‘Subsidize the Truth about You’

“Every time I write a poem, I read it hearing your voice in my mind,” confesses Edoardo Ponti to David St. John. “And if it sounds like you could read it — that the words fit your vocal pattern — I keep it. You’re my aural litmus test of whether or not a poem works.”

More than two decades after he sat in St. John’s poetry-writing course as an undergraduate, Ponti eases into a booth at the Soho House in West Hollywood across from his former professor. The two immediately delve into a fascinating discussion about the lives they have since led as artists.

St. John, author of 11 volumes of poetry and University Professor of English and Comparative Literature at USC Dornsife, describes how he continually seeks to push the boundaries of his field by exploring the intersection of poetry, film and music. And this, Ponti observes, is exactly what has remained foundational to his own work as a film writer and director.

“I think I learned more about film from writing poetry,” said Ponti, who earned a bachelor’s in creative writing from USC Dornsife in 1994 and a master’s in film from the USC School of Cinematic Arts in 1998.

The son of actress Sophia Loren and the late producer Carlo Ponti Sr., Edoardo Ponti began his film career under the mentorship of Michelangelo Antonioni. Ponti’s films — including Human Voice (2014), The Nightshift Belongs to the Stars (2012) and Between Strangers (2002) — have been shown and honored at the Cannes, Venice, Tribeca and Toronto film festivals. In addition to his film work, he has written, produced and directed several stage plays as well as an opera.

In the following excerpts from their conversation, Ponti and St. John explore what it means to be a storyteller in the 21st century and what this requires of today’s rising talent.

Poetry and film

Edoardo Ponti: Since the time I was a student at USC, poetry has been so important to me, because it’s all about finding the core of things. It’s all about distillation; and film, too, is all about distillation. It’s the same thing. There’s simplicity to truth, and when truth becomes simple and immediate, it also becomes immediately personal and universal.

David St. John: That’s also one of the first things young poets need to learn and understand — that it’s all about the details. The films, poems, and stories we love most are often concerned with what is most intimate in our lives, and then what’s personal becomes universal.

EP: Another thing that poetry taught me — this is something that [Andrei] Tarkovsky also talks about and a little bit Roman Polanski — concerns the concept of time. That when you’re making almost anything, your musical piece or when you’re doing a performance or a film, your ally and your adversary is time. I can never dissociate myself from time.

DSJ: Well, time has only one message for us, and it’s that it continues and we do not. So, all art is necessarily about time. When I teach classes in poetry and cinema, I use Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time and Stalker, and I also use [Krzysztof] KieÅ›lowski’s The Double Life of Veronique and Blue.

EP: It’s also very much this liquidity of the rhythm — that each scene is a verse and each cut is a line break. It really is.

DSJ: When people ask me is poetry like painting, I tell them no, not so much anymore. The art form that contemporary poetry resembles most closely is cinema because it’s all about the movement of consciousness. It’s exactly that fluidity.

Choosing the life

EP: There is thinking about film as an audience member, and then there’s thinking about film as a filmmaker. I started thinking about film as a filmmaker through poetry — no question. When I decided to major in creative writing, the poetry track, I was following my instincts, and it was a very important thing.

DSJ: What’s so interesting is that you had that instinct in you and that this was your way to film. It’s so marvelous that you made that kind of recognition, even then at that age — that somehow poetry would be able way to give you a kind of armature within your filmic sensibility.

EP: I think people sometimes have this misconception that film is an end. Film is a means. Film is the pen. So I think the thing about film, for me at least, is to feed yourself and your persona with those ingredients that ultimately, when digested, can become a story.

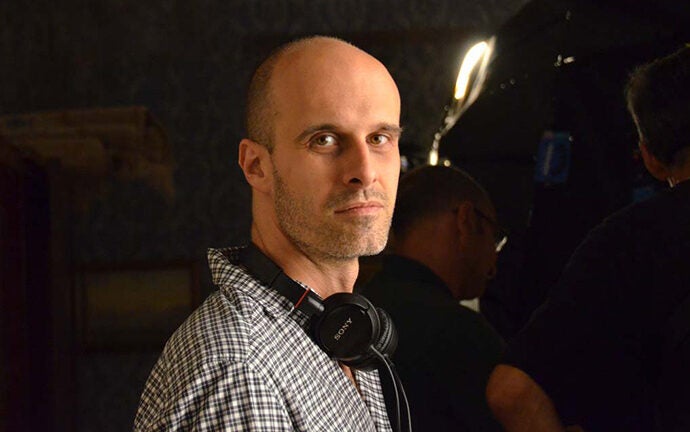

Alumnus Edoardo Ponti’s desire to make films springs from wanting to understand individual life journeys. “The script is a blueprint, not an end,” he said. “My job as a director is to take the script and to elevate what’s on the page, to make it real, and to give that reality a dimension that will speak to people.” Photo © Lauren Dukoff.

