New center headquartered at USC Dornsife studies COVID-19’s effect on families

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to afflict the U.S., many high-risk businesses such as in-door restaurants and bars, theaters and museums must navigate strict rules of operation. In addition, gyms, churches, hair salons and malls throughout the state face stringent restrictions, and many school districts in the state, including Los Angeles Unified School District, continue to conduct classes online.

The restrictions are certain to ramp up pressure on families, many of whom will be hard-pressed to balance the stresses stemming from COVID-19 with those experienced in everyday life.

The USC Center for the Changing Family (CCF), headquartered at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, recently awarded 14 small grants to fund projects studying how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped family life.

Trouble brewing at Latino-owned coffee shops?

The COVID-19 pandemic is rattling minority-owned small businesses. Karina Santellano, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at USC Dornsife, received a CCF grant to study how Latino-owned coffee shops in Los Angeles are adapting to the stay-at-home orders.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Santellano was researching the intersection of race and class in Latino Coffee shops.

“My original study was going to be an ethnographic study where I interned at a coffee shop,” she says. “COVID-19 began when I was getting into data collection, and it threw a wrench into the engine of the project. So, I began to re-think my dissertation.”

Santellano already had forged a relationship with personnel at the coffee shop where she was interested in interning, which supported her ability to refocus her research agenda.

“I was talking to my contact at a coffee shop who holds the role of social media and marketing manager,” Santellano explained. “He said, ‘My hours are reduced. We are using innovative strategies because we need to sell.’”

Hearing the new decisions these small family businesses face, Santellano shifted gears to interview multiple business owners to see how they are adjusting to the pandemic.

Santellano has currently run 8 interviews and plans to interview 35 business owners total and employees on how COVID-19 has impacted their business strategy, economic well-being and family life.

Santellano’s preliminary findings suggest that coffee shops are going online to maintain sales during the pandemic.

“I have found that they are implementing curbside pick-up, leaning on Instagram, and are still open and taking orders,” she says. “Some [coffee shops] are selling coffee grounds and changing open hours because customer’s daily routines have changed. They are working from home and no longer coming in early before heading to work.”

Santellano interviewed one coffee shop owner in South Gate who was unable to access a small business relief loan early in the pandemic.

“He has a dad who owns a mechanic shop and he owns a coffee shop. He applied for the mechanic shop first, but by the time he applied for himself just shortly after, the website was not taking any more applications,” she says.

Santellano has found that these small businesses are relying on community support during this time given the difficulty of accessing government funds. “They are doubtful that the government will come through for them during these hard times. They are appreciative of community members and family who are stopping by to purchase drinks and other items.”

Santellano plans to document the experience of these workers to shed light on the disparity faced by Latino owned coffee shops and their resilience.

