Debunking the myth of legislative gridlock

So much for gridlock.

President Joe Biden’s US$1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief plan is moving steadily through a series of crucial votes in the House and Senate. Its progress toward passage is part of a process known as “reconciliation,” which would allow Democrats to enact the plan without a single GOP vote.

Of course, the massive bill could still be derailed, but Biden has already forged ahead on a flurry of executive orders on climate change, immigration, racial justice and more.

Laws and policy are being made in the nation’s capital, despite its reputation as suffering from partisan gridlock.

The fact is that gridlock has always been a myth, resting on half-truths about the legislative process and a basic misunderstanding of how contemporary policymaking works.

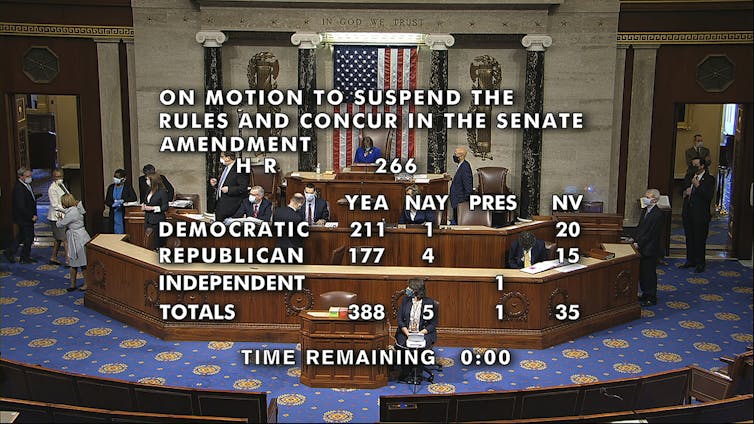

Tally of the vote on approving the almost $500 billion coronavirus package in the House of Representatives at the U.S. Capitol, April 23, 2020. House Television via AP

Legislative obstacle course

Today’s political environment is undoubtedly difficult for lawmakers who want to pass legislation. Party polarization levels are historically high, and slim House and Senate majorities are increasingly common.

The filibuster, which requires 60 votes to pass bills in the Senate, is now routinely used to block legislation. Under these circumstances, Congress crosses fewer items off its “to do” list. Congress’ failure rate on key issues – the percentage of issues that are not addressed on its policy agenda through legislation – has more than doubled from 30% to over 60% since World War II.

Yet there is still significant room to maneuver, and Congress gets more done than you think .

Consider the 115th Congress, which convened after President Donald Trump’s election in 2016, the last time the same political party controlled the House, Senate and Oval Office.

That Congress enacted 442 laws, the most in a decade. A chunk of these laws were mostly symbolic, doing things like designating national days of recognition. But an estimated 306 – 69% – were substantive, according to the Pew Research Center, including a $1.5 trillion tax cut and bipartisan measures on criminal justice reform, farm policy, the opioid crisis and sanctions on Russia.

This places the 115th Congress on par with earlier sessions, which have passed an average of 311 substantive laws since 1989.

Policy is more than legislation

The gridlock narrative focuses too narrowly on Congress and the bills it does or doesn’t pass.

Policy is the set of principles and goals that guide governmental decision-making. Congress may have the sole power to write new laws, but it does not have a monopoly on making policy.

Most obviously, the executive branch can shift policy through executive orders, which averaged 36 per year under President Bush, 35 under President Obama and 55 under President Trump. President Biden is already up to 31 executive orders and counting. The executive branch also uses less visible means to change policy, such as internal guidance memos, circulars, bulletins and other arcane directives.

These policy initiatives fall outside the normal review processes, which require extensive notice and opportunities for public comment. The Trump administration reportedly issued over 1,000 changes to immigration policy using these methods, helping to slash legal immigration to the United States by half.

There are other avenues of policymaking that bypass the legislative process:

• Sometimes officials engage in “policy conversion,” which means repurposing old laws to new ends. In that way, the law stays the same, but the underlying policy sends it in different and sometimes surprising directions. For example, antitrust laws initially targeted business trusts, forbidding organizational practices “in restraint of trade.” Businesses convinced federal judges to apply this general ban to unions, directing the law to new targets. Similar shifts of policy from guarding one set of interests to protecting another can be found in consumer protection law , disability policy and social programs.

• Sometimes Washington makes policy by doing nothing at all. President Biden’s COVID-19 relief package proposes to increase the minimum wage, which has remained at $7.25 per hour since 2007. That $7.25 is now worth less than $6.00 due to inflation. The fate of this provision remains uncertain. The House supports it, but a bipartisan group in the Senate has signaled its opposition. In this example, congressional inaction for over a decade effectively has cut the minimum wage by over 15% and will continue to chip away until a new law is passed. Scholars call this process “policy drift” and argue it has been central to shrinking the functional size of the social safety net since the 1980s.

Policy complexity, not gridlock

The point is that policy can change in many ways, like a house. Most visibly, you can demolish a house and rebuild it. Often this is impractical, and it’s easier to add a new room. Less visibly, you can remodel, converting a basement or garage without changing the house from the outside. Most subtly, changing circumstances can diminish a house’s usefulness, as when when a starter home fails to keep pace with the needs of a growing family.

Given these dynamics, myopically focusing on Congress and its purported gridlock mischaracterizes the real risk of legislative stalemate, which is not policy paralysis. It is shifting power to bureaucrats and judges, who are less publicly accountable and engage in more obscure and technical forms of policymaking.

After decades of financial decline, the media has fewer reporters who can untangle policy intricacies. It often exacerbates the problem by covering the conflict of the day rather than detailing the less provocative-looking silent progress of behind-the-scenes policy change.

Tracking the often subterranean ways that policy is actually made is admittedly difficult, but it is essential for both holding policymakers accountable and appreciating the political system’s true capacity for change.

[Understand key political developments, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s election newsletter.]![]()

Jeb Barnes, Professor of Political Science, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.