6 reasons Shakespeare remains an icon 400 years after his death

“To be or not to be?”

That is the question — that has passed over the lips of countless actors playing Hamlet in the last four centuries on stage and on screen. It’s also a question that people in almost every country and in any language are familiar with. Playwright William Shakespeare’s reach is extensive.

This year, people around the world will be celebrating the Bard’s timeless works on the 400th anniversary of his death in April. There will be performances of his plays, readings of his poetry and new publications dedicated to analyzing his prolific and time-honored works.

So why exactly does Shakespeare’s work continue to resonate with each generation?

“Shakespeare reveals a different face to different cultures and different people at different times,” explained Bruce Smith, Dean’s Professor of English and professor of theatre at USC.

“When the First Folio of Shakespeare’s work was published in 1623, seven years after his death, Ben Johnson, who was a fellow writer, noted that Shakespeare was ‘not of an age, but for all time.’ That statement can be taken two ways: that the meaning of Shakespeare’s work is always the same or that it is always different. The second interpretation is the one that has been borne out.”

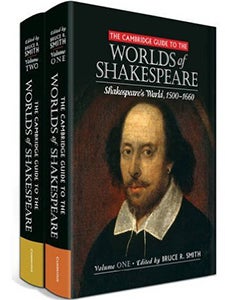

Smith is editor of The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare, which will be published on Feb. 11 by Cambridge University Press. Written for general and academic audiences by an international roster of almost 300 contributors, the guide boasts more than 2,000 pages exploring both Shakespeare’s world and the influence of his works on the world.

Topics range from the language and initial reception of Shakespeare’s plays and poems to studies of his works in popular culture, new media and advertising, as well as their influence on film, religion and fine arts.

Here are six reasons (among countless others) explored in the guide why Shakespeare remains an icon 400 years after his death.

1. You quote Shakespeare on a regular basis and you don’t even know it

Shakespeare’s influence on the English language runs deep. For instance, if you search the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) — the definitive record of the English language — Shakespeare is often identified as the sole user or first user of a word or phrase, according to Charlotte Brewer who authored the guide’s chapter on “Shakespeare and the OED.”

“The more of Shakespeare’s words you look up, the more you discover that, time after time, according to the OED, he turns out to have used language in wholly individual ways or (more often) to have originated usages that subsequently became established in the language,” Brewer wrote.

If you have ever said “It’s Greek to me,” suffered from “green-eyed jealousy,” “stood on ceremony,” been “tongue-tied,” “hoodwinked” or “in a pickle,” you are quoting Shakespeare.

2. The Bard’s reach is cosmic

The planet Uranus has 27 moons, the majority of which are named for Shakespearean characters: Titania, Oberon, Puck (A Midsummer Night’s Dream); Ariel, Miranda, Caliban, Sycorax, Prospero, Setebos, Stephano, Trinculo, Francisco, Ferdinand (The Tempest); Cordelia (King Lear); Ophelia (Hamlet); Bianca (The Taming of the Shrew); Cressida (Troilus and Cressida); Desdemona (Othello); Juliet, Mab (Romeo and Juliet); Portia (The Merchant of Venice); Rosalind (As You Like It); Margaret (Much Ado About Nothing); Perdita (The Winter’s Tale); and Cupid (Timon of Athens). (The two remaining moons, Umbriel and Belinda, are named for characters in Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock.)

3. Some people don’t believe Shakespeare wrote the plays and poems that bear his name

What cements a writer’s legacy more than when a segment of their audience contests their work? The great Shakespeare authorship controversy was sparked in the 1850s — more than 200 years after his death — when American writer Delia Bacon and British bookseller William Henry Smith each published their arguments on the topic. Among other potential authors of the plays credited to Shakespeare, they suggested philosopher Francis Bacon and poet Walter Raleigh were more likely the “real” writers of Romeo and Juliet, et cetera. In the subsequent century, more than 50 alternative writers were proposed.

However, David Kathman, who wrote the “Authorship Controversy” chapter in The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare, is confident that Shakespeare’s works are his own. He explains: “Despite the claims of anti-Stratfordians, the evidence that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works of William Shakespeare is abundant and wide-ranging for the time, more abundant than the comparable evidence for most other of his contemporary playwrights.”

Kathman is one of several independent scholars without an academic appointment recognized as authorities on Shakespeare who contributed to the guide. Smith noted that their inclusion “is yet another sign of Shakespeare’s universal appeal.”

4. Shakespeare has been a profitable brand for hundreds of years

In 1710, publisher Jacob Tonson started a trend when he adopted Shakespeare’s likeness as his corporate logo, using the Bard’s portrait on his bookshop sign, in advertisements and on the editions of Shakespeare’s works that he published. In the past four centuries, Shakespeare’s strength as a brand has not faltered. In fact, it’s ubiquitous. His likeness and his works have been used to sell soap, chocolate, cigarettes, computers, beer, soda and almost anything else you can think of.

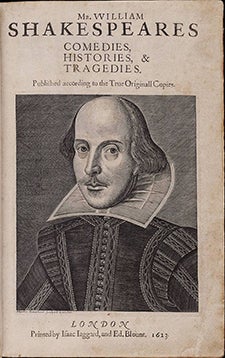

5. His likeness remains a mystery

Although Shakespeare’s image has been reproduced time and again, we don’t actually know what he really looks like. None of the printed portraits that accompanied his work date back to his lifetime. The image that most people are familiar with is an engraving by Martin Droeshout, which debuted in 1623 on the title page of the first edition of Shakespeare’s collected plays called the First Folio.

However, Erin C. Blake explained in the guide’s chapter on “Likenesses: Prints and Portraits,” that the editors of the First Folio were friends and colleagues of the Bard’s. She wrote: “They knew what he looked like and would not have accepted a portrait that differed wildly from the man they remembered.”

6. His works are universal and enduring, and so are his characters

Shakespeare’s works are emotional, hilarious, pithy. But above all, he was masterful at imbuing his stories and his characters with qualities that audiences and readers identify with — Hamlet’s anguish, Ophelia’s distress, the enduring love between Romeo and Juliet.

In Samuel Johnson’s preface to The Plays of Shakespeare (1765), he wrote: “His characters…are the genuine progeny of common humanity, such as the world will always supply, and observation will always find.”

For those who would like to explore Shakespeare’s legacy further, the print version of The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare will be available at the USC Doheny Memorial Library. The online version of the guide will be accessible through USC Libraries in the coming months.

Smith will be further celebrating the anniversary of Shakespeare’s passing with the publication of his seventh book in June: Shakespeare | Cut: Rethinking Cutwork in an Age of Distraction (Oxford University Press). Shakespeare | Cut, which looks at the creative ways snippets of the Bard’s work have appeared on stage, in videogames or on YouTube, is an elaboration of the Oxford Wells Shakespeare Lectures that he delivered at Oxford University in 2014.