Conceiving a baby during a pandemic

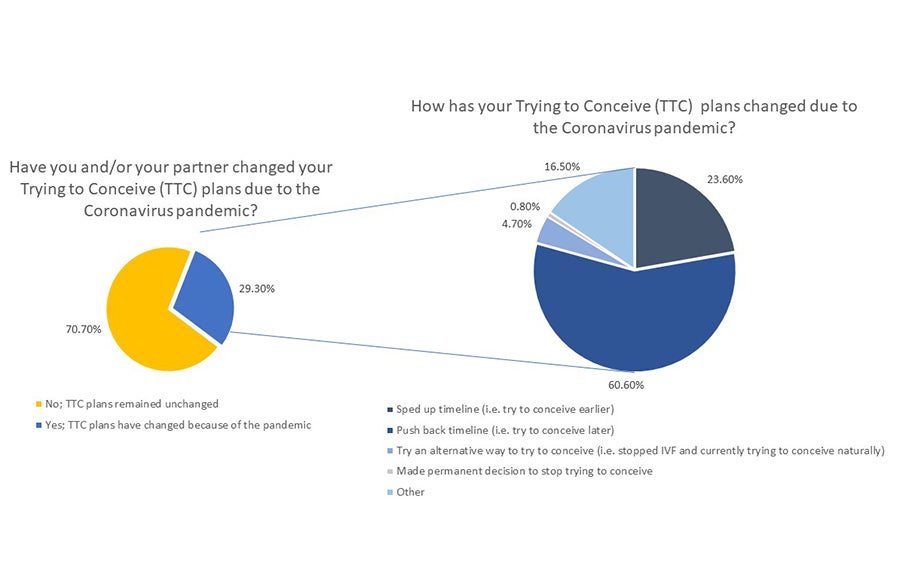

Individuals and couples deciding to start families are faced with new challenges with the COVID-19 pandemic. Christine Naya, a Ph.D. student in preventive medicine at Keck School of Medicine of USC, is using her CCF grant to assess how COVID-19 is influencing people’s decisions around conception.

Specifically, Naya is interested in possible socioeconomic disparities surrounding the pandemic’s impact on people’s family planning.

Research indicates the pandemic has altered plans for many hoping to conceive children. (Image: Courtesy of Christine Naya.)

“There have always been disparities with reproduction. This pandemic is highlighting these disparities,” she says.

Naya is administering online surveys and seeks to capture a diverse population. “I wanted to include LGBTQ folks who may use assisted reproductive technology, sperm banks, egg banks or surrogate mothers. For a lot of these folks, their plans may be altered because many of these agencies are closed,” she says, noting that the American Society for Reproductive Medicine recommended a halt to new assisted reproductive treatment cycles as of March 17.

Naya plans to follow up with her participants in six to 12 months to see how the pandemic ultimately affected their decisions around family planning.

“It will be interesting to see from a health-behavior perspective how large-scale events such as this pandemic affect birth rates. We know that even a small shift in birth rates can have huge cultural impacts, so this is a smaller look at how this shift is happening,” she explained.

Naya is still recruiting participants to her study, and those interested can sign up or get more information on the study site or by emailing ttcduringcovid@gmail.com.

At-risk mothers: intimate partner violence and drug use

Necessary public policies, including sheltering-in-place, restricted travel, social distancing and closure of community foundations, likely increase the risk of domestic violence. Alice Cepeda, associate professor of social work at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, is using her CCF grant to study the impact of stay-at-home orders on young adult Latina mothers in San Antonio, Texas.

Cepeda seeks to understand this population’s long-term risk for intimate partner violence victimization, mental health and drug and alcohol use patterns.

Her project builds upon the 15-year San Antonio Latina Trajectory Outcomes (SALTO) study, which she launched with Avelardo Valdez, professor of social work. SALTO follows a cohort of Mexican American adolescent females with gang-affiliated boyfriends or family members. Cepeda and Valdez found that these teens were highly vulnerable to dating violence, early initiation of drug use and delinquent criminal behavior.

Cepeda interviewed more than 200 women from the original SALTO cohort, many of whom are now mothers.

“The outcomes are not good. These women have chronic intimate partner violence histories. They have been physically and emotionally victimized by partners throughout most of their lives, and some have histories of heroin and meth use,” Cepeda says.

With the help of CCF funds, Cepeda will interview 50 of the mothers. She predicts that COVID-19 will have inflated challenges for her population.

“With the COVID pandemic, these women who have three to four children on average are highly vulnerable for violence victimization,” she says, and this comes with the potential for increased drug and alcohol use patterns, which the women may use to cope with their stress. “Texas has the highest under-insured population in the country, so you add on the additional stress of the pandemic, and we suspect that this population will be disproportionately burdened.”

Cepeda, whose family is from San Antonio, has a personal stake in her research. “I am extremely committed, given I am from these communities. This population has gone unnoticed and are unaware of the health disparities they face.”

Cepeda believes her findings have implications for Mexican Americans and other Latinas beyond just San Antonio. “These women are not immigrants. They are second-, third- and even fourth-generation Americans,” she says. However, according to Cepeda, Mexican Americans, relative to other immigrant groups, have fewer improvements from one generation to the next in terms of finances and well-being.