So my advice to young filmmakers is to learn about that — major in history, major in English, major in psychology. Then, once you start having a sense of who you are or you start asking the proper questions that would lead to who you are (because you know enough to ask the right questions), then maybe use film. But know that film is a pen. It’s an art in itself, but it’s an art of communication. It is not the end of it.

I think many people, many filmmakers, become too self-referential; they only watch movies, only refer to other movies. There’s a certain hollowness to what they do because their work is not informed by life; it is informed by other films.

What is more satisfying to me is to have movies that inform thoughts of life or what I’ve seen or what I’ve experienced in life.

DSJ: One of the things that’s so wonderful about what you’ve just said is that it reflects what we’ve been trying to do in the humanities at USC; we want to explain to our students that we in the humanities are the storytellers. My feeling has always been that, whether in history or in poetry, whether in psychology or philosophy, the humanities has always been where one learns how to tell one’s own story. We want to help students learn how to tell their own stories and to create that story, that narrative for themselves, along the way.

EP: Then, in poetry or film, one needs to sharpen the concept or the point of view. And tone, you know? The same story told through one point of view, through one tone, can become a drama or a social satire or a comedy. That’s really what living life gives you — because that point of view, that tone, is really your buried opinion.

DSJ: What I admire so much is that you’re describing what, in many ways, becomes the most difficult thing to explain to anyone who wants to be an artist. Whether one chooses cinema or poetry or dance or painting, those are just the choices of a medium. You may be better at one than another. But in fact, in some basic way, we’re all kind of doing the same thing. We try to bring a sensibility to the occasion, and to talk about the experiences and things that matter most to us.

University Professor of English and Comparative Literature David St. John taught Edoardo Ponti in his poetry-writing course at USC Dornsife in the early ’90s. “One of the things I’ve always loved about your poems is that they combine a kind of cinematic sweep in the language, but they are always psychologically acute,” St. John said. “That seems to me also a part of the film work that you’ve done; that is, how you’re always highly sensitive to the way your characters’ interiorities move against, or off of, or combine with each other.” Photo by Peter Zhaoyu Zhou.

EP: That’s right. And you know, it’s harder and harder in today’s society. I think success and fame lead us to want to tell a certain type of story. Some people have the good fortune of being honestly in sync with those kinds of stories. I don’t believe that somebody like James Cameron writes the stories he writes because he wants to make a billion dollars, but because he really likes to write those stories.

But I think if you’re not James Cameron — if you’re not in tune with those demographics or those masses — you have to have the courage to tell the stories that you need to tell and to find a way to tell them, and to find a way to navigate commerce and art.

DSJ: How have you done that?

EP: It’s very difficult, you know? I’m fortunate that my work takes me to other things. So I can do commercials and things that help financially. That’s what one has to do: find ways to subsidize the truth about you.

Storytelling through character

DSJ: One of the things I’ve always loved about your poems is that they combine a kind of cinematic sweep in the language, but they are always psychologically acute. That seems to me also a part of the film work that you’ve done; that is, how you’re always highly sensitive to the way your characters’ interiorities move against, or off of, or combine with each other.

EP: My desire to make movies has always been inspired by a deep curiosity about, and a desire to love, other people’s journeys. Whether I succeed most of the time or not, I don’t know, but I have a desire to understand them. I’ve always been fascinated by the looks people give, the pauses. That’s what has inspired stories for me more than events. It’s always been character-driven, rather than plot-driven.

The more mature I become as a filmmaker, the more successful I think I am at juggling those aspects. I think that, when you see my first movie, Between Strangers, there is a stubborn commitment to stay the course. And that creates a certain monochromatic emotionality to it. The older you get, the more you relax and the more you feel that people are more than one thing. They’re many, many, many things. It’s almost difficult to betray a character because people are capable of almost anything.

DSJ: Which experience teaches you.

EP: Yes. The only way that you can betray a character is actually through tone. If a scene tonally doesn’t feel right, it won’t be right. He wouldn’t do this, not because he wouldn’t do it, but because he wouldn’t do it that way.

The problem with movies is that the movie stays the same and you grow. You know, seeing my first film Between Strangers: I am still fond of it and respect it for what it is, but I have grown as a filmmaker. Audiences can enjoy it for what it is, but I see it for everything it’s not. Even with Human Voice, my most recent film. The other day I saw it, and it’s still relatively close to me, but there are things that I could see myself changing.

So, that’s the burden actually. That’s really the burden of what we do. We grow, but the work doesn’t grow with us.

Do you have that with the poetry that you’ve written?

DSJ: Absolutely. Even with “successful” poetry, right? After a time, you just have to make your peace with it. Again, for me it’s about a sense, a sensibility having changed.

Being ‘right enough’

DSJ: I love that idea of being able to fool oneself too soon that a work is “right enough.” I think maturity is not accepting right enough. When one is younger, one can be at a point where it seems urgent to hurry toward an acceptance of something in your work. In fact, what one learns is to always be suspicious of those motives and to think, “Well, no, maybe there is this other way.”

