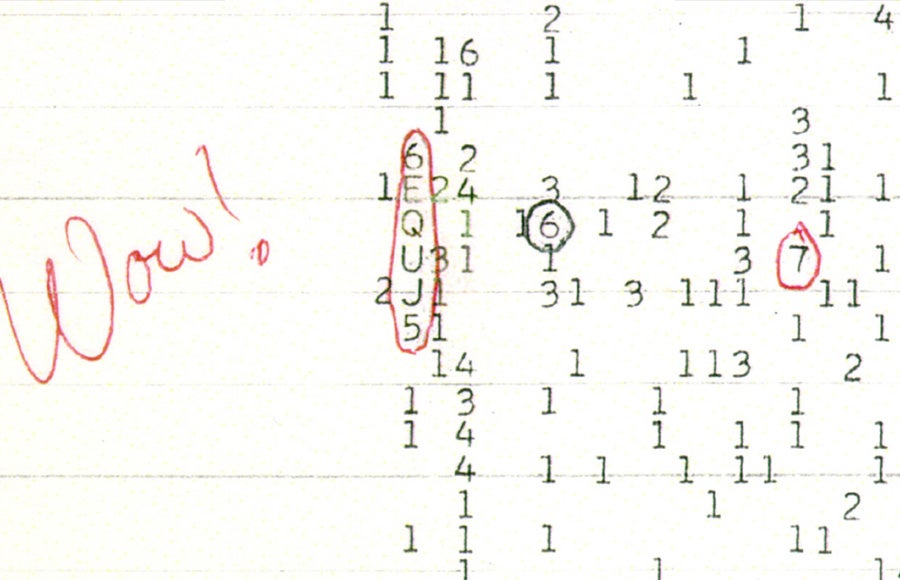

Others, like the narrowband WOW! Signal received in 1977, remain a possible indicator of intelligent life out there, says Peroomian. Picked up by Ohio State University’s Big Ear radio telescope, this unusual one-time transmission from deep space remains unexplained today.

When it comes to the “little green men” of popular culture, Peroomian is skeptical. Bipedal, humanoid aliens indicate that other far flung planets would have had the exact same evolutionary results as Earth. Such depictions of aliens are best chalked up to a dearth of creativity. “Humans can’t imagine things they haven’t seen,” says Peroomian.

Tay agrees. “I am 99% sure that there is life outside of Earth, due to the sheer size of the universe and the number of planets that inhabit it. However, I believe that life out there would be drastically different from Earth’s life and would be beyond our imagination.”

Regardless of the exact physical characteristics of any beings out here, Peroomian feels a continued push to find life in the galaxy should be encouraged. “We want to be part of the galactic civilization,” he argues.

Given the eagerly packed seats in his class, it’s possible that a USC Dornsife student might be the very first to say to an alien being, “We come in peace.”