Shifting to telemental health for child therapy

Telemental health — online or remote therapy — has been underused with young clients. Cassandra Sanchez will develop new guidelines for using telemental health with children from birth to age 5 and their families in her new line of research, supported by a CCF grant. Sanchez, a clinical psychologist by training, is currently a post-doctoral fellow at USC’s University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD).

UCEDD, the mental health program of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, specializes in helping children who have neurodevelopmental delays or disabilities and co-occurring mental health complications. The clinic moved entirely to telemental health in mid-March due to the coronavirus pandemic.

As a clinician, Sanchez has seen firsthand how telemental health can support young children. She plans to survey 100 infant and early childhood mental health clinicians and trainees who actively provide remote therapy to young children. Clinicians will complete an online Qualtrics survey developed by Sanchez that will include quantitative and qualitative information about their use of telemental health with young children their families. She hopes to understand better how families with young children are interacting with telemental health.

Sanchez says that, in addition to allowing for greater creativity during sessions, telemental health also supports patient retention. “There is a lower rate of ‘no show’ clients. There are fewer barriers for a lot of families, whether that is transportation or arranging care for the other siblings,” she explains.

In the future, UCEDD will permanently offer telemental health because of the positive response from families.

Sanchez is optimistic about her project and future findings. “We are at a unique time with this pandemic where many are experimenting with various telemental health interventions. I think capturing the rich perspectives of clinicians trying to apply telemental health will be a huge asset to the field,” says Sanchez.

Life in limbo for immigrant families in detention

Latino immigrant families face an arduous process when a family member is put in removal proceedings, the legal process through which the government determines if an immigrant is to be deported. The COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate the situation.

Blanca Ramirez, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at USC Dornsife, studies the consequences of deportation on Latino immigrant families and the role of legal advocacy in supporting immigrants and their families during removal proceedings.

Before COVID-19, Ramirez interviewed 32 individuals with a family member who had been detained or deported and found they face an uphill battle.

“It takes a lot — emotional strength, financial support — to visit someone in detention, to get an immigration lawyer and to support family members who are at times detained,” she said.

Among most families in her study, a family member was deported, some the same day they were apprehended and others after months in detention.

“That is one part of the punishing nature of immigration law: Families don’t know how long these processes last,” says Ramirez. In light of the pandemic, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has halted family visitation for all its detention facilities, making critically needed family support more difficult for those detained.

Ramirez is using her CCF grant to examine how legal advocates and immigrant families are facing newfound difficulties in supporting individuals during removal proceedings. With COVID-19 restricting movement and commerce, legal processes for detained individuals has become more complicated. Immigration lawyers face more risks and barriers than ever before.

“I talked to an immigration lawyer who detailed how they still have to turn in documents to immigration courts that require signatures. They have to go out to FedEx, and that puts them at risk,” says Ramirez.

Further, some immigration lawyers are required to provide their own personal protective equipment to enter detention centers, many of which are located hours outside of urban centers.

With immigration lawyers facing newfound setbacks related to COVID-19, this adds to the state of limbo for immigrants in removal proceedings. According to Ramirez, some removal proceedings are currently stalled; however, individuals currently detained are still experiencing the same removal process.

“This means that someone who is in detention needs to put in a case while their immigration lawyer might be under stay-at-home orders,” Ramirez explained.

Ramirez’ work provides a platform to consider the new barriers that immigration lawyers and families with detained family members face during the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Research roundtable open to the public

Several researchers supported by CCF grants will present their studies, including four described in this article. The free, online roundtable is open to the public and will take place from noon to 1 p.m. on Sep. 8. More information is available on the USC Dornsife event calendar.

About the USC Center for the Changing Family

Comprising an interdisciplinary group of faculty members from throughout the university, the USC Center for the Changing Family supports and promotes the study of family systems, close relationships, and mental and physical health across the lifespan.