EP: Right enough also becomes wrong the older you get, because you’re running out of time. It’s as simple as that. You can only fool yourself for so many years. There’s a moment when, if there’s an inkling of integrity in your body, you need to be really honest.

On paper and on screen

EP: Making something cinematic really just means one thing. Images have a different weight on paper than when you execute them. It’s a different emotional weight. A smile can be a whole scene, if it’s captured correctly. When you’re writing a script, you have to be aware that everything can mean something. That is, if I put this prop down, it can mean something. If I write it in the script, it means that this has significance. If it doesn’t, I’m not going to write it.

The script is a blueprint, not an end. It’s a simple blueprint to what we’re going to do. My job as a director is to take the script and to elevate what’s on the page, to make it real, and to give that reality a dimension that will speak to people. And do that with the agreement and the understanding of the actors and how they contribute.

There are moments in The Nightshift Belongs to the Stars, with Nastassja Kinski, when she’s speaking to Julian Sands right before the big climb. Nastassja can, with one single look, convey a thousand things, which the script cannot. So, there’s also a question of how to give space to the actors and how they will fill in the gaps of the script. But in order to be able to fill in the gaps of the script, the gaps in a way have to be in the script.

Strengths and weaknesses

EP: There’s a sense in our society that we have to work on our weaknesses. I think we have to work on our strengths. If you’re not up to that, don’t try to do that, because there are people who are born to do that. What are you born to do? What movies are you born to do? Build on those.

DSJ: With young writers, we encourage them to read so broadly that they find writers in whose work they hear echoes of their own latent voices. It’s like looking into the mirror of language and beginning to understand what it is that belongs to you. You want to learn from other writers, but you don’t want to be that writer. You want to use them to discover what your own voice can be.

EP: I think it was T.S. Eliot who said, “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” Stealing just means making it your own — letting their work wash over you. Then, through the prism of yourself, how does this translate? Every poem, everything you read is, in a way, an act of courage. And by reading, a bit of that courage rubs off.

The craft and the life

EP: Something my father always said was “film is not an art.” For him art is something that is done by one person. We could debate why he’s wrong or right, but what’s interesting about this is that I’ve always approached film as a craft. Maybe one day, somebody will say this was artistic, but that’s not what I try to achieve. With a craft comes practice, with a craft comes discipline, and with a craft comes hours of just thinking. And the problem with being a writer is that most people in the house don’t know that you’re working all the time.

DSJ: You know, that’s an issue that is only slowly discovered by young writers, young filmmakers, young artists of any kind. What’s unknown to them is how much negotiating the details of one’s own life with the work you do becomes an important part of everything you are attempting. I vividly remember writing book reviews sitting in the front seat of a car at my daughter’s swim lessons. If you have a life and a family, you need to be able to carry that “motel” consciousness with you and work wherever you have the opportunity to work.

EP: That’s what being a professional means, right? You can switch on inspiration. You have a switch. You can’t wait for it. If you can only write between one and three and inspiration strikes at five, well then, you missed that train. So, you have to make it happen between one and three.

DSJ: It’s one of the things that I think isn’t talked about enough.

EP: Because it’s not very sexy, that’s why it’s not talked about.

DSJ: Writing during a child’s ballet lessons and swimming lessons is not very sexy. Yet that’s the power of the imagination. It doesn’t matter where you are, your imagination can put you where you need to be.

Responsibility to the audience

EP: Writing something that is layered and complex has its own set of responsibilities. By that I mean it is so easy to write something that nobody understands once you have the ambition. To write something that closely reflects who you are, you need to have the humility to express it as clearly as possible. That’s the hard part. Once you’ve accepted that this is your ambition, which is already difficult, you need to have the craft to express it.

For me, my desire to make Human Voice was really that. I remember finishing Nightshift and we had so much trouble with the weather and the continuity because, you know, weather changes six times a day in the mountains. So as a joke I said, “You know, I want my next movie to be set in one room, starring just one person and nothing else.” And it was Human Voice. The challenge of that was how do you let the audience in? On paper it feels like a great thing. But truthfully, after a few minutes a fear looms over you as a filmmaker — you don’t want the audience to be bored. How do you keep them engaged? And that’s when craft kicks in.

You have to shut out the world of the audience when you’re coming up with the idea. Yet once you’ve committed to the idea, you have to open the valve and let them in; then it becomes your job to express that idea as clearly as possible.

On authenticity

DSJ: If you could say something else to those students who care about having an inner life and care about making art, what would it be?

EP: I think it’s really, “Stop shadow-boxing with yourself.”

Learn to trust your instinct. Not everything has to be hard. If it comes out easily, it might be because it’s your inner voice speaking. So often we want to write because we want to emulate somebody we love, and we forget about ourselves in the process.

It’s also about patience. One step at a time. Something beautiful about making movies is not every shot needs to be a Rorschach. Most shots are about brick after brick, building that wall, that foundation, that house. Writing is the same thing. It’s a marathon; it’s not a sprint. We just have to enjoy it. It’s a combination of being demanding, but not so hard on yourself that you stop writing, that you stop creating.