Upstream and Downstream

A slew of news stories renewed discussion about gender-based violence in the past year. From sexual assaults on college campuses to the NFL’s reaction to domestic violence, those stories suggest there is plenty of work to be done in shifting our culture’s views on women — and the perspectives of boys and men in particular.

Fortunately, there is an ongoing legacy of men involved in preventing violence against women, going back to the 1970s, said Michael Messner, professor of sociology and gender studies.

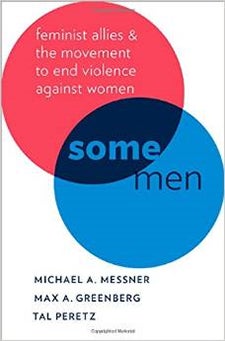

Messner and USC Dornsife doctoral students Max Greenberg and Tal Peretz have written Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women (Oxford University Press, 2015), a contemporary history of men working with the women’s movement, exploring their motivations and strategies to prevent gender-based violence.

Messner and his co-authors interviewed activists ranging in age from 22 to 70, charting the development of feminism over 40 years from street-based political action to grant-funded institutions. In the process, they have documented how racial diversity has been introduced to the field, along with a growing focus on how violence affects victims of all genders.

Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women is a contemporary history of the male activists working with the women’s movement.

Male activists learned from feminist women that the best way to help was to reach out to other men, Messner said.

“The language of upstream and downstream developed,” he explained. “Women were saying, ‘We’re doing all this work downstream with the effects of violence. We need people to do work upstream to prevent the causes of violence.’ ”

Messner began interviewing pro-feminist men in the late ’70s. At the time, groups such as the Bay Area’s Men Against Sexist Violence were passionate about civil rights and anti-war activism, and they saw the fight against gender-based violence as an important step in that work. Like many of the women drawn to early feminism, they also felt choked or disenfranchised by the restrictive gender mores of the time.

One unexpected revelation from the book’s research is the disparate profile of these men. The activists Messner was first inspired to interview were white, educated and predominantly Jewish, reflecting that community’s concern for social justice. The men typically discovered feminism through women’s political activism on college campuses and in communities.

Book authors Tal Peretz, Michael Messner and Max Greenberg, from left. Photo courtesy of Michael Messner.

Often, they were also witnesses to violence against mothers, sisters or girlfriends while growing up. Fathers or stepfathers sometimes directed that violence against them as boys.

Today, there are grant-funded outreach organizations introducing a younger generation to violence prevention, often reaching into black and Latino communities. That work ties into outreach to gang members, at-risk youth and even prison populations. It acknowledges that stopping gender-based violence often means ending behavior that affects boys as much as women.

“With an influx of men of color, we’re getting a deeper understanding of how violence against women connects to other forms of institutional violence,” Messner said. “It’s very interesting when you look at what’s going on with violence against black men by police. When the men we interviewed say to young black and Latino guys, ‘You need to not hit women,’ the guys say, ‘You should see what the cops do to us.’ ”

While millennials might be adopting what sociologist Joe Reger calls “fluoride feminism” — cultural ideals passively absorbed, rather than consciously chosen — the book highlights how much work there is to be done.

Messner stressed that anti-rape and anti-domestic violence organizations have been made sustainable through foundation and state funding, but have softened the political activism that once shook up larger institutions.

“The risk today,” Messner said, “is that professionalized violence-prevention becomes a pragmatic effort to stop a single behavior — akin to stopping smoking — rather than a movement that addresses violence as part of a larger effort to create a more equal and just society.”

Overall, Messner is heartened by the progress that has been made. Working on a history of the men within the movement allowed him to reconnect with contacts who were personally inspirational to him. But it also let him meet younger men who are continuing their work.

“If you look at anti-violence work as an individual, you might see it as tilting against windmills because there’s so much violence in the world,” he said. “And yet there’s this whole community of people who feel that they’re a solution to that.”